The Long, Ugly Antisemitic History of "Jews Will Not Replace Us"

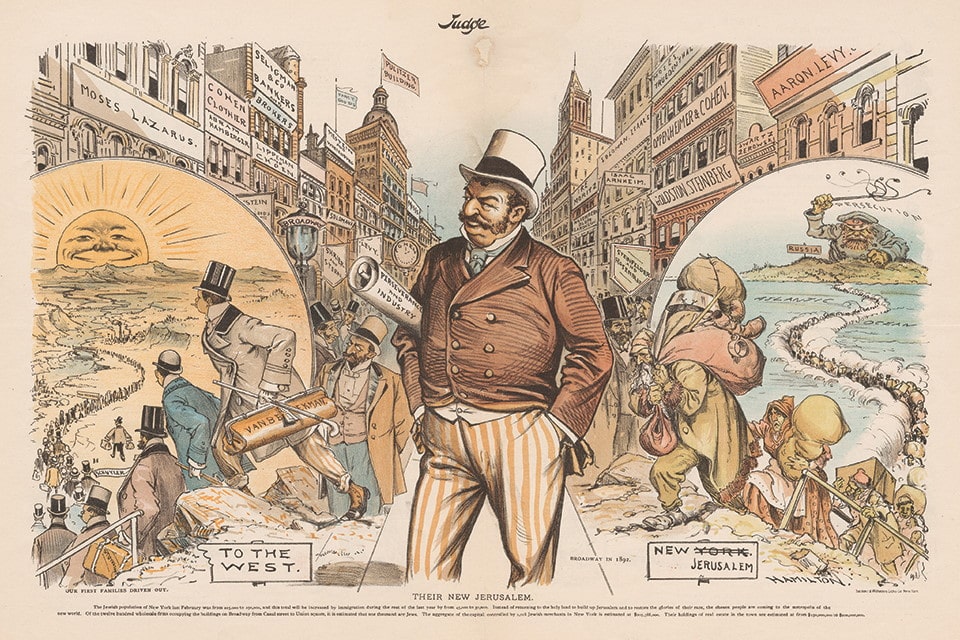

An antisemitic cartoon from Judge magazine in 1892. On the right, Jews stream into New York City, turning it into "New Jerusalem." All the businesses now bear signs suggesting they are owned by Jews while, to the left, Americans who originally settled the city head to the West. "Our first families driven out," the cartoon reads.

This article is republished from The Conversation. Jonathan Sarna is University Professor and Joseph H. & Belle R. Braun Professor of American Jewish History at Brandeis.

Nov. 19, 2021

By Jonathan D. Sarna '75, MA'75

"Jews will not replace us," demonstrators chanted at the Unite the Right rally organized by armed white nationalists in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017, to stop the removal of a statue dedicated to Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee.

Heather D. Heyer, a 32-year-old paralegal from Charlottesville, was killed, and 35 others were wounded when a 20-year-old neo-Nazi, James Alex Fields, intentionally drove his car into a crowd of counterprotesters during the rally.

Now a federal trial in Charlottesville aims to extract damages from those who organized and led the deadly rally.

Lead plaintiff Elizabeth Sines, a law student at the University of Virginia at the time of the rally, believes that the lawsuit carries an important message. In an interview with The New York Times, she said, "If you plan and execute violence – toward Jewish people, people of color, diverse communities like Charlottesville – you will be held responsible for your actions."

At first glance, it might not be clear what the demonstrators meant in chanting "Jews will not replace us."

Only about 2,000 Jews live in Charlottesville, out of a total local population of 47,000. Nationally Jews number no more than 7.6 million, meaning that just over 2% of Americans are Jewish. Indeed, recent studies suggest that America's Jewish birthrate has fallen, and Jews are barely replacing themselves, let alone the white population as a whole.

What, then, could explain Charlottesville demonstrators' fears?

The Role of White Nationalism

Scholar of Jewish history Deborah Lipstadt, MA’72, PhD’76, H’19, who has been nominated by President Joe Biden to serve as special envoy to monitor and combat antisemitism, argued in an expert report presented to the court concerning the history, ideology, symbolism and rhetoric of antisemitism – subsequently summarized in her personal testimony – that the Charlottesville chant carried several meanings.

