Artist Spotlight: Mea Lath

Photo Credit: Toni Shapiro-Phim

Birds, Teachers, and Community and Culture in the aftermath of genocide

By Toni Shapiro-Phim, Program in Peacebuilding and the Arts

Renowned Cambodian American rapper praCh Ly has written and directed a performance piece that shines a light on experiences of Cambodian American communities through instrumental music, song, and dance. KHMERASPORA premiered in April of this year in Long Beach, California, which is home to the largest community of Cambodians outside of Southeast Asia. Most Cambodians there arrived as refugees in the aftermath of a genocide in the 1970s, followed by a decade of violent conflict when many ran for safety and sustenance to refugee camps along Cambodia’s western border with Thailand. More than 100,000 Cambodian refugees settled in the United States in the 1980s and early 1990s, most in California.

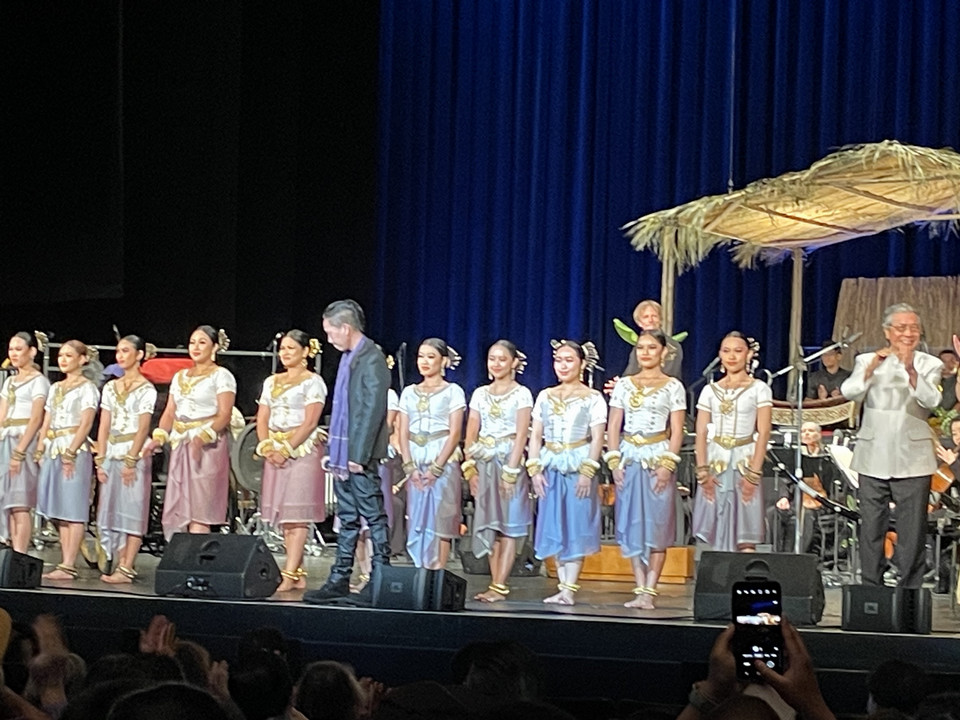

praCH Ly took on a daunting task this year: sharing elements of what it means to survive violence, displacement and loss on a grand scale, and then to re-create community and culture on the other side of the world. A collaboration between Long Beach Symphony members, under the baton of music director Eckart Preu, and singers, dancers, and Cambodian pin peat musicians (the pin peat ensemble accompanies classical dance, shadow puppetry and Buddhist ceremonies), this event under praCH Ly’s direction included three world premieres by internationally-celebrated Cambodian composer Dr. Chinary Ung. I attended the show whose two performances (in a venue seating 3,000) were presented to a full house each time. I had a chance to speak with one of the artists central to the production -- Mea Lath, choreographer and performer of Khmer (Cambodian) classical dance -- about this artistic endeavor, and the communities for which it was created.

