Suffering Redefined

The Animal Liberation Front’s Subversion of Utilitarianism

by Leeza Barstein

Research Essay

Undermining Power: Subversion and Resistance

Instructor: Alexander Herbert

Fall 2019

About this paper | This paper as PDF : MLA format

The complex relationship between animals and humans has long been influenced by society’s stance on consciousness, suffering, and hierarchy. Whether looking at Darwin’s Origin of Species, the captivating relationship between Jane Goodall and chimpanzees, or even the modern-day trend towards veganism, it is clear that animals and humans have an intricate, often mutualist relationship; however, with the integration of modern technology into mainstream culture, the balance between acts that exploit animals and the advancement of human lives has become convoluted. The Animal Liberation Front, an animal activist organization, has directly confronted society’s hierarchy of species and subverted the principles and systems that established this divide. Subversion is based on three intermingled principles: concretely recorded ideology that rejects common belief systems, direct action that manifests from this clearly stated philosophy, and change that is incited from these actions. Although direct action may take many forms, subversion requires that acts impose damage to the targeted people, property, or business. The ALF created a concrete ideology, rejecting the common utilitarian understanding of humanity’s relationship to animals; it directly acted against the sources of animal suffering, and it used this action to prevent further exploitation of animals. Thus, it was an effectively subversive group.

By looking at rights through the contrasting perspectives of biomedical researcher Carl Cohen and philosopher Jeremy Bentham, it is evident that the ALF’s ideology drastically subverted the scientific community’s interpretation of utilitarianism and the mainstream understanding of rights within society. According to Cohen’s view on utilitarianism, the ability to make moral claims is the only requirement for having rights, and animals, devoid of language, can neither present moral claims nor defend them (886). Therefore, it cannot be inferred that for animals, “simply being alive [is] a ‘right’ to life” (866). On the contrary, rather than viewing rights as arbitrary rankings based on the complex abilities of individual species, Bentham claimed: “Rights are … the fruits of the law, and of the law alone” (125). Thus, in order for a society to exist, rights must not be inherent, assumed, or natural, but rather prescribed and allocated through a system of laws. In an interview conducted with the ALF to describe the reasoning behind their break-in to an animal research lab, one member explained that their actions were a response to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s failure to protect animals from lab testing. The member claimed that according to the Animal Welfare Act, “…you can do anything you want to an animal … the experimenter doesn’t even have to use anesthesia” (McClain 2). Through this explanation, the ALF expands on Bentham’s notion that rights, or a lack thereof, are what deem a being powerless, and since laws did not provide protection for animals, it would be the ALF’s responsibility to incite change (Bentham 125). In other words, the ALF’s reasoning lay on the premise that animals were not devoid of rights because of inherently being less deserving of them, but because the American legal system failed to enforce legislation for the equal and ethical treatment of animals in laboratories. Since the ALF’s ideology challenged the common methods of assigning rights to beings, they achieved the first principle of subversion, which requires a concrete ideological rejection of society.

However, the ALF’s ideology did more than just subvert how non-human rights ought to be defined; it also rejected a common belief system that philosopher Peter Singer refers to as “speciesism.” According to Singer, the practice of speciesism not only deems humans as superior to other animals, but also calls for non-humans to suffer based on their utility to people. Most people in society are speciesists, and this stems from the failure to acknowledge that “the capacity for suffering” entitles animals to “equal consideration” (Singer 5). In an interview, an ALF member directly rejects this common thinking: “The philosophy that drives the ALF is the belief that animals do not belong to us. They don’t exist for our use” (McClain 2). This statement immediately dismisses the notion that animals are commodities whose suffering should be disregarded for people’s benefit. The ALF further refuses to take a speciesist standpoint in a pamphlet stating their goal “of liberating animals from places of abuse … and placing them where they may live out their natural lives free from suffering” (Animal Liberation Front 3). Since suffering determines what acts are and are not ethically permissible towards a species, the ALF acknowledges that the only way to include animals in the definition of a utilitarian society is to acknowledge and consider their capacity to suffer (Singer 8). In fact, by dedicating their entire mission to removing animals from environments that strip them of their autonomy, they directly reject the common notion that based on the hierarchy of species, animals do not deserve equal consideration.

