An Artist at ICAF: Interview with Samwel Japhet Silas

By Toni Shapiro-Phim, Co-director of Brandeis University’s Program in Peacebuilding and the Arts

Still images from Zoom interview with Samwel Japhet Silas

Still images from Zoom interview with Samwel Japhet Silas

We met at ICAF in Rotterdam. What brought you there this year?

My company was invited to perform our piece ‘Onyesha Thamani,’ which means Showing Value. It was a duet reflecting on gender equality here in Tanzania, and as a global issue. It was created using dance-theatre as a language to reflect on this issue in the city we are living in, Dar es Salaam. At ICAF I did it as a duet with my colleague Irene Themistocles Ruyakingira. We performed twice. My company is called Nantea Dance Company. The company provides multifaceted performances and community-based projects, and hopes to contribute to the promotion and development of the dance scene in Tanzania, inspiring youth to become ambassadors of development and social change. ‘Nantea’ reflects the idea of being pulled towards something or someone, in a positive way. When you’re falling in love with someone, you are drawn into someone or something, just as you might be drawn into dance, into the arts.

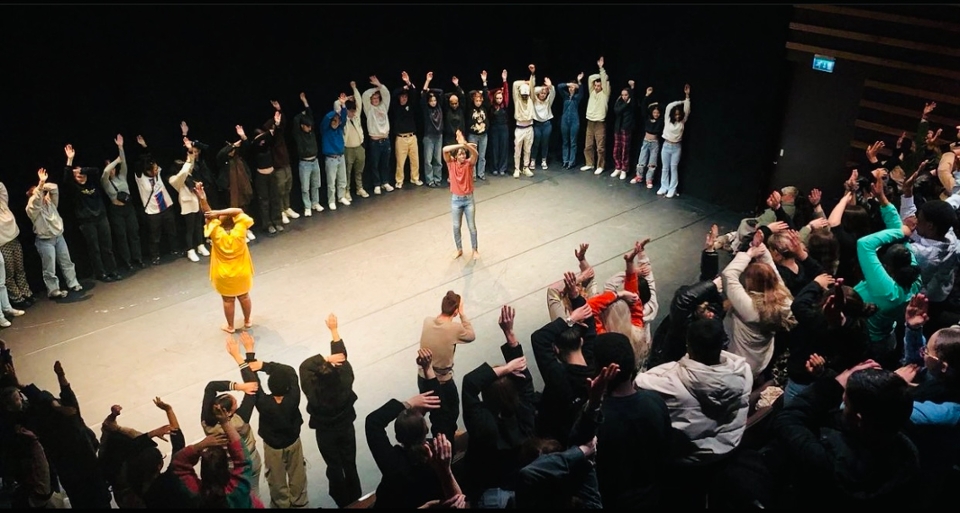

At ICAF, I opened the show by inviting people to join us on stage. At first I was standing on stage with a microphone. ‘How would you feel being in a community where people do not see you?’ I asked the audience. They answered that they would feel sad, feel terrible. So I said we feel sad and we feel terrible. We traveled all the way from Tanzania to Rotterdam and here you are just sitting and staring at us, expecting us to dance for you. And we can’t see you. I said, ‘Unfortunately, we didn’t come here to dance for you, to perform for you. But what I can say is that we came here to speak with you, to reflect with you, and to resonate with you.' Because, the essence of the festival is bringing people together to share. I often feel, even when I go to the theater, that there is a disconnect between what is happening on stage and the audience. Of course, you can see from afar. But it’s different when you are close. You can see the sweat, the exhaustion, the emotions, and hear the breathing. Then it is easy for you to interact and reflect. Once they [members of the audience] were all sitting in a circle on the stage, we performed our piece.

Performance of Onyesha Thamani, International Community Arts Festival, Rotterdam, 2023

Performance of Onyesha Thamani, International Community Arts Festival, Rotterdam, 2023

Would you tell us about the dance you performed?

I came up with the concept and choreographed Onyesha Thamani. It was first done in Dar es Salaam in 2021, and performed in almost 10 different public spaces. My company did this in collaboration with the all-female dance group Girls Power; the dancer with me at ICAF is from that company.