January 2024 will mark the 45th anniversary of the end of the genocide in Cambodia. During the almost-four years under Khmer Rouge rule, from 1975-1979, between a quarter and a third of Cambodia’s entire population perished from starvation, disease, overwork, torture and execution. As we see the world over, an end to mass violence can, at the same time, be just the beginning of legacies of the torment and trauma and physical harm produced by that very violence. Life in refugee camps – in a war zone – on the Thai-Cambodian border was precarious, too. praCH Ly, Chinary Ung, Mea Lath and their collaborators face this inheritance head on in KHMERASPORA, through rap and other songs, western classical and pin peat music, and Cambodian classical dance, while also acknowledging, honoring and indeed demonstrating the beauty, dignity and brilliance that Cambodians have brought, and will continue to bring, to their new home. The centrality of cultural expression in creating meaning and cultivating a renewed sense of community and of possibility, despite the shattering of so much that people hold dear, comes to the fore, both in the production of KHMERASPORA, and in the lived experience of Mea Lath.

“Last year Bong [“older brother”] praCH, the person who wrote and directed the show, reached out to me and told me he’s doing this collaboration and he gave me free reign to choreograph whatever I wanted,” Mea Lath began. “Initially it was just going to be three minutes long. And even if only three minutes, I was like, whoa, that's long, because I had only choreographed something like a 30-second piece for a song. Lok Kru [“teacher”] Chinary and I started discussing what our vision was. And so, because the theme was the Cambodian American experience, a big part of my experience is, you know, being a dancer and learning so much about my culture and identity through dance. I also wanted to incorporate major milestones in my life. So, for instance, I've been to Cambodia three times. The first time was to train with Neak Kru [“teacher”] Sophiline [Cheam Shapiro] and then it wasn't till my last trip [in 2019], my third trip, when I finally got to go to Siem Reap to see [the temple complex of] Angkor Wat. Just seeing the top of the Lotus Towers peeking out from the forest was something really spectacular. I still get emotional thinking about it because, you know, we've always, I've always seen images of Angkor and how beautiful it is. But to witness it in person was just indescribable.”

Mea spoke to me about how upon arriving in Cambodia for the first time – she had been born in a refugee camp on the Thai-Cambodian border – she experienced culture shock in various ways in the capital city of Phnom Penh. But when she approached Angkor Wat on that trip in late 2019, something shifted. “I felt I was home.”

“That's why I wanted to choreograph my piece honoring or paying homage to Angkor Wat,” she continued. “Because before I stepped near or I saw Angkor Wat… I want to say, I've never really felt good or worthy or, you know, like valuable for who I was. And seeing Angkor Wat was proof, tangible proof of what our ancestors left for us. And that greatness is really in our blood. I would hope that more Cambodians from the diaspora would get to see it and visit and experience those same feelings.

“Why I chose [to choreograph the dancers as] birds is because dance, and my teachers, really gave me the wings to soar and explore the world. Because if it wasn't for them, I think I would have stayed in the toxic environments that I grew up in [in Long Beach]. But, because of the performances, [dance] took me everywhere – to universities, to all of these beautiful venues, showing me that there's more than my immediate surroundings at the time. Because I owe so much of who I am to the arts and to my teachers, I do feel a sense of duty to also pass it on to my students. My students are Cambodian Americans, most of them are now mixed race and their parents are of a generation that is very disconnected from their culture. And for a lot of my students, their first introduction to Khmer culture, their first exposure is in my class. So, the piece is also dedicated to them.”

Mea Lath adjusting the posture of a young dancer in Long Beach. Photo by Phillip Nguyen

On stage in KHMERASPORA, the dancers/birds open their cloth wings, taking some inspiration from a classical dance, Robam Preap, in which dancers represent doves. Mea utilized specific Khmer dance positions that signify flight including one in which dancers balance on one leg, the other lifted to the back, and bent, with the sole of the foot facing skyward. As for the costumes, she scoured Los Angeles’ fashion district.

“At the end [of my piece] the birds are forming the shape of Angkor Wat and so I wanted to choose a color for the costumes that was similar to the sandstone, but not dull because it has to shine on stage. So, I found this bluish iridescent color that in certain lighting reflects different colors. I think I must have remembered the sky at Angkor being like that blue-pink color, because I actually ran out of the blue material and had to go shopping a second time. And then I found the pinkish color that I ended up wearing with two other two birds. So, it just kind of fell together.” Her ultimate goal was “to transport the audience to the majestic feeling of Angkor, but in the 21st century. And I wanted the audience to feel light, and I wanted their hearts and souls to flutter.”