Having used writing and speech to establish an ideology that challenged conventional ideas of morality, the ALF fulfilled the next requirement of subversion, direct action, by acting against what they viewed as faulty power structures. Members used their settled ideology to act against what Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer describe as the culture industry’s grasp on pleasure. According to Adorno and Horkheimer, the most powerful members in a capitalist society—big businesses and politicians—standardize the population’s beliefs by only tolerating those who identify with behavior that strengthens the culture industry (147). In order to maintain this power, the industry relies on a system of exchange: as members of society personally and financially support the industry, the industry tolerates and gratifies consumers with material rewards. However, Adorno and Horkheimer also claim that “to be pleased means to say yes … by desensitization … by forgetting suffering even where it is shown” (144). Whenever consumers choose to ignore the suffering associated with the meat they consume or the animal-tested products they use, this blind eye “desensitizes” them to the atrocities behind their financial and moral decisions. To demonstrate this desensitization in their pamphlet, the ALF sarcastically includes a cartoon labeled “The Voice of the Honorable Opposition” (Animal Liberation Front 27). As the focal point of the piece, a decrepit man stands against a post, mocking the ALF for being “bunny-lovin’ nutcakes.” Drawn with a long, wrinkly face, straight eyebrows, and squinting eyes, the man appears to be numb and emotionless, depicting how the culture industry removes the shock value from the mistreatment of animals; however, at the same time, he is fenced in by the post he leans against which is entwined in barbed wire, demonstrating that the culture industry holds him captive not only as a consumer, but also as a thinker analyzing moral standards. With this critical cartoon meant to mock and shame consumers publicly, the ALF broke the cycle of “pleasure” Adorno and Horkheimer associate with passivity. Instead, they actively rejected the industry’s “toleration” and “gratification” of consumers and painted them in a negative light to instill feelings of humiliation, discomfort, and disgrace. By attacking consumers with the hopes of destroying their conception and experience of pleasure, the group acted against the mainstream trend of glorifying the supporters of industries testing on animals.

In addition to targeting consumers on a personal level, ALF members rejected the services of unethical organizations, refusing to participate in the economic funding of these businesses. Stated clearly in their pamphlet, the primary way members dismissed businesses was through “not eating animal flesh, and many of them [using] no animal products at all” (Animal Liberation Front, 4). By individually refraining from financially supporting the standardization of consumption, and consequently, suffering of animals, members refused to mindlessly consume. Adorno and Horkheimer refer to this mindlessness as “Capitalist production so confining [consumers], body and soul, that they fall helpless victims to what is offered them” (133). Not only do Adorno and Horkheimer deem consumers to be powerless within a capitalist society, but they also explain that through this loss of power, consumers have no choice but to financially support and benefit industries. ALF members, however, refused to be powerless victims; they refused to be “desensitized” or to “forget suffering”; in fact, they completely repudiated the culture industry’s control over citizens and used their role as consumers to support their cause. By acknowledging that businesses actually relied on consumers to buy their products, not the other way around, the group threatened the monetary gains of the culture industry, even though on a small scale. Through breaking the cycle of passive internalization in society by damaging the incomes of industries, the ALF continued to be subversive, using direct damage to incite change.

The ALF further subverted the culture industry by using direct action to inflict more widespread economic damage on animal testing labs. Specifically, to weaken the economic standing of the pharmaceutical company Huntingdon Life Sciences, the ALF relied on going undercover to expose what they deemed as unethical practices towards animals: “lab technicians simulating sex with animals, punching beagle puppies and violating numerous animal welfare regulations” (Brown). After being exposed, not only did Huntingdon Life Sciences lose their listing on the London Stock Exchange, but the company, “teetered on the brink of bankruptcy” (“Animal Liberation Front Attacks Huntingdon Life Sciences Supplier”). The ALF justified economic sabotage based on the principle that “Where money is involved, people won’t give up until … they see that their dirty business is not going to profit them” (Animal Liberation Front 18). Because researchers profited from the commoditization of animals, the only way to put an end to suffering would be to refrain from being a passive consumer and remove the monetary incentives behind animal testing.

