The Premiere of A Deepest Blue – a Reflection

By Kalie Jamieson, PhD candidate in Cultural Anthropology, Brandeis University

On the evening of April 18, my partner and I crowded into the Laurie Theater at Brandeis University with numerous others – students, faculty, community members – to witness the premiere of A Deepest Blue by Cambodian dancer Prumsodun (Prum) Ok and Japanese musicians Ota Yutaka, Venerable Nuiya Toshiya, Kunimoto Yoshie, and Otonashi Fumiya.

In the car ride over, my partner asked what kind of show this was to be; I was unable to provide an answer. Though a dancer myself, I was not familiar with classical Khmer dancing. I had briefly discussed classical Khmer dance with my advisor, and the organizer of the event, Toni Shapiro-Phim – she told me that Khmer classical dance was traditionally performed by women, how it told the stories of the gods, and how it was deeply intertwined with spirituality. We compared it to our own artform of ballet as both require strenuous, strict training to perfect the delicate, precise movements and body placements. Toni also told me about Prum and how he was among the few men to perform roles usually reserved for women in this style of dance, how he started his own company of gay male dancers, and how having queer people perform this technique was a way of insisting on their place in the heavenly stories as well. Yet, beyond this baseline, I was going into A Deepest Blue with no idea of what I might encounter.

The performance that unfolded that evening was beyond anything I could have imagined. As someone who deeply believes in the power of dance and performance to tell stories, convey complex emotions, and to connect a group of people in time and space, this piece impacted me intimately. It lingered, and lingers still, in my mind and heart.

* * *

A Deepest Blue opens with a blank white stage and blue background. Prum stands on the white platform center stage. I feel that he is standing on the edge – of a body of water? of life? of the world? It is unclear. He begins to move slowly, almost imperceptibly. I watch with bated breath and can sense that the rest of the audience is doing the same. We cannot look away. Prum begins to make his way down the steps as if he is stepping into water, testing the temperature, the strength of the waves. I can see his foot and leg muscles flex as he stands seemingly motionless and can practically feel the muscles screaming against the stillness as he peels his foot off the ground one metatarsal at a time. As he sways ever so slightly, I can almost see the waves crashing up against him. Though his arms are open slightly, his movements, posture, and expression suggest he is succumbing to the water, rather than welcoming it. I suddenly realize he is crying. Sobbing. His abs tighten as his body is wracked with sobs. He walks deeper and deeper into the imaginary water. The stage goes dark.

Prumsodun Ok, A Deepest Blue, Laurie Theater, Brandeis University, 2024. Photo by Ethan Hortelano

Prumsodun Ok, A Deepest Blue, Laurie Theater, Brandeis University, 2024. Photo by Ethan Hortelano

When the lights return, they are blue, making the floor, the backdrop, Prum, all appear blue. He is under the water now. His movements are slow and weightless, flowing with an ease that only comes when one has given up. The stage goes dark again.

When it lights back up, it is bathed in a yellow white light. Prum is curled in a ball on the ground downstage. Three of the musicians, dressed all in white, begin to glide onto the stage in slow, matched steps, while the Venerable Nuiya Toshiya takes his place by the drum and begins to strike it with a slow rhythmic beat. The other musicians take turns playing their instruments, one after the other, over and over. They walk around Prum, as if they are a part of him or a part of the ocean into which he has sunk. The sound is beautiful but haunting. I am tense in my seat, uncertain and fearful. The musicians begin to add in dance steps, their circular arm and leg movements similar to the ones Prum performed moments before. Then, all at once, they lightly stamp a foot on the ground, and he responds by slowly pushing himself up, fingers flexed away from the ground. He wipes water, sand, or sleep from his eyes and turns to take in the musicians. He gestures towards them with delicately flexed hands. As the musicians walk away from him and toward the drum, he rises to his knees and faces the audience. Bringing his thumbs to his forehead, hands above, he bows ever so slightly. I feel a shift coming. Toni tells me later – this is when he begins to truly dance in the classical Khmer style.

