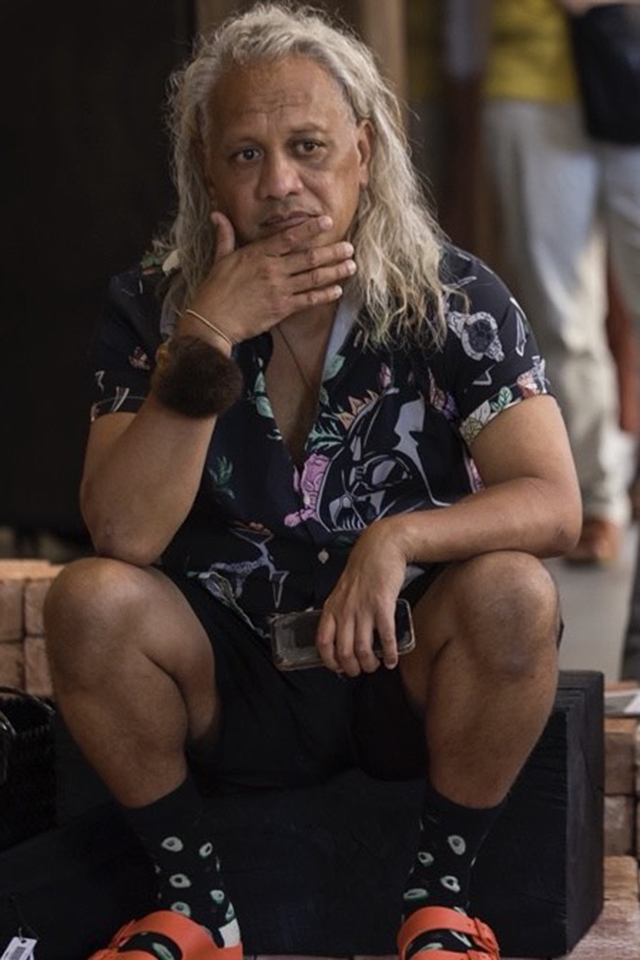

Artist Spotlight - Tiaki Kerei

Photo Credit: Anna Kucera; copyright Tiaki Kerei

In conversation with Toni Shapiro-Phim, PhD, Director of the Program in Peacebuilding and the Arts, Brandeis University

Earlier this year, in a segment on New Zealand’s 1 News entitled “Why I’m Reclaiming An Indigenous Name,” journalist Te Ahipourewa Forbes noted that award-winning dancer Tiaki Kerei “was born Jackie Gray, named after his late father. But his journey toward his Māori identity led him to embrace his father’s Māori name, not just in tribute, but as a way to strengthen and revive his own sense of self. ‘It just occurred to me that my father's ingoa in Te Reo Tiaki Kerei would be an important step to revitalise myself… It helped me get through some rough times, it helped me deal with some mamae (hurt) that was intergenerational and... it's almost like I feel a korowai (cloak) around my shoulders,”’ Tiaki shared.

Toni Shapiro-Phim of Brandeis’ Program in Peacebuilding and the Arts had the opportunity to interview Tiaki Kerei as well, just a week before this newsletter was set to be sent out. Toni and Tiaki had first met at the “Dancing Ecologies in the Asia-Pacific: Negotiating Identities in a Context of Change and Dispossession” conference in Singapore in 2024. This recent conversation focuses on Tiaki’s commitment to well-being and creativity in today’s Aotearoa New Zealand. Excerpts from his stories, all in his words, follow.

On His Embodied Research Lab

The Embodied Research Lab came out of an offer of a residency at The Auckland Performing Arts Centre, and it was a pretty unique premise. The organization had received funding to support Māori and Pacific artists at their venue by giving them free space. One of the people in the administration there had seen my Instagram posts about me and my mum and the rehabilitation journey with my mum's stroke recovery, and how movement was such a critical part of this daily practice that I would do with my mother. Because I couldn't really leave mum, initially, at that time, I would just go outside and dance on the way to the park, or I would dance in the street. I would dance at the bus stop, and I would post these daily things of my need for creativity as restoration and self-healing. The Performing Arts Centre’s administrator saw that and went, “Hey, I think you should come to our studio and do your practice here.” So that's how the Embodied Research Lab began. I went in, and with South African dancer Celeste Dillon, the primary focus is really on what are the priorities in terms of sustaining a physical practice as we age. We discovered that meeting weekly, we would really have a lot to share that we had encountered. There was a lot going on politically.