Adorno and Horkheimer complicate the relationship between commoditization and consumption when they claim, “the stronger the positions of the culture industry … the more summarily it can deal with consumers’ needs … controlling them, disciplining them” (144). They acknowledge that economic prosperity not only gives businesses the ability to commoditize materials, but also to commoditize the consumers that support them. Instead of falling victim to the culture industry’s “control” and “discipline,” the ALF targeted the root cause of Huntingdon Life Sciences’ power—their money. Because the most powerful way to infringe on a business within a capitalist society is to prevent it from further making monetary gains, the ALF’s decision to expose the lab’s horrendous actions prevented the further suffering of animals. Seeing as the ALF’s direct actions targeted and effectively weakened the power of animal-testing labs, they successfully completed the final requirement of subversion—to use ideology and direct action to incite change.

In addition to using economic sabotage, the ALF continued to incite change through direct actions by forcing animal testing labs to shift their priorities. In the case of the Silver Spring Monkey’s, the ALF worked in conjunction with People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), to steal 17 mistreated monkeys from the Institute for Behavioral Research (Saperstein). Primarily by exposing the labs that tested on animals, the ALF subverted Adorno and Horkheimer’s notion that people are “completely expendable and utterly insignificant” (145). Rather than passively following the assumption that there is a hierarchy of species, the group spread footage from the lab to make other members of society conscious of the atrocities associated with the culture industry. By exposing the Institute’s unethical practices, the ALF sent a message to laboratories that they could not continue animal testing without any repercussions. In other words, if they wanted to maintain a good reputation, these industries would need to change their priorities and practices. The ALF acknowledges the power and impacts of their subversion, explaining that “Damage to property does save animals … laboratories have to spend more money on security … money that would have been spent on experimentation” (McClain 3). In this case, with “damage to property” being the loss of their testing subjects, the monkeys, the lab lost time and money that would otherwise be invested in creating suffering. The ALF proved they are anything but “insignificant” in society and used their direct, subversive action to reduce the effectiveness and productivity of animal laboratories.

Furthermore, in the case of the Silver Spring Monkeys, the ALF used direct action to infringe on the personal rights of researchers and their freedom to continue practicing. Because of the released documentation of the monkeys’ retched living conditions, there was a, “landmark case, [a] court battle to decide the monkeys’ fate” (Carlson). More specifically, Taub, the main researcher responsible for the mistreatment of the monkeys was “charged with 15 accounts of animal cruelty” (Saperstein) Going back to the driving ideology behind the ALF’s actions—that a being’s rights are determined through legislation—by resorting to actions that resulted in legal punishment for researchers, the ALF reversed the roles, and threatened the rights of the researchers practicing on animals. In this case, however, researchers did not lose freedoms because of the belief that they were somehow inherently less deserving of them, but because their actions conflicted with the most important determinant of freedom—the law (Bentham 125). Because researchers lost freedom, and consequently the right to test on animals, the group directly targeted and deemed the Huntingdon Life Sciences powerless. Once again, the ALF’s ideology led to direct action, which in turn, not only infringed on the powers of researches, but also subverted the mainstream understanding of rights within society.