Prumsodun Ok, Otonashi Fumiya (left), Kunimoto Yoshie, Ota Yutaka, and Venerable Nuiya Toshiya (rear), A Deepest Blue, Laurie Theater, Brandeis University, 2024. Photo by Ethan Hortelano

Prumsodun Ok, Otonashi Fumiya (left), Kunimoto Yoshie, Ota Yutaka, and Venerable Nuiya Toshiya (rear), A Deepest Blue, Laurie Theater, Brandeis University, 2024. Photo by Ethan Hortelano

He sways on his knees, stretching out flexed hands as if testing the water. Then he stands, moving to balance on one foot, posing, and shifting to another balance. Though posed, he is not stagnant. You can feel the movement, the breath, the energy flow within and beyond him continuously. I find myself enraptured by the placement of his fingers and hands, so beautifully elongated and stretched. As he moves about the stage, his center of gravity remains low to the ground; his head stays on the same level. Only when he shifts to balance, pose, or shift weight does he change levels. Now, his face looks peaceful, matching the feeling of his movements. As the musicians sit and play, he seems to be exploring the ocean, or the depths of whatever he stepped off into. It’s as though he has made peace with whatever was causing him to sob, but the feeling is not one of hope. Rather, he has made peace with existing on the bottom of the ocean.

And then the trash begins floating in. Tied to thin sticks held by two student performers, trash infiltrates the ocean/stage from all sides. At first, Prum ignores it, continuing his dance while it floats around him. It comes close to him without overtaking him. He returns to the center of the stage to continue dancing and now he sees it. He dances oriented towards the trash rather than the audience, his face solemn. Gracefully, yet severely, he pushes the trash off stage with a hand placed triumphantly on his hip. With his back to the audience, he returns to center stage once again.

Yet his strife is far from over, his ocean/mind far from clean. In comes the oil. The student dancers bring in bucket after bucket of thick blue-black paint, splattering the crisp white floor like inky blood. Prum turns towards us, and I feel my stomach tighten. He is covered in “oil,” his face is covered, his torso is covered. The paint is slippery. He maintains his posture, but his feet are not rooted as they were before; there is nothing to grip, to hold on to. The student dancers return carrying a large net. They creep up on him, capturing him in the net as slowly as his movement progresses. He wraps the net around him at first, almost as if it is welcome. But the dancers push him down and force him to become entangled. They drag him around the stage, his struggling body making the task difficult. The oil smears around the stage as Prum thrashes in the net, crying out. He is fighting - for life? for freedom? His cries are real, weeping, scared. I feel it in my throat. Then, just as suddenly as they appeared, the dancers leave, abandoning him tangled and weeping. Mangled.

Prumsodun Ok, A Deepest Blue, Laurie Theater, Brandeis University 2024. Photo by Ethan Hortelano

Prumsodun Ok, A Deepest Blue, Laurie Theater, Brandeis University 2024. Photo by Ethan Hortelano

Students Micah Heilbron (left) and Maya Becker approach Prumsodun Ok with a net, A Deepest Blue, Laurie Theater, Brandeis University 2024. Photo by Ethan Hortelano

Students Micah Heilbron (left) and Maya Becker approach Prumsodun Ok with a net, A Deepest Blue, Laurie Theater, Brandeis University 2024. Photo by Ethan Hortelano

Prumsodun Ok struggling to break free of the net, A Deepest Blue, Laurie Theater, Brandeis University 2024. Photo by Ethan Hortelano

Prumsodun Ok struggling to break free of the net, A Deepest Blue, Laurie Theater, Brandeis University 2024. Photo by Ethan Hortelano

The stage is dark. It is dark for a long time. Prum’s presence is revealed only through his crying. My eyes search for him in the dark – Has he gotten free? Can he stand? Is the oil in his eyes, his nose, his throat?