"In its simplest and most straightforward interpretation," she explained, "that chant can be understood to say Jews will not replace 'us,' i.e., white Christians in our job or our dominant place in society. We as whites will remain the dominant and supreme force in society."

She also pointed to a "subtler but deeply ideological meaning to this chant," rooted in the fear referred to by white nationalists as the "great replacement" or "white genocide." The Charlottesville chant is expressing centuries-old fears that Jews, in league with peoples of color, are engaged in a nefarious plot to destroy the white Christian civilization.

David Lane, a white supremacist convicted, among other crimes, of conspiring in the 1984 machine-gun assassination of the Jewish talk-radio host Alan Berg in Denver, did much to publicize this idea. "The Western nations," he wrote, "were ruled by a Zionist conspiracy … [that] above all things wants to exterminate the White Aryan race."

His 14-word goal, today a central plank of white nationalist ideology, declares that "we must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children."

Alex Linder, a neo-Nazi who operates the racist website the Vanguard News Network, has written that Jews merely pretend to be white "in order to shame, discredit, blame, mock, harass and otherwise discomfit and discredit white people and the white race."

The chant "Jews will not replace us," Lipstadt explained to the court, serves as the white nationalist response to these fears. To avoid "catastrophic takeover," it calls upon white people to "band together, arm themselves and go on the offensive," she noted.

Lipstadt dates this antisemitic theory back to early 20th-century tsarist Russia, where a notorious forgery, now known as "The Protocols of the Elders of Zion," purported to "prove" that Jews were engaged in a vast conspiratorial plot to subvert Christian society and culture. According to the protocols, Jews aimed at nothing less than world domination.

Today's antisemites likewise believe in a vast Jewish-led conspiracy that seeks to undermine all that they hold dear. The cry "Jews will not replace us" reflects this fear and, according to Lipstadt, served as "one of the motivating underpinnings of the Unite the Right rally."

Lipstadt's evidence is persuasive, but, as a scholar of American Jewish history, I know that the fear of "replacement" dates back even earlier.

The "New Jerusalem"

In 1882, with thousands of Jews pouring into New York in the wake of Russian pogroms and anti-Jewish legislation known as the May Laws, similar fears surfaced, even though Jews at that time made up far less than 1% of the U.S. population.

The well-known American-born cartoonist James Albert Wales, who died in 1886, stoked fears about how Jewish immigrants would change the city's character, in depictions in the satirical weekly The Judge.

Wales portrayed New York as becoming, by 1900, the "New Jerusalem," where Canal Street would be renamed "Levi Street,"

Jewish-owned businesses would replace Christian ones and a Jewish feather merchant would serve as the city's mayor. He portrayed long-nosed Jewish soldiers as a militia of pawnbrokers parading down Broadway.

They were seen to be supplanting the so-called bluebloods of the famed 7th Regiment of the New York Militia, the city's prestigious national guard founded in 1806 and mustered into federal service during the Civil War.

Published on July 22, 1882, as a colorful two-page chromolithograph, a colored picture printed by lithography, the cartoon was one of a series in The Judge that warned readers to beware of Jews, who supposedly looked to replace them.

Another of Wales' black-and-white cartoons, titled "The Dream of the Jews Realized," which likewise appeared in The Judge in 1882, depicted an imaginary Jewish celebration marking the removal of the city's last store sign with a characteristically white Christian name, "John Smith," an enterprise purportedly established back in 1820.

Replacing it was a sign bearing the Jewish name "Moses Eichstein." In the background of the cartoon, a banner illumined by upraised thumbs, considered to be a typical Jewish hand gesture, gave voice to the nativist fears that The Judge sought calculatingly to inflame: "We own the Town," it announced.

The 2017 Charlottesville chant, "Jews will not replace us," reflects those same kinds of fears.

As the trial in Charlottesville now moves toward its conclusion, it bears recalling that the fantasy that Jews seek to recreate America in their own image, to the disadvantage of white natives, is as old as mass Jewish immigration to America's shores.