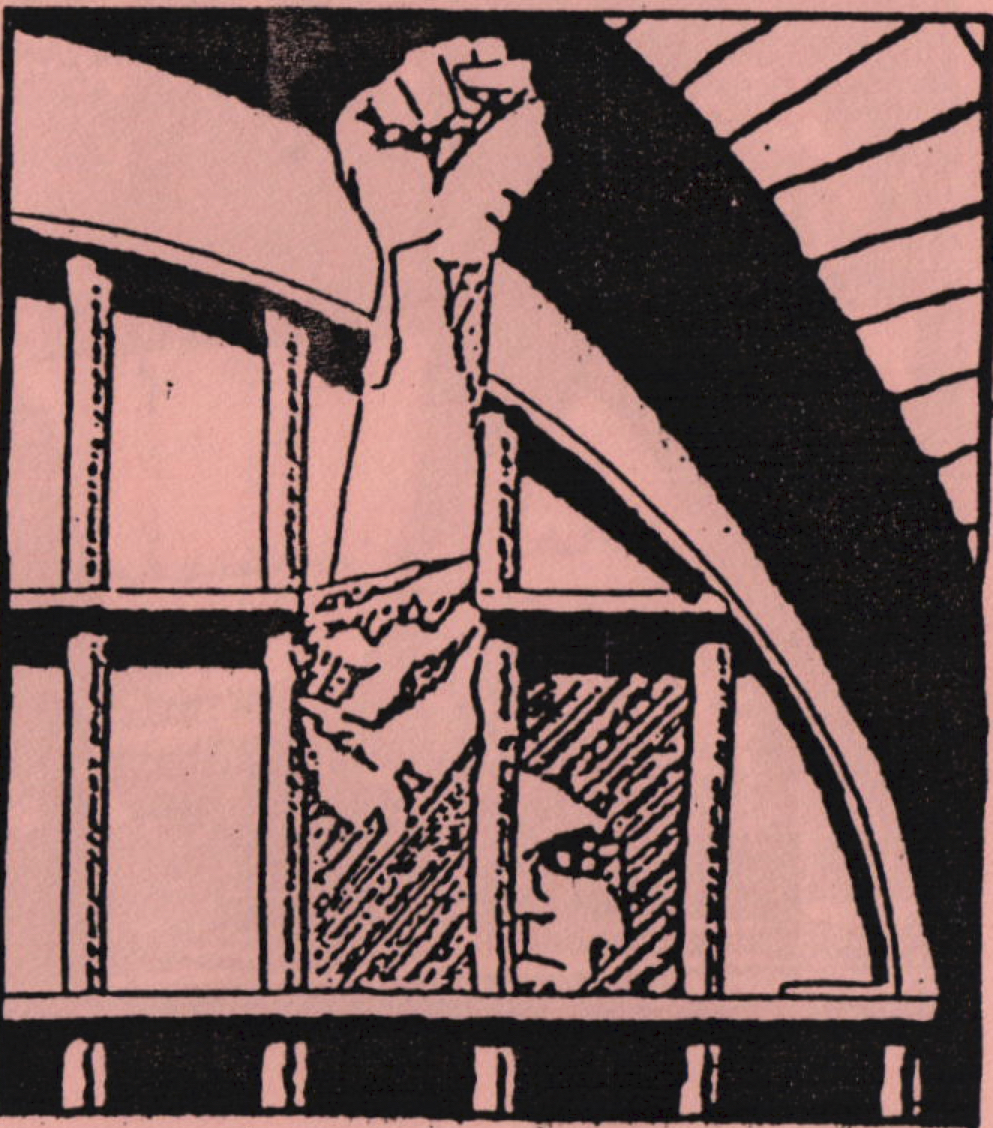

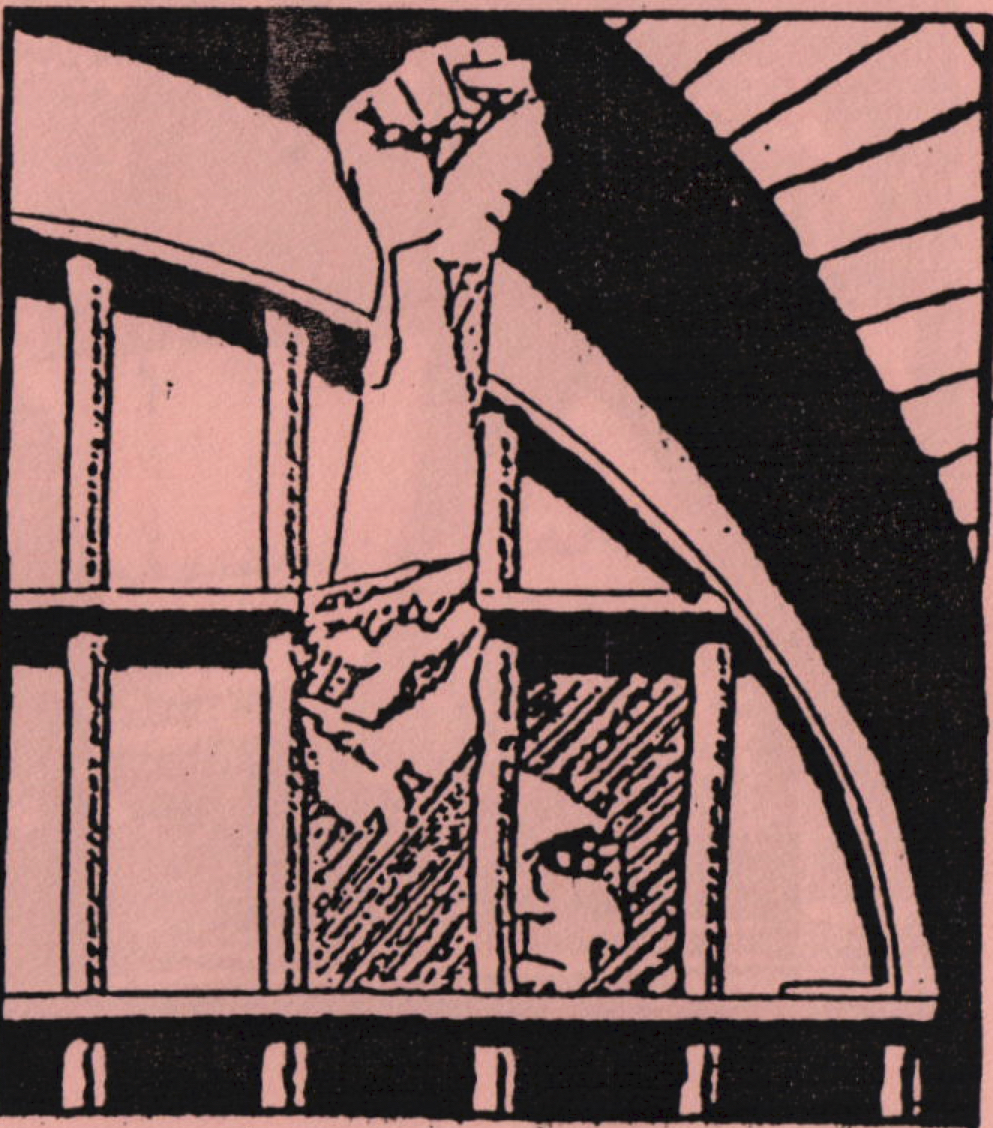

Not only did the ALF use direct action to subvert the culture industry, but it also subverted traditional power structures through its decision to act without a centralized hierarchy. With no formalized communications between its various sub-groups, the ALF acknowledged that, “any people … who carry our actions … have the right to regard themselves as part of the ALF” (Animal Liberation Primer). In addition to rejecting hierarchy in their pamphlet, the also published a striking image of a single fist raised, protruding through the bars of a jail cell. Not only does the fist in the image represent the ALF’s emphasis on unity, solidarity, and support, but it also demonstrates its defiance of the rigid and oppressive traditional power structures represented by the jail bars. Returning to their core ideology that there should be no hierarchy of species based on inherent or intrinsic qualities, the ALF modelled the very structure of their group after this idea. Since Peter Singer’s definition of speciesism rejects that individuals should be ranked or given more rights based on their ability to communicate or express themselves (Singer 8), the ALF refused to establish leaders or official titles within its various sub-groups. They further enforced this structure when they claimed all that matters is that people act, “by whom is not important” (Singer 9). By establishing that all members are equally valued, the ALF subverted mainstream society’s tendency not only to rank inter species, but intra-species as well. Not only did this structure subvert mainstream understandings of hierarchy, but it also made it harder for existing power structures, like law enforcement, to catch them. In the pamphlet, the ALF stressed the importance of “closely knit” and secretive sections in order for their actions to be difficult to trace (Singer 4). Without any established leaders to target, meetings to shut down, or hierarchies to disassemble, police had a significantly harder time tracking down members to jail and prevent from committing further acts of liberation. Thus, not only did this structure subvert common understandings of hierarchy, but it also allowed for the group to continue acting directly without interjection from the police.

