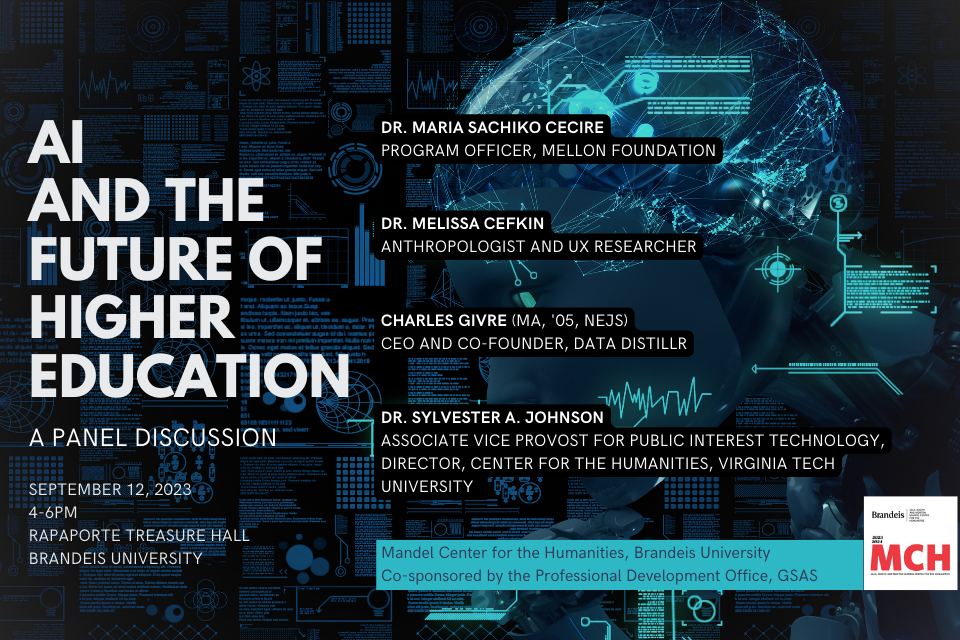

AI and the Future of Higher Education

Future of Higher Education

By Esha Senchaudhuri

Imagine designing an autonomous vehicle to navigate along a city street. It is built with sensors that feed into algorithms that use countless probability distributions to predict the behavior of humans, animals and other objects that come across the vehicle's path. How should a designer determine which objects are sense-worthy?

Dr. Melissa Cefkin, an anthropologist who works at autonomous vehicle provider Waymo, considers the role that an umbrella might play in the design of this vehicle. Oftentimes an umbrella is a superfluous object, not as important as a human being or a building. In other contexts, umbrellas might indicate cafes or recreational spaces, and this assessment will enable the machine to make clearer guesses about human behavior.

In recent years, private sector companies ranging from Waymo to Boeing to Microsoft and Google, have integrated humanists with their technologists to build systems that can respond to questions like the one above. This, in turn, has implications for how higher education institutions might consider the mission of the humanities when developing curricular practices, educational goals, and collaborative spaces for STEM and humanities specialists to engage with each other's worlds.

According to Dr. Maria Sachiko Cecire, a Program Officer for Higher Learning at the Mellon Foundation, the integration between the humanities and technology has always existed. It simply hasn't always been recognized as such by universities. Since technology now has to exist within a social sphere, questions about horror, beauty, truth and justice, are also now questions about technology. In other words, technology and engineering are positioned to become liberal arts subjects.

This reflects what Dr. Sylvester A. Johnson sees as the dual-frontier of a high-tech society. The Dean of Public Interest Technology at Virginia Tech, Dr. Johnson recognizes that technology has both a technical and a human frontier. Its mission spans creating value as well as raising new questions about equity. He notes that in its own way, questions of technology and technological innovation, particularly in a high-tech society, are essentially questions about capital: who owns technology, who pays for technology, and how is technology distributed?

Brandeis alumnus and former CIA analyst Charles Givre also notes that technology has the potential to equalize opportunity. As a simple example, extracting value from data used to fall within the purview of those with access to rare technical skills. The proliferation of technology has meant that even small businesses can benefit from the value of data, thus creating new streams of value creation. On the other hand, it creates new questions about privacy and safety.

To get a clearer sense of the full scope of the humanistic dimensions of a technological society, and how universities can contribute to its proper governance, click the video above to watch the panel.