When the stage finally lights again, the musicians move to encircle him once more. Words – inspired by Buddhist teachings– scroll across the backdrop. Though these are unfamiliar to me, I am left with the message that all life is intertwined and all life is sacred. The words tell Prum not to give up, not to cease seeing value in himself because the life in him is the life in the trees, the mountains, the ocean. Venerable Nuiya Toshiya, a Buddhist monk, begins to chant low and steady. He shows Prum a compact mirror, which Toni later tells me signifies him telling Prum to recognize his own value. The musicians cover him in lipstick and red flower petals, a stark and lively contrast to the blue-black oil.

They move to the platform and resume playing their instruments, not to the audience, but to Prum. He raises his hands to his forehead as he did before he began dancing the classical Khmer dance. He stands, his body covered in blue-black and red, and dances oriented towards the musicians. Then he turns and addresses us once again. The monk continues to chant while Prum dances. The stage is darker than before, and his face is harder to read. However, he conveys more through the rest of his body. The drum and Prum pick up speed and urgency. He takes up more of the stage and performs with a different kind of fervor. Toni later informs me that he drifts away from the strict classical technique here, as he innovates the traditional form in his own way.

This segment of the performance is intense; everyone is locked into him. He seems to sense it. At times, he stops moving all together and faces the audience, making eye contact and holding it fiercely. He seems to be searching for someone or something. Other times, he moves almost frantically, allowing his body to be overtaken by the movement. He slips in the paint and falls often. At first, when he falls, he does not stand up right away. However, as the dance continues, his time spent accepting the fall shortens. Soon, each fall is met with an instant attempt to re-stand, the oil threatening to pull him back down and hold him down. Yet, he fights against it. At one point, he faces an old Cambodian man in the audience, who meets his stare then minutely bows to him with his hands pressed against his forehead. The moment, almost unnoticeable, brings tears to my eyes, which I quickly blink back so as not to miss any of Prum’s dance. Afterwards, I realize this man was one of the artists who survived the genocide and helped reinstate dance and music in Cambodia after it was safe to once again. Within that context, his bow to Prum seems like a blessing, an acknowledgement of passing on the torch, so to speak.

Eventually, the drum slows, and Prum slows to match it. His abs tense as they did at the start of the show, but this time it’s from exertion of movement rather than tears. He walks to the front of the stage, and the musicians stop and turn to leave, blue footprints left in their wake. The lights go out.

Prum is back on the platform as he was at the very beginning. He is a changed man. Not just because he’s covered in paint and lipstick, his hair ruffled. His whole being is changed. He holds his arms up beside him, higher than before. The lighting casts a shadow on the background behind him that looks like a cross. He steps off the platform and into the imaginary water as slowly and delicately as before, yet this time he seems to welcome it, seems to greet it as a friend. He cries. But the tears do not feel distraught, hopeless; they feel cathartic, changed.

Prumsodun Ok, A Deepest Blue, Laurie Theater, Brandeis University 2024. Photo by Ethan Hortelano

Prumsodun Ok, A Deepest Blue, Laurie Theater, Brandeis University 2024. Photo by Ethan Hortelano

* * *

After witnessing A Deepest Blue, I am changed. My partner and I leave the theater, turning the performance over and over again. We both felt that the ocean was meant to symbolize the ocean – its power, immense beauty and life, the harm and hardships humans have brought to it, its ability to restore life. Yet it seemed to symbolize something more, something internal as well. The ocean also felt like the depths of Prum’s mind and soul.

In the talk after the show, Prum shared that traditionally, the role of the classical Khmer dancer was to pray for life and therefore ensure it – a “heavy responsibility.” The piece was deeply inspired by his own life, his own struggles. He explained that he had been doing the work of an entire company by himself, as well as carrying on the tradition of the dance and caring for his country. It all felt too heavy, and so he closed his company. Yet rather than bringing relief, the closure only added to his pain for he felt as though he failed “[his] teacher, [his] tradition, [his] motherland.”