Not only did the ALF use direct action to subvert the culture industry, but it also subverted traditional power structures through its decision to act without a centralized hierarchy. With no formalized communications between its various sub-groups, the ALF acknowledged that, “any people … who carry our actions … have the right to regard themselves as part of the ALF” (Animal Liberation Primer). In addition to rejecting hierarchy in their pamphlet, the also published a striking image of a single fist raised, protruding through the bars of a jail cell. Not only does the fist in the image represent the ALF’s emphasis on unity, solidarity, and support, but it also demonstrates its defiance of the rigid and oppressive traditional power structures represented by the jail bars. Returning to their core ideology that there should be no hierarchy of species based on inherent or intrinsic qualities, the ALF modelled the very structure of their group after this idea. Since Peter Singer’s definition of speciesism rejects that individuals should be ranked or given more rights based on their ability to communicate or express themselves (Singer 8), the ALF refused to establish leaders or official titles within its various sub-groups. They further enforced this structure when they claimed all that matters is that people act, “by whom is not important” (Singer 9). By establishing that all members are equally valued, the ALF subverted mainstream society’s tendency not only to rank inter species, but intra-species as well. Not only did this structure subvert mainstream understandings of hierarchy, but it also made it harder for existing power structures, like law enforcement, to catch them. In the pamphlet, the ALF stressed the importance of “closely knit” and secretive sections in order for their actions to be difficult to trace (Singer 4). Without any established leaders to target, meetings to shut down, or hierarchies to disassemble, police had a significantly harder time tracking down members to jail and prevent from committing further acts of liberation. Thus, not only did this structure subvert common understandings of hierarchy, but it also allowed for the group to continue acting directly without interjection from the police.

Still, there is no denying that to many, the ALF ineffectively subverted mainstream society because of the extremity of their acts. In fact, researchers put off by the ALF’s many break-ins deemed their actions to be, “antithetical to the concept of social discourse” (Holden) and took the initiative to defend animal testing more adamantly in response. What these researchers failed to acknowledge, however, is that in order for subversion to be effective, extreme actions are not only helpful, but imperative. In fact, Antonio Gramsci elaborates on this idea and claims that subversion can only be achieved through negation and “negative, polemic attitude” (Gramsci 271). Essentially, in order for consciousness to arise within a society, there needs to be the presence of opposition, tension, and polarity amongst thought and action. The ALF expanded on the importance of juxtaposition through the art they use in their pamphlet. Labeled, “It’s not the cat who needs his head examined” (Animal Liberation Primer 2), the ALF included a black and white cartoon of researchers standing over a cat whose head is connected to wires. The first observation that strikes the viewer is the stark contrast of the cartoon’s shading—while the cat is mainly white, the researchers that stand over it are etched with wrinkles that are intensely shaded in. The juxtaposition of lightness and darkness, seemingly symbolizing good and evil, helps to convey the message that researchers are not morally justified in their decisions to test on animals. Just as polar opposites help convey an artistic message in the pamphlet, similarly, extreme and polar actions in real life help individuals better understand the flaws within their society, Thus, although many criticized their extremism, it was essential that the ALF used bold actions to be able to formulate the ideology that fueled their subversion.