How was it to work with award-winning artists, I asked her.

“This was the very first time that I performed with Bong praCH and Lok Kru Chinary and the other featured artists. It was really an honor because Lok Kru Chinary has worked with my teachers and, even though I've never worked with them, I knew of Bong Kalean Ung [actress and singer] and Chrysanthe Tan [violinist]. I knew of their work; they’re just amazing. And then it was really nice to discover Kaitlyn Mady [flutist]. She's so young, and I was drawn to her, naturally.

“I started to choreograph knowing which melody [from the Cambodian pin peat ensemble repertoire] Lok Kru Chinary would use for the entrance and that he was going to incorporate part of the original Robam Preap melody. One challenge for me was to speak the same language as a professional composer! I had to figure out how to explain myself. And I didn’t know how both ensembles [the pin peat and the symphony] would sound together. But Lok Kru Chinary sent me a mock-up and hummed the tune. And our rehearsals went well.

“At the end of the day, I'm just one of many Cambodian dancers of the diaspora, and Bong praCH could have chosen anyone. And he chose to trust me. He gave me full control of what to do. So that was cool. I said yes to his invitation, because I'm always looking for a challenge. One of the things that I've been trying to figure out is how to make Cambodian dance cool so that it's relevant and attractive to the younger generation. In order for us to preserve and keep this in our community, we have to pass it down. And in my experience so far, my students eventually move on in life. I haven't yet found an apprentice. So that kind of makes me worried. I want to adapt Khmer dance a little, I guess, for the modern world. I knew this collaboration would be something to help guide that.

Mea Lath performing "Blessing Dance" at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Asian Art, Washington, DC. Photo by Glenn Clabough

“I came up with the name Modern Apsara Company for my own dance ensemble because of my history and the work that I’ve done in the community. People have referred to me as the modern day apsara. And so, I thought this was a fitting name, because traditionally apsaras are only seen to be beautiful celestial beings. [Countless images of apsaras are carved on the walls of Angkor Wat and other ancient temples.] But, when you really look into who the apsara represents, she has this powerful intelligence. And just like today's Cambodian women, we're not the traditional, submissive, quiet women. We have voices. We have great ideas. And we have more of a standing here, or at least in today's world. So, my company is also dedicated to all the modern apsaras in the world.

“I moved to the United States [from a refugee camp] in 1992. Like a lot of Cambodians, I grew up in a rough neighborhood, on government assistance. And at the time I didn't realize or recognize, I guess, that my parents were experiencing PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder]. And so, I had to grow up very early. I really don't remember being a child at all. I unfortunately witnessed a lot of violence -- domestic violence, gambling, you know, being around neighbors that had gang members in their family.

“When I was 12, things got really bad and my parents were separating and divorcing and what was really hurtful was that when my mother decided to be on her own, her community, her friends, turned their back on her. Some people even tried to talk her into staying because being a single mother would mean that my brother would join a gang and my sister and I would [soon] be pregnant. So, when she met Neak Kru Sophiline [the dance teacher], she saw a woman who’s really strong and independent and graceful. And because she feared for our future, she wanted to put me and my sister under Neak Kru Sophiline’s guidance, to learn from her because she was afraid that she wouldn't be able to raise us properly by herself as a young single mother. At the same age as she was at that time, I don't know how I would have done it, really! I don't have any children now, and I'm just barely able to support myself. So, when I was 12, I enrolled in dance.

Neak Kru (Teacher) Sophiline Cheam Shapiro correcting Mea Lath's posture in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Photo by Srey Leak Rin

“I do consider both of my dance teachers as motherly figures. Neak Kru Sophiline planted my seed. And Neak Kru Charya [Burt] also, of course, another mother figure. I think she was the one who really watered and nurtured me and I say this because I didn't get to spend that much time with Neak Kru Sophiline before she moved back to Cambodia. I think they are both the most brilliant, creative people in the world. Because of those relationships I also felt the pressure of choreographing this piece: I didn't want it to look mediocre or silly as that would reflect on them. I’m so glad it came together beautifully.”