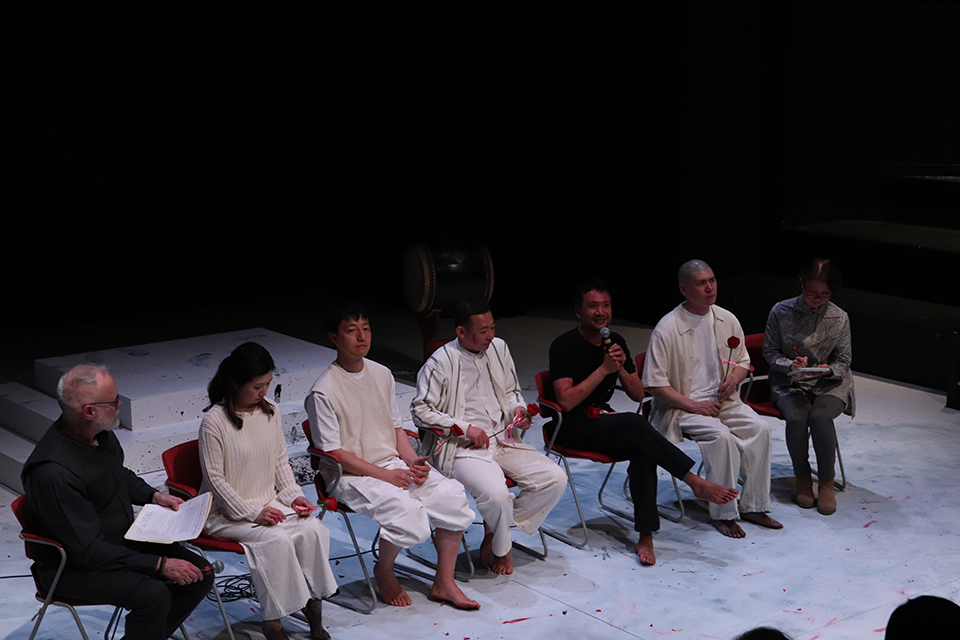

Q & A with audience following the performance of A Deepest Blue, Laurie Theater, Brandeis University 2024, featuring Professor Tom King (moderator), Kunimoto Yoshie, Otonashi Fumiya, Ota Yutaka, Prumsodun Ok, Venerable Nuiya Toshiya and Naoko Goldstein (translator). Photo by Ethan Hortelano

Q & A with audience following the performance of A Deepest Blue, Laurie Theater, Brandeis University 2024, featuring Professor Tom King (moderator), Kunimoto Yoshie, Otonashi Fumiya, Ota Yutaka, Prumsodun Ok, Venerable Nuiya Toshiya and Naoko Goldstein (translator). Photo by Ethan Hortelano

In the audience, there was a husband and wife, musician and dancer, who had been professional artists before the genocide, survived it, and helped bring the art back to life afterwards – the husband was the old man who bowed to Prum. One of the women from the first post-genocide cohort of dancers was also present. Prum described his dancing, and the musicians’ styles, as both deeply rooted in their traditions and wildly experimental. This seemed to be reflected in the joining of artists, old and young, traditional and “experimental,” in that theater.

Though Prum’s performance shifted away from the tradition of classical Khmer dance at times, its legacy lived through his movements, his fingers, his ribcage. As he transcended the boundaries of the tradition, he danced on the boundaries of spirituality and performance, of earthly and spiritual existence.

A Deepest Blue was presented by the Global Community Engagement Program of the Samuels Center for Community Partnerships and Civic Transformation (COMPACT) at Brandeis University, and co-sponsored by the Theater Department and the Creativity, the Arts, and Social Transformation (CAST) minor. This production was made possible by the New England Foundation for the Arts’ National Dance Project, with lead funding from the Doris Duke Foundation and the Mellon Foundation, and received additional support from the Hewlett 50 Arts Commissions, Creative Capital, Kenneth Rainin Foundation, MAP Fund, and the National Endowment for the Arts.