Still, there is no denying that to many, the ALF ineffectively subverted mainstream society because of the extremity of their acts. In fact, researchers put off by the ALF’s many break-ins deemed their actions to be, “antithetical to the concept of social discourse” (Holden) and took the initiative to defend animal testing more adamantly in response. What these researchers failed to acknowledge, however, is that in order for subversion to be effective, extreme actions are not only helpful, but imperative. In fact, Antonio Gramsci elaborates on this idea and claims that subversion can only be achieved through negation and “negative, polemic attitude” (Gramsci 271). Essentially, in order for consciousness to arise within a society, there needs to be the presence of opposition, tension, and polarity amongst thought and action. The ALF expanded on the importance of juxtaposition through the art they use in their pamphlet. Labeled, “It’s not the cat who needs his head examined” (Animal Liberation Primer 2), the ALF included a black and white cartoon of researchers standing over a cat whose head is connected to wires. The first observation that strikes the viewer is the stark contrast of the cartoon’s shading—while the cat is mainly white, the researchers that stand over it are etched with wrinkles that are intensely shaded in. The juxtaposition of lightness and darkness, seemingly symbolizing good and evil, helps to convey the message that researchers are not morally justified in their decisions to test on animals. Just as polar opposites help convey an artistic message in the pamphlet, similarly, extreme and polar actions in real life help individuals better understand the flaws within their society, Thus, although many criticized their extremism, it was essential that the ALF used bold actions to be able to formulate the ideology that fueled their subversion.

Through the rejection of common beliefs in their ideology, their direct actions, and their impact on the culture surrounding animal testing, the Animal Liberation Front was an effectively subversive group. Through challenging mainstream understandings of utilitarianism, suffering, and rights, the ALF argued for a society that not only considers the lives of animals, but also actively questions its hierarchal, moral, and ethical systems. In today’s world, we are often presented with the dichotomy of increased technology pushing for testing on animals and on the contrary, various movements, whether environmental or pro-animal, pushing for the rise of veganism. Through the ALF’s evaluation of animal rights and the complex establishments behind them, everyday citizens are forced to question and better understand their obligations and responsibilities towards the liberation and protection of non-humans.

Works Cited

Addley, Esther. “Animal Liberation Front Bomber Jailed for 12 Years: Victim Was Left Living in State of Fear, Court Told Conviction Devastating Blow to Extremists.” The Guardian, 8 Dec. 2006. link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/A155643731/STOM?sid=lms. Accessed 16 Nov. 2019.

An Animal Liberation Primer, Second Edition. Internet Archive, n. d. archive.org/details/AnAnimalLiberationPrimerSecondEdition. Accessed 16 Nov. 2019.

“Animal Liberation Front Attacks Huntingdon Life Sciences Supplier.” 24 Jul. 2009. Animalliberationpressoffice.org/NAALPO/2009/07/24/animal-liberation-front-attacks-huntingdon-life-sciences-supplier/.

Accessed 17 Nov. 2019.

Benthall, Jonathan. “Animal Liberation and Rights.” Anthropology Today vol. 23, no. 2 (2007): 1–3. doi.org/10.1093/oseo/instance.00077240. Accessed 17 Nov. 2019.

Bentham, Jeremy. “An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation,” edited by J. H. Burns and H. L. A. Hart. The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham, edited by F. Rosen and Philip Schofield. Oxford UP, 1996.

Brown, Jonathan. “Animal Rights Militant Admits Bomb Offences.” The Independent, 22 Sep 2011. independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/animal-rights-militant-admits-bomb-offences-412366.html. Accessed 18 Nov. 2019.

Carlson, Peter. “The Great Silver Spring Monkey Debate.” Washington Post, 24 Feb. 1991. washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/magazine/1991/02/24/the-great-silver-spring-monkey-debate/25d3cc06-49ab-4a3c-afd9-d9eb35a862c3/. Accessed 17 Nov. 2019.

Cohen, Carl. “The Case for the Use of Animals in Biomedical Research.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 315, no. 14, 1986, pp. 865-70.

Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. Translated by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. International Publishers, 2014.

Holden, Constance. “Animal Rightists Threaten Researcher.” Science 247, no. 4941 (1990): 407–407.

Horkheimer, Max, and Theodor W. Adorno. “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception.” Dialectic of Enlightenment. Herder and Herder, 1972.

Singer, Peter. Animal Liberation, New Revised Edition. Avon, 1975. Internet Archive. archive.org/details/animalliberation00sing_0. Accessed 28 Nov. 2019.

Saperstein, Saundra. “The Monkeys: A Rally for Animal Lovers: Montgomery’s Monkeys: A Rally for the Nation’s Animal Lovers.” Washington Post, 11 Oct. 1981.