Tiaki Kerei and dance partner Celeste Dillon; photo by David St. George; copyright Tiaki Kerei

Tiaki Kerei and dance partner Celeste Dillon; photo by David St. George; copyright Tiaki Kerei

At the end of last year, there were lots of protests, including marches, around standing up for the Treaty of Waitangi, which is our constitutional declaration of partnership between Māori and the government that was at risk of changing through new legislation. Ultimately, we stopped it. [During that time] we would meet sort of like for a coffee date, starting out by talking about what’s going on, but end up dancing. Then we would video these sessions, and then we took some time and ultimately wove them together and performed it as a work. I guess, in many ways, the Research Lab is similar to social media, but just for the body, yeah, where you're like, This is how I feel today. This is what I ate today. This is who I'm seeing today. This is where I've been just recently. And your body holds that knowledge, and you're capturing these kinds of slices of life, and we're developing what that means as our own kinetic narrative. Those slices of life are in your body and between bodies, and a way of physically processing [what is going on].

We had [the studio space] for five months till the end of the year, and then we did a performance. And then they got back in touch and said, “Hey, you know what, we'd like to continue the relationship. Would you like to continue the relationship?” And I said, Yes, of course, because who knows what we're aiming for, and who knows what the point of it is, except that it's about collaboration, and we're collaborating on the possibility of something coming from the space.

On Being Māori

I am Māori [through] my ancestry on both of my parents’ sides. That is my cultural heritage, and I have tribal affiliations: Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāpuhi, Te Rarawa. The Māori worldview principally centers itself on belief systems that are sacred and spiritual, and the key foundation of that is our understanding of the relationship between earth and sky as beings. So Ranginui is the Sky Father, Papatuanuku is the Earth Mother. And from their love and their embrace [came] the Atua, who are the, I guess the phrase would be “forces of nature.” Other people could use the words gods, deities, that kind of thing. They become the natural world energies. The ocean is Tangaroa, the forest is Tāne-mahuta. So we use these Atua to embody different aspects of nature. There are stories between those gods that we honor or acknowledge. And there's this other principle idea, which is that we say all things come from absolute nothing or potential, which is called Te Kore. Then the next phase of expansion is through Te Po – the night. And it's a long night. And Te Ao, the world, which is daylight, is the result. I guess we're oscillating all the time, thinking about the gestation of ideas. We're a very conceptual culture, and so that's why I'm also starting to realize that being Māori and being creative is one and the same thing. I don't need to be a “Māori creative,” because being Māori is [being] creative.

Whakamana Creatives

I'm a director of the collective, Whakamana Creatives, with co-founder Mitra Khaleghian. Whakamana is a Māori word that means to empower and to support the things that give you pride, the things that give you presence, the things that are inherently your foundational roots and values. The name Whakamana Creatives is a call to action to support creatives in the endeavors of life, beyond just the premise of performance, but also in terms of being human beings that have a conscious and subconscious relationship to expression that seeks to shine a light into a part of your identity, and part of global conversations of peace, justice, and transformation. So with that being said, yeah, my background is in contemporary dance, but my present moment is around physical, mental, and spiritual well-being, which I think is a lot more applicable to all peoples, [and it] is something that I'm interested in continuing to facilitate.

Whakamana Creatives gather at the beautiful Ellen Melville Centre, in its Pioneer Women's Hall in the middle of Auckland. The Centre works with different groups. It could be rehabilitation groups; groups dealing with violence; pride groups. Lots of different people use that space.. The person in charge of programming said it feels really good to have people with kaupapa, Māori customary practice (skills; knowledge; purpose), who are singing and chanting and learning and praying, thinking about the Atua, thinking about the contemporary issues facing everyone, thinking through interculturalism, and what that means as New Zealanders. I’m not just centered on Māori people, but inclusive of all New Zealanders, understanding a Māori worldview being something that actually helps us with a global worldview.

It's been this incredible fast-track journey which feels a lot more organic than most other ideas of companies and organizations that do the strategic thinking, and then create the activities. We did the opposite. We do all the things that mean something to us, and then we evaluate them, and then we realize that there's something to pursue.

One of the participants (who then became the producer for Whakamana Creatives), Mitra Khaleghian, whose parents had immigrated to New Zealand from Iran, worked in war zones for about 20 years in Afghanistan, Ukraine, Zambia, and other places. And she would often comment to me that what we were exploring in these community sessions had a major relationship to peacebuilding experiences that she had been a part of.

Because of her work in war zones, I feel like I've finally met someone with that appetite for how dance can often feel like a war zone, and how difficult it is to sustain yourself. And then sometimes how alienating it can be as a contemporary dancer to acknowledge your heritage, but in ways that are not traditional. And so that's kind of what I mean by feeling a sense of diaspora within your own identity and in your own realms. But, as I say, the dance pieces that you make use the tools related to understanding an interpretation of the cosmology and of the value system as a way forward, as a way to exist in this unique paradigm that none of our ancestors would have anticipated.

