A Son of the Sephardic Americas

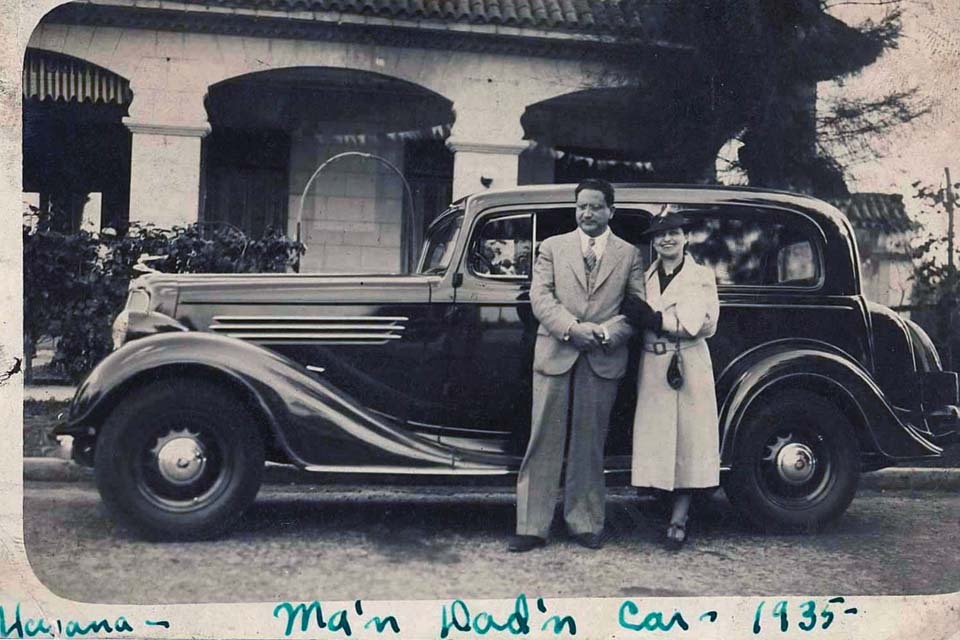

Brandon and his wife, Esther, in front of their home and car in Havana, Cuba, in 1935.

Photo Credit: Grant Brandon

Jan. 19, 2023

By Julia M. KleinJacob (Jack) Brandon Maduro was a 20th-century Jewish entrepreneur and community leader whose career took him to Panama, New York, and Cuba as he built his businesses and worked to strengthen ties among Jews in the Americas.

He is credited with aiding German Jewish refugees in Cuba during World War II and bringing the Jewish organizations B'nai Brith and Hillel to the island in 1943.

Associate research scientist Dalia Wassner sees Brandon's life as a window into the complexities of Latin American Jewish identity.

Brandon's forebears hailed from 15th-century Portugal (then part of Iberia). After settling in Amsterdam, they moved to the Caribbean island of Curaçao, where they helped found Mikvé Israel-Emanuel, today the oldest synagogue in continuous use in the Americas.

According to Wassner, Curaçao became the "mother community" for Latin America Jewry, with settlers forging bonds among Jewish communities throughout the Caribbean and the United States. In a forthcoming article in the journal Latin American Jewish Studies, Wassner writes that these transnational "networks of support" gave rise to "webs of families who [understood] their mutual responsibility to their fellow Jews."

Wassner currently serves as director of the newly established Brandeis Initiative on the Jews of the Americas, which focuses on the cultural, communal, and religious traditions of Latin American Jewry. The Initiative aims to correct the relative lack of scholarly attention to Latin American Jewry, which is estimated to number over 750,000 individuals, nearly half of whom live in the United States.

TJE asked her about Brandon, whom she calls "a son of the Sephardic Americas." (Sephardic Jews trace their lineage to Spain and Portugal.)

Tell us about Brandon's life.

He moved around a lot. He was born in Panama in 1880, lived and worked in New York for a while, then spent 30 years in Cuba, finally returning to New York, where he died. In many ways, he was a citizen of the world, but he always worked to strengthen whatever Jewish community he was in. And he had a sense of the Americas as being very connected.

What business was he in?

He first started working with his uncle in New York in banking. His cousins helped finance the Panama Canal. When he went to Cuba in 1923, he moved into the textile business, importing stockings and other clothes.

Why the move to Cuba?

In the 1920s, Cuba became very welcoming to U.S. investors. They came looking for economic opportunity and often found it. Brandon felt very much at home in Cuba. There was an entrepreneurial mentality that was part of his family's DNA.

And in Cuba, he became very involved in helping German Jewish refugees.

Yes, Brandon worked with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and the Cuban government in 1939 to take in Jewish refugees sailing from Germany on the Hamburg-Amerika Line. He worked tirelessly on this for the next three years and led the effort that saved about 8,000 refugees. In his 1953 memoir, "Memoirs and Related Observations," he recounted how he got U.S. Jews to help the effort.

What prompted him to write the memoir?

It seems to me that it was important to him to leave a record of how he helped build the Jewish community in Cuba. He dedicated it to his children and grandchildren. He was telling his descendants that we are a proud Sephardic family of the Americas — we are entrepreneurial, we seek opportunity, but we also seek to do good in the country we live in, to be conscientious world citizens.

You see Brandon's views as typifying those of Sephardic Jews who settled in the Americas.

There's a concept in Jewish history of "Port Jews" — Sephardic Jews who created networks in port cities. I see these Sephardic Jews as bringing this kind of port mentality to the communities that they formed in the Americas. The concern was not about assimilation. It was about being respected as Sephardic mercantile families who helped build what they were part of.

Sephardic Jews of the Americas brought a worldview that impacted Jewish communities of the Caribbean and Latin America. It speaks to the concept of Jewish peoplehood globally — that we're all one people.

Brandon's memoirs reveal how interconnected the Americas are, and the early Sephardic Jews of the Americas were agents of that connection. Their ethnicity, family networks, and connections across place and time were key to their identity.