I decided on the topic of gender equality because, first, it is something very much significant to me. I ran away from home when I was around five-six-seven years old as a result of child abuse. I recognized abuse that others were experiencing, given my life history. I wanted to do something; I wanted to respond to it. I don’t want to just sit and observe. It drives me to want to say something, to reflect something; to bring people together so they can talk and reflect, using dance as a language. In the performances in Dar, we had a lot of exchange, a lot of Q & A sessions afterwards, where people were asking questions. We were also asking questions. So, it’s like opening an environment where people can share their thoughts about this issue, and what is their take-away from the performance, and what are they going to do.

It was a time [during the pandemic] when we were getting news from many places that people were experiencing [increased levels of] domestic violence, both kids and especially women. It’s also a global issue as well, not only about Tanzania. [In Tanzania] the system is very much in favor of men, much more than women. Women are seen as human beings just supporting men. Men are doing all the decision-making, taking all the big initiatives. Women have always been on the side. But it is interesting that now we have a woman president and seeing that shift is very exciting. Although I see the change is not so genuine from the men who are in power, it’s beautiful to see that women, young women and even some men, are inspired by her. I’m also very much inspired by her.

In a video montage of performances of Onyesha Thamani in Dar es Salaam, we see audience members in market places, at bus stops, and other public spaces watching, and then speaking with the performers. Would you explain your approach to audience engagement?

Onyesha Thamani, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Photo by Jimmy Mathias – Nantea Dance Company, 2021

Onyesha Thamani, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Photo by Jimmy Mathias – Nantea Dance Company, 2021

After every performance we engage the audience by doing a movement with the audience and describing it. We’ve asked the audience questions and they’ve always had many questions for us. We are trying to interact with people from all different places, as they come and go. People are there from different parts of the city. Discussions happened mainly after the show. Sometimes we would sit down; sometimes we would stand there while exchanging. We also shared really personal experiences from the women in the female dance group. For example, two of them were explaining about their personal experiences. It was so interesting to hear people reflecting on that and being present in asking questions and receiving what we were saying. The issues are complex. Some people are asking, ‘What can I do if my neighbor is beating his wife?’ I then asked, ‘What will you do if you see someone beating your child in front of you?’ They answered, ‘I will try to stop them.’ There are many ways to try to stop them. Go there yourself. Go to the police. It was beautiful to hear these kinds of questions and comments.

Here in Tanzania, especially in the health sector, there are not many safe spaces for them to go. People just end up dealing with the violence themselves. When they ask, often, we say they could go to a hospital for example, with a certain government-funded section or office which supports community-based issues, like marriage problems, or child-parent issues.

What shifts in questions or attitudes have you seen over time, if any, since you began presenting this dance?

Back in 2016 we did a project in the central part of Tanzania – Iringa – outside of city centers, with the Gibney Dance Company of New York. This was a project of Muda Africa (Tanzania) and Gibney Dance (USA) in collaboration with Engender Health, funded by the U.S. State Department. It was part of the annual “16 days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence.” We did that project there for five days, performing in schools and public spaces. The main questions at that time were – Ok. We know this thing is happening, every day, but how can we get out of this as a community, as a country? We got in very long discussions. Many people were saying we need to have platforms where people can freely talk about these things. This is a starting point to build a community in which we live peacefully. It’s been seven or eight years since then. A lot of things are changing. Many people are speaking out, in the digital world. Now it is very different compared to what it was like seven years ago. Now people share a lot. Somehow [not only] bringing awareness, but at the same time, the person who is doing violence is feeling shame. So, he wants to change the way he treats other people. And Onyesha Thamani reinforces the importance of this, highlighting how critical it is to value one another, as well as oneself.

Where did inspiration for the movements and choreography of Onyesha Thamani come from?

