The Beauty of the Hebrew Letter: A Visual Journey Through Time

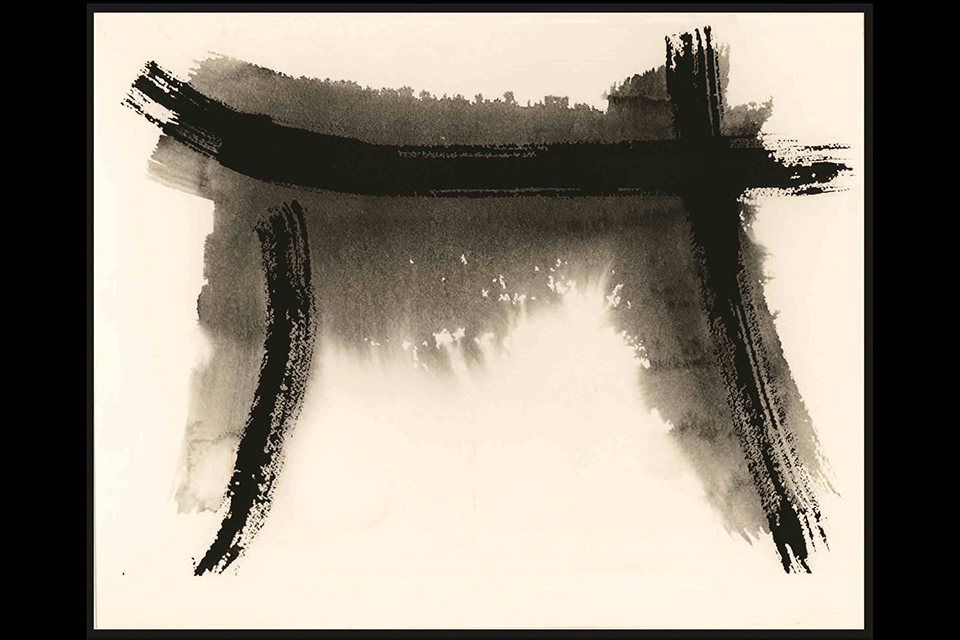

Edna Miron Wapner's Zen-influenced rendering of the fifth letter of the Hebrew alphabet, hey.

Photo Credit: Courtesy: Brandeis University Press

May 23, 2023

"A truly beautiful letter," writes the Israeli artist Izzy Pludwinski in his new book, "The Beauty of the Hebrew Letter," "will possess a dynamism, an internal lifeforce."

"Letters," he adds, "are the potential energies through which the universe was created."

Pludwinski fell in love with Hebrew writing in the late 1970s when he saw a poster in a New York City synagogue advising worshippers that a single missing letter in a Torah scroll could undercut the sanctity of the entire scroll.

"What mystical power could a single letter have?" he wondered.

His book, released in June by Brandeis University Press, highlights historical documents, artwork, fonts and typefaces, religious texts, and even graffiti to demonstrate the ever-changing beauty of Hebrew letters and writing.

"Good, strong calligraphy is like music," Pludwinski said in an interview. "It has a rhythm and flow all its own. It goes beyond the letters to express something abstract and deeply emotional."

Hebrew, which is read from right to left, likely originated sometime during the middle of the second millennium BCE, spoken and written by the Israelite tribes that settled in Canaan. When the Babylonians conquered ancient Judah in the 6th century BCE, sending many Israelites into exile, it gradually ceased to be spoken. It became primarily a written language used in much of the liturgy, rabbinical commentaries, and books of the Hebrew Bible.

It was only in the 19th century, with the rise of Zionism, that Modern Hebrew arose and then became widely used by the Jews who settled in Israel.

Below are four examples of Hebrew writing from Pludwinski's book, along with background information and his commentary.

