America's Most Memorable Zionist Leaders

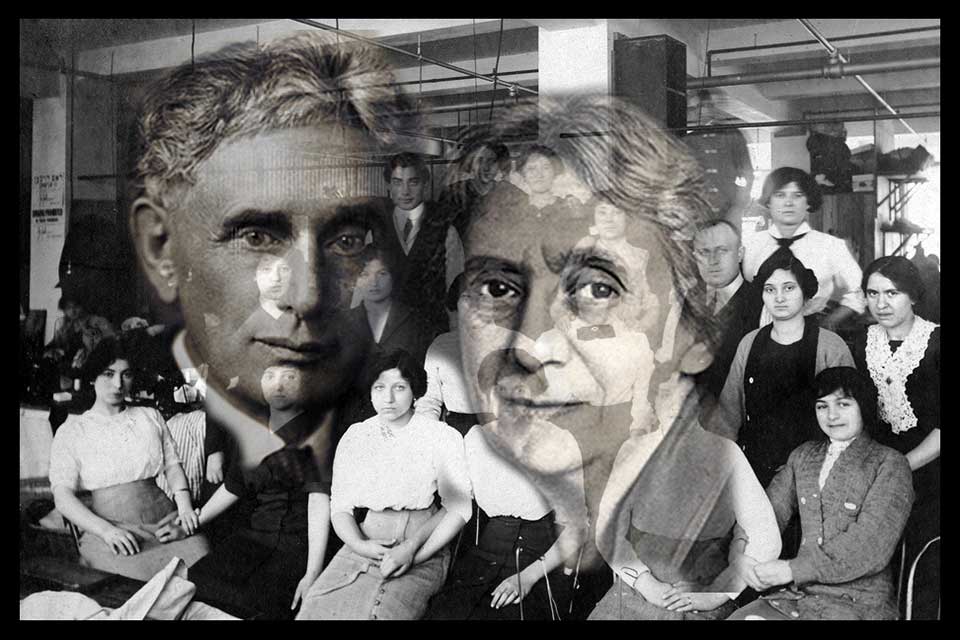

Louis Brandeis (above left) and Henrietta Szold (above right) became role models for American Jews, says Professor Jonathan D. Sarna.

Louis Brandeis (above left) and Henrietta Szold (above right) became role models for American Jews, says Professor Jonathan D. Sarna.

The Individual in History: Essays in Honor of Jehuda Reinharz

The question of what makes a successful Jewish leader has many answers, none of them simple.

Individual leaders develop within a complex context of socio-political circumstances of period and place. They are transformed by circumstances, responding and reacting in ways unique to the individual, and subsequently transforming those same circumstances in a process of change and development that is mutually reinforcing and non-linear.

The life journey of Jehuda Reinharz, president of Brandeis University for 17 consecutive years, provides an intriguing example of how effective Jewish leadership can develop.

The life journey of Jehuda Reinharz, president of Brandeis University for 17 consecutive years, provides an intriguing example of how effective Jewish leadership can develop.

The new book "The Individual in History: Essays in Honor of Jehuda Reinharz" (eds. ChaeRan Y. Freeze, Sylvia Fuks Fried and Eugene R. Sheppard; 2015) begins with an overview of Jehuda Reinharz's life story and continues with essays on topics he held keen interest in and to which he devoted scholarly attention.

The book, organized into five parts and 39 essays, begins with the story of Reinharz as an Israeli teenager in his new home in Essen, Germany, where he and his family had just moved. It was at the Humboldt Gymnasium which Reinharz attended, like his father before him, where he "first experienced the sharp sting of antisemitism."

The turning point came for Reinharz when he determined to refute the opinion of his "history teacher's claim that the imputed criminality of the Nazis was overblown for after all, 'only three and a half million Jews' died during World War II."

Refuting his teacher meant conducting research at a time in the late 1950s when little had yet been published on the subject of the Holocaust. Undaunted, Reinharz sought the advice of the cultural advisor to the Central Council of Jews in Germany who shared with him what he had, brochures and pamphlets, and "referred him to the work of a number of scholars in Israel."

The dearth of material about the Holocaust and Reinharz’s determined position to counter his history teacher's antisemitic statements propelled Reinharz into active participation in the Zionist youth movement in Germany and a lifelong course of academic scholarship.

Key themes in Reinharz's extensive scholarship include Jewish emancipation, antisemitism and Zionism. As such, essays in the book are organized under the titles Ideology and Politics; Statecraft; Intellectual, Social and Cultural Spheres; Witnessing History; and In the Academy.

In conjunction with the Tauber Institute at Brandeis University's September 2015 launch of the new book, the Hornstein Jewish Professional Leadership Program shares excerpts here of the ninth essay by Hornstein Professor Jonathan D. Sarna, "America's Most Memorable Zionist Leaders."

Excerpts from "America's Most Memorable Zionist Leaders"

by Jonathan D. Sarna

Louis D. Brandeis, outstanding Harvard-trained Boston lawyer, leader of the American Zionist movement, and the first Jew to be nominated to the Supreme Court of the United States.

Louis D. Brandeis, outstanding Harvard-trained Boston lawyer, leader of the American Zionist movement, and the first Jew to be nominated to the Supreme Court of the United States.

Henrietta Szold, exceptional Jewish thought-leader, writer and editor, co-founder of Hadassah and "Mother of Israel" for her dedication to service and social justice.