Initially there was an open call to join Whakamana Creatives, which is totally fine and beautiful. I love that. But I realized that there's a secondary aspect to coming together, to, I guess, transform ourselves through engaging and interacting. I'm also, as an artist, very interested in how these [gatherings] might produce possibilities for co-creation, collaboration, creative outcomes that sit uniquely on our arts landscape. Therefore, what I ended up doing was engaging with a group of dancers that I felt could bring about a really refined presentation. I’m now working with dancers who have had extensive training, who have had creative lives, who have performed and been amazing, but who, like most people, now have other jobs and children, and are just trying to survive. The youngest is 35 and the oldest is 49, so we're sort of in this later bracket, and that's unique unto itself, because it brings lived experiences which are intergenerational, and then shifts the focus from being about things that are purely to serve the performance-making, but actually become stepping stones for each of our lives, the ways that we then support our families and our other jobs and our other communities. We're trying to heal the rupture of identity between being a creative, and being a human.

We operate in a way that I could still be my mother's caregiver and still be the dance expert that I dreamed to be. What's been established is we all are better humans from having this ongoing relationship to our art and doing away with this idea that dance can only exist in a western context, dance can only happen in the short-term for a specific outcome. It's long-term for multiple outcomes, human outcomes.

One dancer is South African. One is Pakeha (a New Zealander of European descent). Another is Māori. Mitra is Persian. I've brought in a strong application of te Reo Māori, or Māori language, teaching traditional chanting, songs, which, again, is really challenging in our society, given how Indigenous languages have been treated. It's enabling us all to meet a whole history of disembodiment through voice and through language because language is the key connector to the worldview. You can study dance or language to be proficient, but we're using all of these attributes as knowledge-building, and seeing where they challenge us. It's opened up many, many conversations around genealogy, and especially around why some cultures experience erasure.

I think the common technique between us is contemporary dance. But the main form is improvisational.

In the first part of our gathering, following our witnessing of ourselves and each other through the listening process, through the sharing process, we then activate Te Reo Māori. So I will go, let's learn this song. This is how you pronounce it. This is how you make that sound. And it brings things up because people feel shy, or they make mistakes or they don't want to get it wrong. So I feel like even the learning isn't about getting it right. The learning is understanding what comes up and why that might be a thing that has prohibited people from just experiencing [something]. When it's time to move I might just give a really simple provocation, spatially or individually. We don't have a typical way of moving. There's no expectation about how we should be moving, or what is at the forefront of the aesthetic, but it's always about the inner quality, where we're dynamically engaging, as opposed to sort of softly thinking. It's about bringing our energy forward, to surprise ourselves, to extend beyond ourselves. We might do solos for a little while. We might do duets, or we might do a trio. We might do a group activation, and then we might put things together.

Another aspect of what I do is storytelling. So I might get someone to tell a random story about someplace in the world that they've been, and about something that they've eaten in Italy, for example, and everyone has to physically embody their story. And I guess what I'm really trying to get to is this idea that inherently embedded in all stories and narratives is energy, and something that can spark relationship. I’m also getting to how much we edit ourselves and never tell our stories. Ours is an oral tradition. We didn’t have a written language until missionaries came. Our other activations were carving, dancing, weaving. That’s why this idea of both talking and doing feels culturally aligned.

I'd love to keep thinking about how we can bring what we do in the studio to more people. I have a little idea to try to do these labs at the train station. Because I'm like, hey, what if I could get commuters engaging and interacting with these ideas as they're walking by? They might be like, You know what? I've got a 20-minute wait for a train and instead of waiting over there, I'm going to come and dance over here.

Tiaki Kerei in performance; photo by Anna Cucera; copyright Tiaki Kerei

Tiaki Kerei in performance; photo by Anna Cucera; copyright Tiaki Kerei

On Current Concerns

Obviously for any concerns that you identify, there are 20 more issues. But I feel like there's been a really direct attack on anything Māori by the government. For example, in the education space, they’ve proposed taking Te Reo Māori out of children's books. Yeah, totally, totally, totally, totally,

I guess it's a little bit like Covid, you know, when you start seeing it track around the world, and New Zealand gets it last. You could see it coming. You can see this, you know, this racism and this institutionalized supremacist activity on its way. Every country has a different relationship to it. So what it's done, I guess, is exacerbate a wound that was already there, the historical erasure of culture through colonization. That was always there in my generation. But also in my generation, which I'm a product of, there was the revitalisation of culture.

So I guess in the contemporary arts I want to take that one step further, which is to suggest that not only is the focus about saving the antiquity of our culture, but it's also about the future prosperity of all of the versions which we can't even assume [to imagine] yet. We want to make sure that we retain the freedom to express ourselves, reinterpreting [as we see fit] across generations, which is how our culture has always been.

I've been on a journey of wellness, understanding that I should be grateful for having had a career, and still being alive and having opportunities to really develop and explore. What I’m working on is an ecology of well-being.

There is huge potential for the knowledge that I'm reclaiming to be somehow or other gifted back to people to, first of all, cultivate their hauora – their well-being. I go back to that because it's kind of an antidote to all of the colonizing impacts known and unknown that have trickled down and embedded themselves in our structures as Māori and as people.

—---

Tiaki Kerei has been a Visiting Assistant Professor at the University of California, Riverside, an Artist in Residence at the University of California, Berkeley, and a Regent’s Scholar at the University of California, Los Angeles.