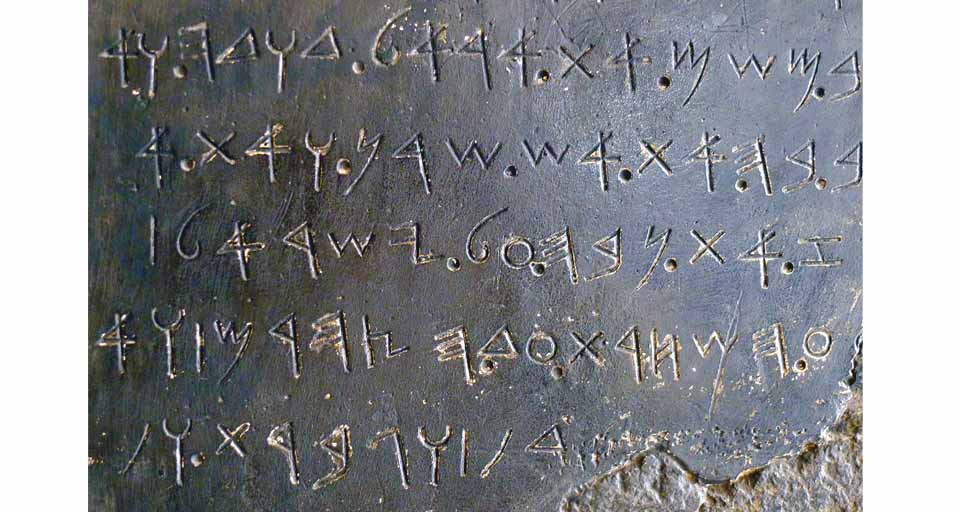

The Mesha Stele (a.k.a. The Moabite Stone)

This stele, dated around 840 BCE, is written in Moabite, which is very similar to Hebrew and like Hebrew, a Canaanite language.

The text relates how King Mesha of Moab (in modern Jordan) defeated the Kingdom of Israel. Some scholars believe that a word on the stone slab with several Hebrew letters missing may be a reference to the Bible's King David. "I wanted to take readers back to the ancient beginnings of the Hebrew language," Pludwinski said, "to show how it all began."

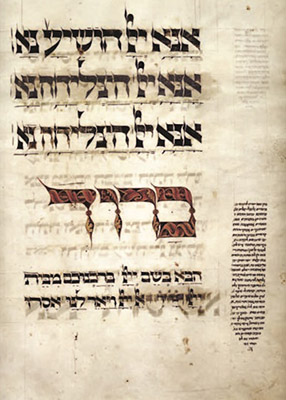

The Medieval Passover Seder

By the Middle Ages, Hebrew writing generally took two forms, one practiced by Ashkenazi Jews (Jews in Central and Eastern Europe) and the other by Sephardic Jews (Jews from medieval Spain and Portugal who later settled in Amsterdam, North Africa, and the Middle East).

Each form borrowed from the surrounding cultures. Pludwinski writes in his book, "Ashkenazic scripts were written with a quill and are characterized by extreme contrast between the thick horizontal strokes and thin vertical strokes. Sephardic scripts were written with reeds and have less pronounced contrasts."

