The History of the Etrog in America

SeEditor’s Note: Sukkot is the annual Jewish harvest festival that commemorates the 40 years the Israelites spent in the desert in the book of Exodus. As part of the holiday, branches from the palm (lulav), myrtle and willow trees and a citrus fruit called etrog are held together and shaken.

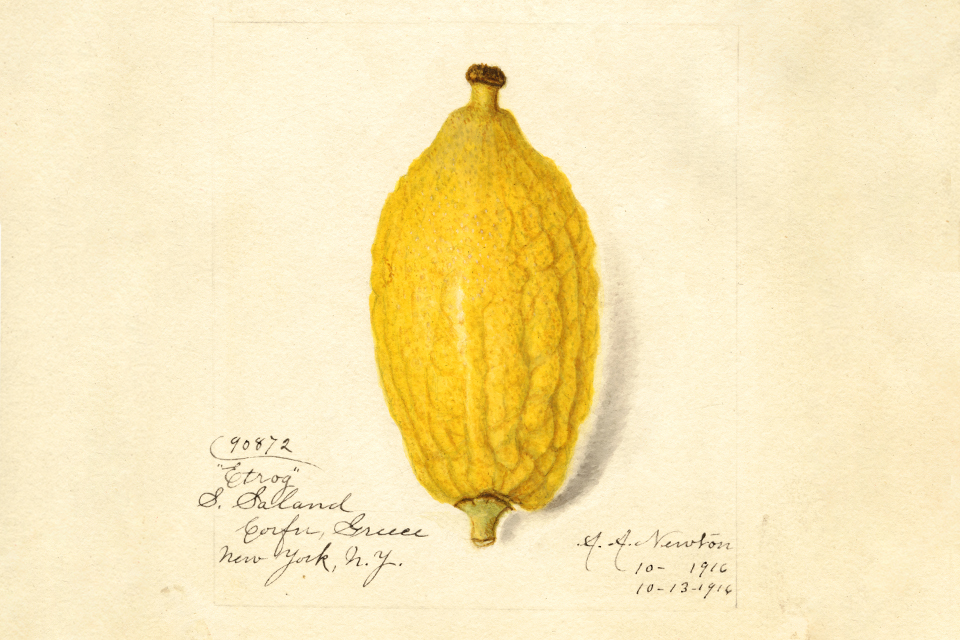

Etrog — etrogim is the plural in Hebrew; esrog and esrogim are how it was pronounced among Eastern European Jews — grow mainly in warm Mediterranean climates. This made the citrus fruit extremely difficult to come by for diaspora Jews until international trade grew more robust in the 20th century. In addition, elaborate rabbinical rules govern how the etrog must be grown and handled.

This article describes the fraught and controversial history of the etrog in America. It first appeared in a more extended version in Segula, a Jewish history magazine, and has been reprinted with permission.

Sept. 17, 2021

By Jonathan D. Sarna '75, MA'75, and Zev Eleff, PhD'15

In 1882, etrogim in Los Angeles were a bargain: just 25 cents each.

"They are beautiful to behold and will compare favorably […] with any that have ever been imported to this country," reported "Maftir" (Isidore Choynski), West Coast correspondent for the American Israelite. These locally produced etrogim, grown in America's new citrus capital, appeared to solve what had previously been a significant religious problem. As Rabbi Moses Weinberger of New York explained in 1887:

Only a few years ago, a poor man in New York could not buy a lulav and esrog of his own [as part of the four species taken on the festival of Sukkot]; even the most highly Orthodox had to observe the commandments with esrogim circulated around every morning by poor peddlers. Now it is hard to find any kosher traditional home without an esrog of its own. In many synagogues, especially the small ones, there are as many esrogim as worshippers.

Within a few years, however, U.S. etrog production had almost completely ceased. Contrary to conventional economic wisdom, expensive, imported etrogim triumphed over the cheaper, domestic variety. To understand why, we'll have to journey back into the early-19th-century history of the etrog in the New World.

