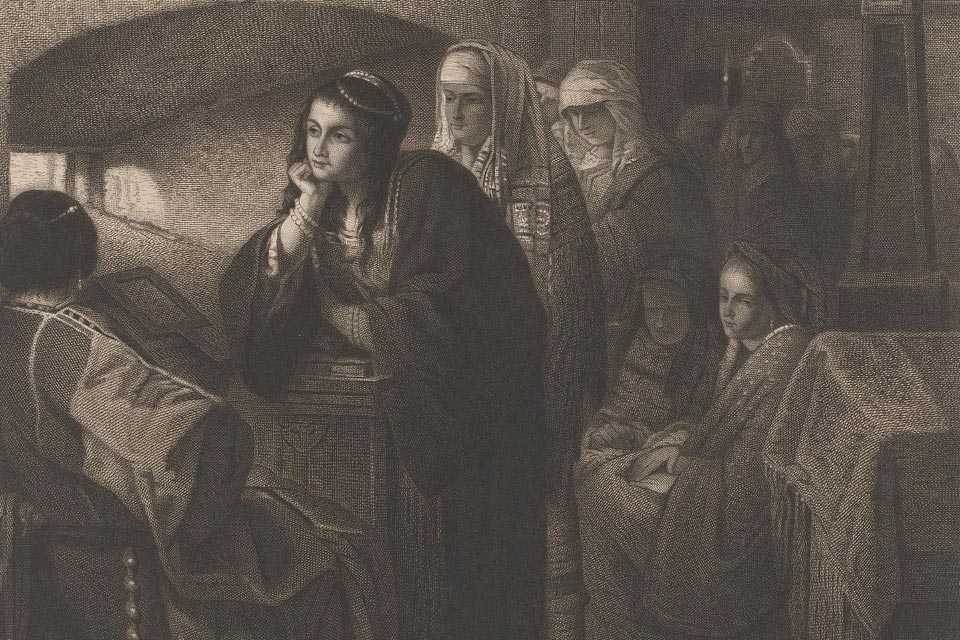

“It is the Great Day of Atonement with the Jews”

Group of women in a synagogue, Jean Baptiste Pierre Michiels, after Henri Leys (baron), 1831-1890.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of Rijksmuseum

Aug. 31, 2021

Two years ago, the Joseph H. and Belle R. Braun Professor of American Jewish History and University Professor Jonathan D. Sarna revealed that he'd made a groundbreaking discovery — the first literary American Jewish novel.

What was even more remarkable about "Cosella Wayne" was that it was published in 1860 by a woman, Cora Wilburn.

In her time, Wilburn was one of the most prolific American Jewish writers. But by the 1870s, she'd fallen out of fashion and her "woman's fate," as she described it, was to die penniless and forgotten.

The novel describes its eponymous hero's travels and travails after she's abducted by an evil gem merchant.

Of particular interest to historians are the rich and detailed descriptions Wilburn provides of Jewish life beyond America's shores in the mid-19th century.

Excerpt from "Cosella Wayne"

The excerpt below describes a Yom Kippur service in Germany in the 1840s.

It is the great day of Atonement with the Jews. Clad in the habiliments of the grave, the sweeping shroud of linen, with its wide cape edged with lace, the conical cap upon their heads, the worshipers of the ancient law read the accustomed prayers and beat their breasts in penitence. The synagogue is thronged, the gilded chandelier dispenses its rays of artificial light to the broad glare of day, and the voice of the reader rises loud at intervals in the repetition of the sacred formula: "Hear, oh Israel! The Lord thy God, the Lord is One!" and the congregation fervently responded: "Blessed be his holy name forever and ever!"

Occasionally, the sweet, softly murmured chorus of female voices lends its charm to those antique hymns of praise and penitence. The women sit above, in a gallery devoted solely to their use, separated from husbands, fathers and brothers; some, the aged and the matronly, arrayed in the vestment that once shall shroud their lifeless forms; others, the young and gay, wear dresses of pure white, emblematic of the forgiveness of sins, the stainless purity of the day of expiation ... They [the congregation] pray for the restoration of the land by them deemed holy; they weep afresh for the destruction of the sacred temple, for their scattered people and dethroned rulers. They strike their breasts, confessing their sins of commission and omission, and say aloud:

"For all this, oh Lord! King of the Universe grant us remission and pardon for thy name’s sake!"

Five times that day, the congregation fall upon their knees in worship to the unseen God, and implore his pardon for the people. They pray, too, for the earthly and Christian rulers set before them, for the prosperity of their adopted country, for the welfare of all ...

The September day drew to a close; the departing sunrays illumined the roofs and tree-tops; the evening prayer was begun; and the faint, hungry glances of the worldly minded turned to the slowly moving hands of the massive clock. The twilight deepened, and the last benediction was said; the horn of commemoration was blown twice to announce the consummated sacrifice; the return to worldly cares and duties.