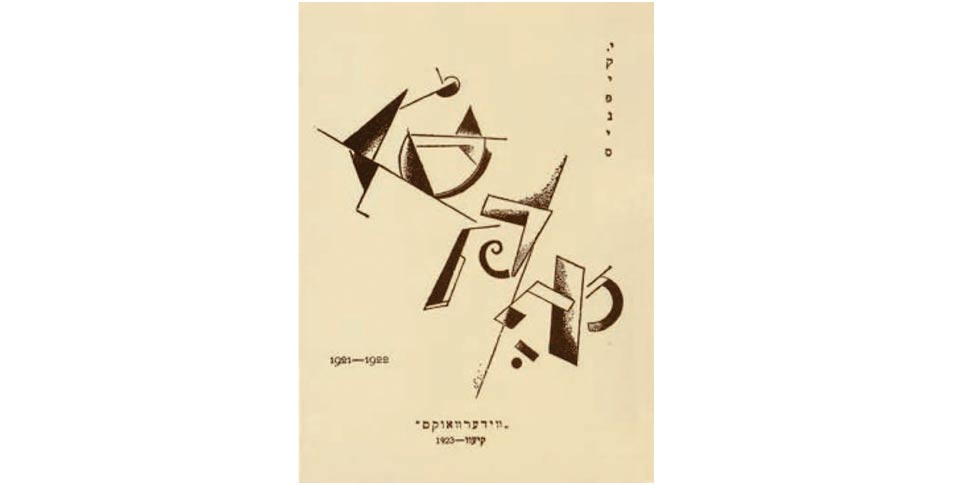

Yiddish

In the early 1920s, Jewish intellectuals launched a new literary magazine, Albatros, published in Warsaw and Berlin and dedicated to exploring Yiddish expressionist writing and art. Yiddish, the vernacular of Eastern and Central European Jews between the 10th and 20th centuries, is written in Hebrew but has more in common with Germanic and Slavic languages.

For the cover of Albatros, pictured here, the Polish-French painter and graphic designer Henryk Berlewi took wild liberties with the Hebrew language, creating letters infused with the spirit of the modernist avant-garde movement. The writing "breaks every rule," Pludwinski said.

Izzy Pludwinski, 2006

In his calligraphy, Pludwinski borrows from Arabic script to find new, more fluid forms for Hebrew letters.

He said he also "lets my hand determine the stroke rather than my brain," which leads to unexpected results. The Hebrew writing here reads, "Draw me after you, and we will run," a verse from the Bible's Song of Songs.

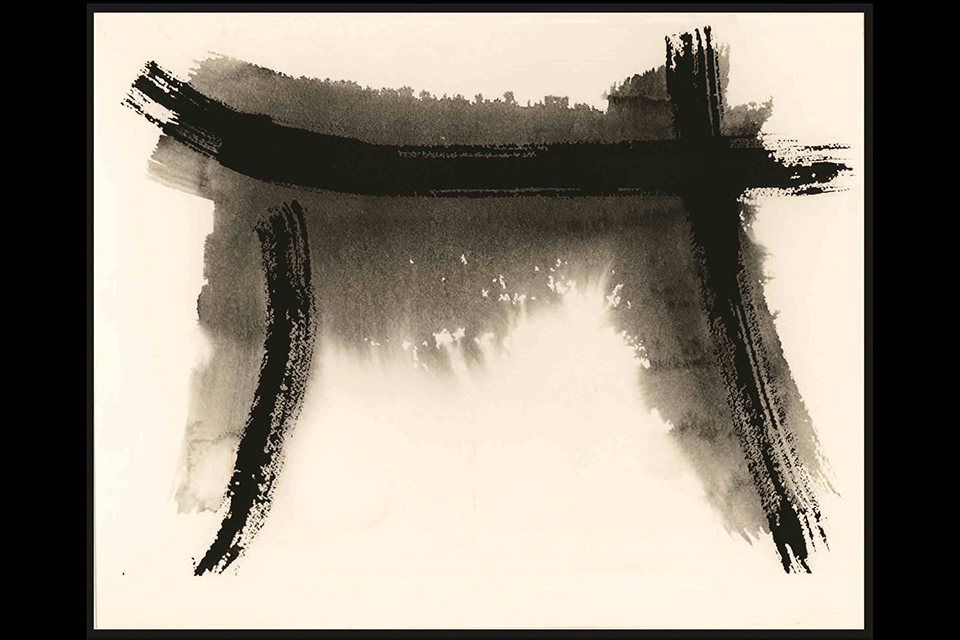

Edna Miron Wapner, 1991

Wapner, an Israeli artist, combines Jewish mysticism with Japanese Zen art to create works that, in her words, offer a "transformative art experience."

Here, she renders the fifth letter of the Hebrew alphabet, hey, using sumi ink, traditional in Japanese calligraphy and made from the soot of burnt oils. In focusing on a single letter, Wapner echoes the 13th-century book of Zohar, a cornerstone of the Jewish kabbalistic tradition that sees the Hebrew alphabet as a blueprint for the cosmos. "God looked into [the letters] of the Torah [5 books of Moses] and created the universe," the Zohar states.