From Corsica to the Caribbean

During the first decades of the 1800s, American Jews had three sources of etrogim: Corsica, the U.S. itself and the Caribbean. The finest and most expensive came from Corsica, under French rule. …

Two factors diminished the popularity of these etrogim, however.

- First, many turned out to be grafted (murkav), which made them much stronger and better able to grow and travel but violated the biblical ban on kilayim (mixing species).

- Second, trade with France and Italy was greatly disrupted by the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815). During this era, very few diamante [from Corsica] etrogim made it to the New World; other sources had to be found.

The Upside-Down Etrog

The most unusual response came in 1836 from one of central Europe's leading rabbis, Yaakov Ettlinger. … In Europe, reasoned Ettlinger, the standard practice of holding an etrog with its protrusion or "pitom" upmost would mean that a Southern Hemisphere citron was in fact upside-down, violating the rule that all four species must be held and shaken in the manner in which they grow.

While dubious science, Ettlinger's responsum [a written decision from a rabbinic authority] fortuitously permitted those in the New World to continue using New World etrogim, while protecting European etrog producers from cheap New World competition.

Etrog as Metaphor

The ensuing decades saw etrogim from various places sold in the United States. Business boomed, largely because sugar prices dropped and candied citrons became a highly popular American treat.

Which of these imports were actually kosher for use on Sukkot continued to be debated, but at the end of the day, much as local Jews could choose among different rites and movements and synagogues, they could now choose among etrogim from different locales: very expensive ones from Corsica or Corfu; cheaper varieties from the Caribbean; and, with the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, growing numbers of citrons from sunny California, where citrus of all kinds thrived.

Interestingly, these three etrog sources reflected three different conceptions of America's place in the global Jewish economy.

- Those who demanded European etrogim for Sukkot considered them the most reliable and believed that American Jews should follow the same standards and use the same ritual objects as their European counterparts; that the United States, in short, should be part of the European Jewish religious sphere and market.

- Those who endorsed West Indian etrogim, by contrast, located the U.S. within a vast New World Jewish religious economy – distinct from Europe – with suppliers in North and South America catering to its clientele's every need.

- Finally, those who began developing the California etrog trade – which peaked in the final decades of the 19th century, sending etrog prices plummeting to a mere twenty-five cents – seem to have imagined the United States becoming an independent Jewish center, producing its own four species along with its own Hebrew books and rabbis.

Holiest of All

In September 1877, a scant decade after regular steamship service from New York to Palestine was inaugurated, newspapers in the Big Apple announced that J. H. Kantrowitz of 31 East Broadway had "imported from the Holy Land a choice lot of Esrogim." … Etrogim from the Land of Israel were small and scrawny, lacking the visual appeal of those produced elsewhere. But whatever they lacked in appearance, they made up for in sanctity, justifying their hefty price tag.

As the etrog growers of the Holy Land were known to be pious Jews, no one could question their product's halakhic fitness. In addition, money expended on these etrogim helped support Palestine's struggling Jewish community (the Yishuv) as well as the nascent Zionist movement, making their purchase doubly commendable. …

Then, in April 1891, the death of a young Jewish girl in Corfu prompted a well-publicized blood libel, resulting in massive anti-Jewish violence and the emigration of the majority of the island's Jews. In response, many Jews boycotted Corfu products, etrogim included. …

Corfu's etrog growers never fully recovered. Instead, in the 20th century, orchards in Jaffa and Petah Tikva [in Israel] took the lead as part of a larger, Zion-centered restructuring of the global Jewish economy, which affected ritual objects of all sorts. For the better part of the last hundred years, a substantial majority of the etrogim sold in the United States have been imported from the Land of Israel – though they cost a lot more than 25 cents each.

About the Authors

Jonathan D. Sarna is Distinguished University Professor and the Joseph H. and Belle R. Braun Professor of American Jewish History at Brandeis University. He is also a member of Segula's advisory board.

Zev Eleff is president of Gratz College in Pennsylvania, where he also serves as professor of American Jewish history.