Shutting Mouths: A Composition of Silenced Voices

by Wai Hin Ko Ko, Ph.D. student, University of California, Berkeley

All internet networks across Myanmar were abruptly cut when I woke—strangely—at 4 a.m. MMT (UTC+6:30) on February 1st, 2021. Burmese people living abroad began to worry about their families inside the country—and vice versa. Myanmar was blinded and unheard. In the days that followed, the streets of Yangon and other major cities began to fill—slowly at first, then swelling—as news spread that the military had detained the entire recently-elected government and declared a coup on state television, the only source of information in those early hours.

The Uprising

Home Wi-Fi networks became a fragile thread of hope for those on the streets, supporting their freedom of expression. One by one, houses along the roads removed their passwords—this was how people in Myanmar fought to access reliable information. The politicians and public voices who might have led the people were blindfolded, silenced, and detained. Yet, thanks to the bold voices of celebrities—like actor Daung, singer Phyu Phyu Kyaw Thein, and model Myat Noe Aye—the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) slowly came to life.

A vocalist friend of mine was detained—but I didn’t hear the news until much later, while I was in the Philippines preparing for my U.S. student visa, shortly after receiving news of my acceptance into the Ph.D. composition program at the University of California, Berkeley—a moment that should have marked a new beginning. After returning to my hometown to spend time with my family before leaving for the U.S., a group of police stormed into my room without a warrant. They forcefully arrested me and confiscated everything: my audio station, computer, speakers, and hard drives. Nothing was left. Not even a sound. Through a bribe, I was released and eventually allowed to leave the country.

Shutting people’s mouths and blinding their eyes—that is the very first act of any dictatorship.

From Silence to Sound

As a Burmese composer in the diaspora, I was compelled to create art about censorship when sincere voices—innocent young students who boldly spoke out on the streets—were silenced by deadly, blood-shedding gunfire. When two people—one a hip-hop artist, the other a political activist—were sentenced to death by hanging, the burning in my heart reached its peak. From that fire—of grief, fury, and helplessness—Shutting Mouths (ဝဇီချုပ်), my composition, was born as a sonic refusal to forget.

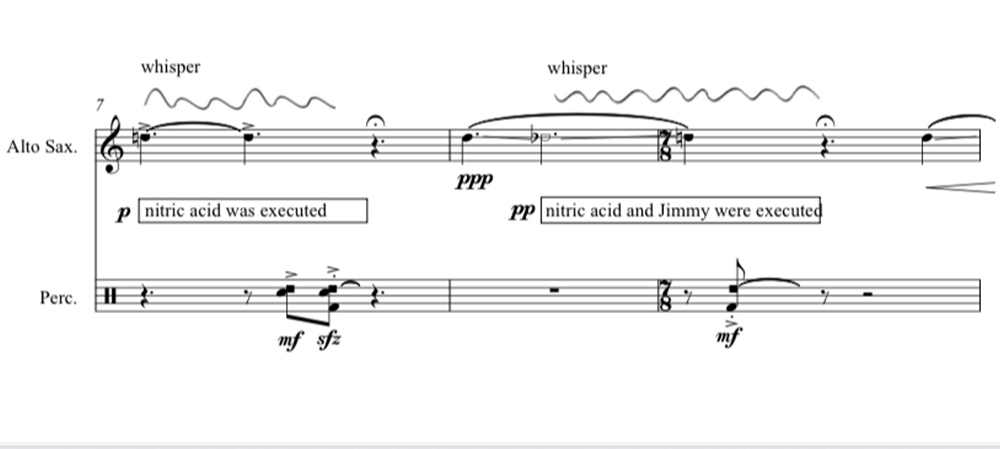

Shutting Mouths is written for alto saxophone and a set of percussion. The saxophone, often associated with bold, lyrical expression, is pushed to its limits—through overblown air, broken phrases, and muted tones. The percussion does not accompany—it interrupts, suppresses, and overwhelms. Their interaction becomes a struggle between voice and force, expression and control.

The piece begins with the saxophonist playing long, breath-laden tones while quietly calling the names of the two martyrs—those sentenced to hang. Their names are barely audible, hidden beneath the sound, as if whispered through a locked throat. This opening is not just musical; it is ritual and remembrance. The air itself becomes unstable, trembling between speech and suppression.

Suddenly, gunshot-like drum strokes cut through the air—violent and abrupt. They silence the saxophone’s fragile breath. A metal chain is spread across the surface of a tom [drum]. When struck, the rattle of the chain evokes the sound of both violence and captivity. It doesn’t just echo gunfire—it lands with the weight of the innocent being detained.

The long notes of the saxophone begin to shorten, its phrases shrinking. The dynamics grow softer, more hesitant—until the percussion overwhelms it completely. The articulations follow a fading sequence: short staccato, then slap tongue, followed by key clicks, and finally just air noise. Each gesture is softer than the last, gradually erasing the saxophone’s voice. Yet the disjunct rhythm of these movements makes the performer appear active, even as their sound disappears beneath the percussion.

The Sound of Resistance

Then, the piece shifts into a new texture—uneasy, fractured, overwhelmed. It is no longer a dialogue, but a collapsing space where sound is buried under pressure. Most of the rhythmic figures in the piece revolve around groupings of two and three—echoing the dual memory of Jimmy and Zay Yar Thaw, the two martyrs whose presence the music seeks to embody. Their presence is embedded not only in voice, but in the pulse of the music itself.

In the latter section, the saxophonist is left with nothing but long breaths blown into the air column—no pitch, just the sound of breath. Meanwhile, the percussionist gently jingles the chain. The breath noise grows into something more—an exhausted, fearful breath that feels almost human. The percussionist lifts the chain into the air and continues to activate it softly, letting it shimmer above the silence like a suspended threat.

As the piece continues, the saxophonist speaks a short Burmese poem into the air column of the instrument—barely voiced, fragile, blending breath and language. The percussionist responds, not with words, but with sound—gently echoing through the chain’s subtle movements. It is not a resolution, but a moment of resistance carved into the noise.

As the piece moves toward its end, silence stretches wider between each sound. The air becomes heavier. In the final breath of the saxophonist—nothing more than a whisper of air—the percussionist lifts the chain and places it around his own neck. The gesture is quiet, but devastating. It needs no volume to speak. It is a symbolic act of shared captivity, of bearing the weight of the silenced. The voice is unheard, yet still there—buried, trembling, resisting. This is what censorship feels like. It is a silence that screams.

A Composer’s Reflection

As a composer in exile, I often ask myself: What is the use of music when people are dying? When voices are erased, and even breath becomes dangerous? Shutting Mouths was not an answer—but it was the only response I could offer. I could not speak back to the generals. I could not march beside those I love. But I could shape sound into remembrance—into a trace of the voices that once filled the streets.

This piece is not only about censorship. It is about presence—the kind that refuses to vanish. Even in silence, the voice remains. Even when buried, it breathes. I do not know if my music can bring change. But I know it can remember. “Shutting mouths” is never just censorship—it is the first movement of dictatorship, and too often, its soundtrack.