Using a Theoretical Lens to Support Your Claims

From Darwinian Dating — Elissa Jacobs

The EVIDENCE from the papers tells you about what women want in modern studies. This is the only evidence we have about female preference (since there is no record of female preference prior to modern history).

That doesn’t mean, though, that you can’t comment on why these preferences may have evolved. Theorists (e.g., Buss, 1994) have considered why certain nice guy and bad boy traits may have been selected for during human evolution. This theory isn’t absolute (there are no ‘facts’ in science), but it’s logical and consistent with evidence.

Buss gives convincing theory for why women should like nice guys AND bad boys. The only way you can truly answer which type of men women really want more is from the evidence.

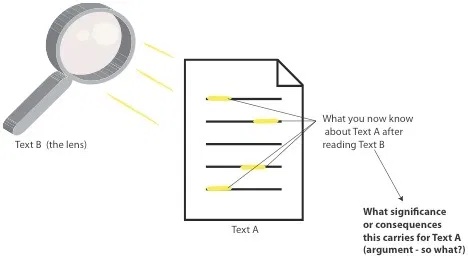

Once you’ve made your argument, you can apply Buss’s theories (as well as the theories of the other authors) to help explain your findings. If you are arguing that nice guys are preferred, WHY does this make sense? If you are arguing that women prefer bad boys, why is this a smart preference? If you are arguing a nuanced argument (bad but not too bad, nice but not too nice, too dangerous, etc.), how can you use the theory to make sense of your claims? Use Buss as A LENS to better understand your argument.

The Lens

Examples from a sample essay:

[6] Women’s instinctive desire for good genes illustrates a key evolutionary principle: “nice guys” lose out because niceness alone is not sufficient to compensate for an inferior genetic package. Certainly, niceness is a positive attribute – the resources of an invested mate will help children’s chances of surviving (Buss 1994). But the typical nice guy offers this better investment at the expense of bad genes. And since genes cannot be changed, the transmission of subpar genes to offspring is guaranteed. Moreover, men with bad enough genes can even damage the next generation through non-genetic mechanisms. An incompetent mate who struggles to provide may drain family resources; a sickly mate may infect children and even die, forcing his partner to seek a new mate; a low-status mate may confer social ostracization to children (Buss 1994). And though the appeal of the nice guy, of course, lies in the resources and protection he offers, the weak, low-status nice guy may only possess limited resources to channel into children and inferior strength to fend off attackers. Simply put, if a nice guy’s extrinsic characteristics are bad enough, his intrinsic niceness approaches irrelevance. The guaranteed genetic disadvantage and questionable provider ability of nice guys tip the scale towards bad boys; thus, women seek men who meet a sufficient level of genetic quality.

[7] Evidence / Analysis paragraph that women don’t like men who are too bad.

[8] This response is rooted in evolutionary logic: extreme bad boys trigger fear, not desire, because of the risks they pose. Most obvious is the danger of physical harm. Extremely bad boys may possess both the strength and temperament to abuse women or – even worse – their own children, which directly impedes the fitness of their progeny. Indeed, Buss (1994) notes that wife-beating is a widespread phenomenon observed across a number of cultures; given the frequency of this phenomenon, women may have evolved away from mating with violent men. A highly promiscuous, volatile man is also unlikely to ever settle down, fully extinguishing the hope of a future together. And all this – increased risk of violence and abandonment – does not appear to come at the benefit of better genes. Aggressive, domineering men are perceived as no more physically or sexually desirable than men who are simply dominant (Sadalla et al. 1987). In other words, the very bad boy offers a decrease in parental investment, to the point of directly impeding the wellbeing of his family, but without a gain in genetic fitness. Thus, women reject a domineering, aggressive man as a liability who cannot be justified by good genes alone.

** Note the way the writer uses Buss (and others) to support her claim that preference for a bad boy (but not too bad of a boy) is smart and evolutionarily grounded.

References

- Buss, D. M. (1994). The Strategies of Human Mating. American Scientist, 82(3), 238–249, https://www.jstor.org/stable/29775193

- Sadalla, E. K., Kenrick, D. T., & Vershure, B. (1987). Dominance and Heterosexual Attraction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(4), 730–738. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.4.730