Henrietta Szold, exceptional Jewish thought-leader, writer and editor, co-founder of Hadassah and "Mother of Israel" for her dedication to service and social justice.

-

"Jewish Literacy," a widely distributed volume by Joseph Telushkin that promises "the most important things to know about the Jewish religion, its people and its history," highlights two American Zionists as worthy of being remembered by every literate Jew: Louis Brandeis and Henrietta Szold... They have been the subject of more published biographies than any other American Zionists, and they dominate children's textbook presentations of American Zionism as well. They are, in short, the best-known American Zionists by far.

-

Scholars may lament that other critical figures — people such as Harry Friedenwald, Israel Friedlaender, Richard Gottheil, Hayim Greenberg, Louis Lipsky, Julian Mack, Emanuel Neumann, Alice Seligsberg, Marie Syrkin and so many others — have not achieved immortality in this way. Stephen S. Wise, Abba Hillel Silver and Mordecai Kaplan may have come close, but they are neither as well-known as Brandeis and Szold nor as universally respected. Kaplan, moreover, is far better known as the founder of Reconstructionism. Whether others deserve greater recognition, however, is not the question to be considered here. That would demand an extensive inquiry into what "greatness" in Zionism entails and how it should be measured. Instead, our question is why Brandeis and Szold achieved special "canonical status" among American Zionist leaders, while so many others did not.

-

Existing studies of American Zionist leadership fail to consider this question. Taking their cue from social scientific studies of leadership, they focus instead on the sources from which Zionist leaders drew their authority, the strategies that they pursued, and the extent to which they preserved tradition or promoted change. Yonathan Shapiro's well-known volume entitled "Leadership of the American Zionist Organization, 1897–1930" (1971), for example, follows Kurt Lewin in distinguishing between leaders from the center (such as Louis Lipsky) and leaders from the periphery (such as Louis Brandeis) and analyzes differences between the backgrounds, styles and leadership methods of different American Zionist leaders. But questions of long-term reputation and popular memory — why, in our case, Brandeis and Szold won historical immortality while so many others were forgotten — go unanswered.

-

Here, I shall argue that the historical reputation of Brandeis and Szold rests upon factors that reach beyond the usual concerns of leadership studies. How they became leaders and what they accomplished during their lifetimes is certainly important, but even more important is the fact that both Brandeis and Szold became role models for American Jews: they embodied values that American Jews admired and sought to project, even if they did not always uphold them themselves. Brandeis and Szold thus came to symbolize the 20th-century American Jewish community's ideal of what a man and a woman should be. Their enduring reputations reveal, in the final analysis, as much about American Jews as about them.

In his essay, Sarna continues to outline the lives and accomplishments of Louis Brandeis and Henrietta Szold: Brandeis as outstanding Harvard-trained Boston lawyer, leader of the American Zionist movement and the first Jew to be nominated to the Supreme Court of the United States; and Szold as exceptional Jewish thought-leader, writer and editor, co-founder of Hadassah and "Mother of Israel" for her dedication to service and social justice.

-

All of these accomplishments surely earned Brandeis and Szold the accolades showered upon them, but they still leave open the question of why others, who also achieved a great deal, in the course of time have been totally forgotten. Why, in other words, has popular memory operated so selectively in the case of America's Zionist leadership, to the advantage of Brandeis and Szold and the disadvantage of everybody else? No definitive answer to this question is possible, but five factors stressed by the biographers of Brandeis and Szold seem particularly revealing. At the very least, they help to explain why the lives of these two Zionist leaders took on special relevance to subsequent generations of Jews.

Sarna goes on to describe these five factors, and concludes:

-

In an era when many doubted the ability of American Jews to negotiate both sides of their hyphenated identity, Szold and Brandeis served as prominent counterexamples. They provided reassuring evidence that the ideal of inclusiveness could be realized, and that Judaism, Zionism and Americanism all could be happily synthesized. For this, as much as for their more tangible organizational contributions, American Jews revered them and remembered them.

Dr. Jonathan Sarna is the Joseph H. and Belle R. Braun Professor of American Jewish History at Brandeis University, chair of the Hornstein Jewish Professional Leadership Program, chief historian of the National Museum of American Jewish History and president of the Association for Jewish Studies.

Last update: August 25, 2015

Jehuda Reinharz was born Aug. 1, 1944, in Haifa to German Jewish parents who had immigrated in the 1930s to Palestine with their respective families. When efforts to immigrate to the United States failed, the family moved back to Germany in 1958 — back to his father’s hometown of Essen. In 1961, the peripatetic Reinharz family moved to the United States and settled in Newark, New Jersey, where the high school senior met his future wife Shulamit Reinharz, who was born in Amsterdam. Upon graduating from high school, Reinharz studied Jewish and European history at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, where he earned his BRE, and Columbia University where he earned his bachelor of science.

Jehuda Reinharz was born Aug. 1, 1944, in Haifa to German Jewish parents who had immigrated in the 1930s to Palestine with their respective families. When efforts to immigrate to the United States failed, the family moved back to Germany in 1958 — back to his father’s hometown of Essen. In 1961, the peripatetic Reinharz family moved to the United States and settled in Newark, New Jersey, where the high school senior met his future wife Shulamit Reinharz, who was born in Amsterdam. Upon graduating from high school, Reinharz studied Jewish and European history at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, where he earned his BRE, and Columbia University where he earned his bachelor of science.