Onyesha Thamani, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Photo by Jimmy Mathias – Nantea Dance Company, 2021

Onyesha Thamani, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Photo by Jimmy Mathias – Nantea Dance Company, 2021

First, in Tanzania, I’m considered a contemporary artist. I say that what I do now is dance-movement, which is inspired by many things – traditional dances and music, contemporary language, visual arts, and by realities and situations that happen within our societies. I don’t say I’m a contemporary dancer. I don’t describe my dance as contemporary dance, but it’s an easy way to understand it. This language is very new to people. What I wanted to do is to make a language that people can easily interact with. We added some key words [through gesture and movement] in this choreography and then after the show we would demonstrate some of those keywords. This means violence; this means chaos; this means taking action. My colleagues and I created those movements because we knew this kind of dance was very new. Like signature movements that are easy to interact with. It was then easy to open a discussion.

We worked with a colleague who is a music producer, Shabani Mugado, to record a soundtrack. In the music there are a lot of words in Swahili. This is another easy way to interact with the audience.

What was your first encounter with dance?

I have a long story. While on the street I found other street kids. We used to do all kinds of things together, including stealing. When I was living on the street, it was very much just being in the moment. I even changed my name. I told myself I would never go back home. I thought it was better on the streets than going back home. I’ve seen other kids on the streets – when things are tough, when it is raining a lot, some go home. That was never an option for me.

For four or five years I was part of an organization working with youth and kids living on the street. That organization, Makini, taught traditional dance, acrobatics, acting, drawing. But I had no interest at first. They would collect us and take us to cultural centers, to go to swim, to have lunch, these kinds of things. After those activities we would go back to the streets. Eventually I joined a three-year dance program at Muda Africa, a dance center. They rented a room for us – we were sharing, almost four or five of us. In 2015, I got an opportunity to go to Nairobi for three months for a creative economy course at the GoDown Art Centre. When I was there, I got money and used it to get my own place when I returned to Tanzania.

On your website you note that your background influences your current work. Would you elaborate on the ways it continues to influence you?

In many ways my dance-theatre work is influenced by how I grew up. I see the world in my own way. Also, for instance, some of the issues I like to explore through my work relate to personal experiences or community-based issues. Somehow, they constantly come back to me. When I see injustice happening, it drives me crazy. I remember one time in one show, a new production we premiered in March called ‘HUMAN: Life in a rapidly changing world,’ a friend told me, ‘The street is talking through you.’ [laughs] The ways I see the community and the justice system and all the violent systems -- they keep coming back when I hear stories of people experiencing abuse. Somehow it creates an urge for me to do something about it and dance is the language I use to express that.

ICAF is a community arts festival. How do you define your community or communities?

It starts with the people I am very close with, and expands to their friends and their friends, and their neighbors and everyone I meet in the streets. Just imagine, from the moment you wake up, you are meeting so many people in the street. We are very much being influenced going from home to work; without even talking to them you’ve exchanged something with 50 people. Very much we are being influenced by almost everyone. I buy food from someone I don’t know. I am influenced by that food; that exchange. I buy water from someone I don’t know. Somehow, I feel that there’s a lot of trust in that exchange. Something I can’t catch, I can’t expect it, but it’s there.

I don’t know if you know this concept of Ubuntu, which is like ‘I am so you are,’ [a person is a person through other people]. Like people are greeting people that they don’t know. You can start a discussion, you can start an argument with someone you don’t know. Just in public busses you can sit and people can start talking about football, can start talking about anything and they can start laughing [as if] they have known each other but they don’t know each other. So I can see a big sense of community without even us being in control of it. It’s there, you know. If it’s not there it means you have just excluded yourself from it because it is there. That’s why I wanted to do the piece at ICAF to invite people to sit with us on the stage because it is easier for people to connect with us that way. That concept of Ubuntu is changing with globalization, digitization. People would rather talk online than talk like this. The effect it leaves behind is more disconnection between people. That’s the sad part. But dancing in public spaces, or surrounded by an audience on a stage, counters that.

Onyesha Thamani,Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Photo by Jimmy Mathias – Nantea Dance Company, 2021

Onyesha Thamani,Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Photo by Jimmy Mathias – Nantea Dance Company, 2021