Why 'Zoom Judaism' Will Never Work

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s and not necessarily of Brandeis University.

Aug. 31, 2021

By Eric Yoffie '69

What will Jewish life be post-pandemic?

Jews will run back to the synagogue. They will not drift back; they will run back.

Yes, adjustments will be made: The Jewish communal world will rethink the need for large facilities and will reduce infrastructure costs. Digital tools will be more important.

Synagogue and JCC memberships will be somewhat smaller. And Zoom worship will remain a fixture for those who need it (Virtual worship has made the synagogue more accessible, and that is a blessing).

During the pandemic, the Jewish community needed to be more resourceful — and it was. We needed to make use of technology in a sophisticated way, and we did. As a result, our Judaism is more hybrid, inclusive and creative.

But what we have learned, more than anything else, is how much we miss tactile, face-to-face Judaism. Zoom Judaism is wonderfully convenient, but alas, it is also, ultimately, religiously unfulfilling and terribly isolating.

And precisely because some of what we have been doing during the pandemic will be permanent — many, many Jews will spend more time working at home — not 5 days a week but 2 or 3 days a week — the in-person dimension of synagogue life will become that much more important.

The communal aspect of the synagogue is the beating heart of our Jewish experience. Absent community, Judaism survives barely, if at all; our ritual is barren, our worship withers, and we struggle to study Torah. Better death than solitude, the rabbis teach — o chavruta, o mituta.

This is hardly a new insight, of course, but in the last half century, it is something that has become more and more apparent. Most American Jews no longer live in Jewish neighborhoods. They no longer have grandparents who live down the block and who are there for Jewish holidays and for babysitting.

In this new American reality, despite endless moaning about the inadequacies of congregations, the synagogue has become more important than ever. It is there that Jews find the community that they have been missing, help in raising their children, and the sense of holiness that community fosters.

And the pandemic, interestingly, has made us appreciate the synagogue in ways that we did not before. We see now more clearly than before that it is the synagogue that enables us to find religious support in a lonely world.

It is often the only place that always cares about you as an individual, and where if you are not there someone misses you. It is the one place where no one suffers alone or grieves alone.

But community cannot truly flourish if it is virtual. It cannot, no matter how many times experts tell you it can.

We know this from the data: four in 10 U.S. adults had developed symptoms of depression or anxiety by the end of 2020, the year of doing things online. According to the UCLA Loneliness Scale (which is the gold standard of such things), 61% of Americans are measurably lonely. No matter how many Zoom sessions we may have, virtual experiences leave us isolated, and isolation is not our natural state.

The net can offer information, novelty, a variety of fleeting attachments, and an outlet for passionate political opinions. But it cannot offer meaningful friendship, real community, or vibrant and authentic Judaism.

And we know this too from Martin Buber. In the mid-20th century, he presciently warned us to beware of television, computers and technological aids when we thought about how to educate the young and pass on Judaism to others.

Such things, he said, could convey information, but the essence of Jewish education and transmission is the direct bond between teacher and student and what one person learns from another.

What all this means is that when the pandemic is over, the synagogue, if it seizes the opportunity, will thrive as never before. It will be uniquely positioned to offer a Judaism that will be desperately needed and personally transformative, built on face-to-face encounters.

God insisted on meeting with Moses panim el panim, face to face. And if Jews of the synagogue wish to retrieve the Jewish soul from oblivion and unveil life's fundamental holiness, they will do as God did — practicing Judaism face to face, and not on the screen.

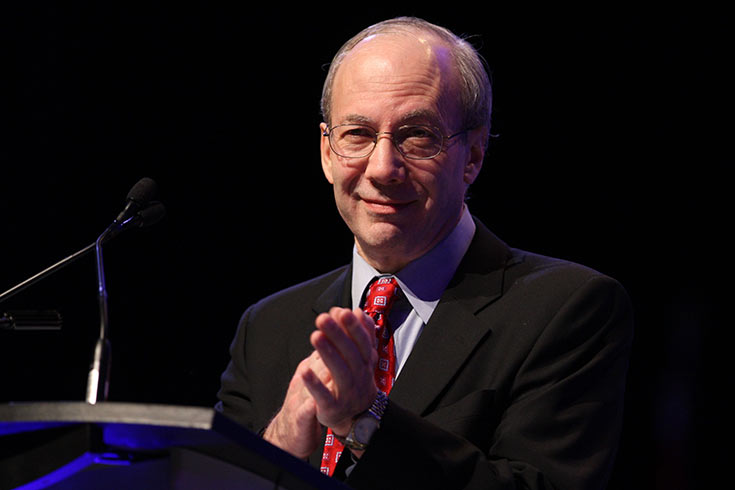

About Eric Yoffie '69

Eric Yoffie is the former president of the Union for Reform Judaism (1996 to 2012). His writings may be found at ericyoffie.com.