About This Paper

Expand All

RESEARCH PAPER

The research essay builds on previous essays because you will use multiple lenses and close readings to make an argument. For this essay, find a news story that talks about one of the following “subversive” groups listed below. The news story will be your primary text, and it should address either a specific action by the group, or refer to its contemporary influence. After identifying and researching the major issue (for example, the 2008 ELF arson of Seattle Street of Dreams) make an argument about the form of subversion practiced by the group, its effectiveness, and its influence more broadly on political, social and popular culture. You are encouraged to choose a group that you know little about so that your argument will be informed by your research. You will be doing a close reading of the article that uses outside research (at least four scholarly sources, with at least one framing source) to bolster your argument. The library has plenty of resources on any of the older groups, and I am happy to recommend some sources as well (as a last resort) on newer groups. This activity is meant to help you learn some of your own research skills. You are welcome to suggest your own group or event pending approval.

- The Situationists — You might be interested in the historical phenomenon that was the Situationist International. The Spectator Online has an article, “How the Situationists Changed History.” That would provide a good starting point for evaluating whether they did change history.

- Act Up! — One of the first major gay rights and HIV advocacy groups. ACT UP! Employed many novel forms of protest that are worth exploring; grievance, direct action, shock tactics, reclaiming (redefining) sexual permissiveness.

- Black Panther Party — There are many sources on the Black Panther Party outside of Malcolm X that are worth exploring. Their militancy and actions added a new dimension to civil rights advocacy that deviated significantly from the non-violence. You might also focus on women in the party, or former members’ current role in the public sphere.

- Red Army Faction (Baader-Meinhof Gang) — The RAF was an organization that formed to combat the influence of former Nazis in German politics. They were a group defined by their actions, so you could explore how effective their actions were, and whether they have any influence today.

- Ku Klux Klan — A white supremacist organization that has re-appeared in American history since the end of the Civil War. You could use a contemporary news story of the Klan or Klan member in order to answer how the organization has endured, paying attention to ideology and recruitment.

- The Weather Underground—A domestic terrorist organization responsible for bombings and jail breaks, primarily in the Midwest. One of its former members went on to be an academic (Bill Ayers) so it might be useful to examine the Weathermen’s influence through him or their news coverage.

- Black Mask/Up Against the Wall Motherf**ker — An anarchist organization based out of New York City influenced by Dadaism and other forms of avant-garde art. They are believed to be in some way responsible for the murder of Andy Warhol. If you chose this, you could write about their tactics and propaganda, which are published collectively in a book by PM Press.

-

Black Lives Matter — One of the newer groups to emerge from issues of police brutality, BLM employ a variety of tactics to make their voice heard. They have also given rise to an antithesis group, “Cop Lives Matter,” perhaps throwing the efficacy of their project into disarray.

-

Antifa — Following the Charlottesville protests in the summer of 2017 Antifa re-emerged into popular American discourse. Formally a group known more in Europe around soccer culture, disjointed sects of Antifa have appeared in just about every major city in the United States since. A paper on them might look at some of their recent actions, evaluating how their subversive protests push the limits of acceptable political action.

-

Alt-Right — The alt-right is another affiliation that has recently emerged in American political discourse. Like their anti-fascist counterparts, they employ a variety of unorthodox tactics to get their message across. A paper on the alt-right might follow some of their protest actions to evaluate the ways they are trying to challenge or overturn cultural and social orthodoxy, carving out a place for “rightist” subversion. (You can also narrow in on a particular alt-right affiliated group, like the Proud Boys).

-

Animal Liberation Front — The ALF is an active protest group that can often be seen in public streets in urban centers. They also employ unorthodox protest tactics. You could use an article about an ALF action to question whether their form of subversion has been effective.

-

Other possibilities: Time’s Up, Standing Rock, Woman’s Marches, Yellow Vests.

YOU MAY ALSO CHOOSE A GROUP TO WRITE ABOUT PENDING MY APPROVAL.

Once you have a group picked out, begin to think about why the group is considered subversive, and what types of actions it committed, and whether the tactics were effective in the long run. One effective strategy for finding your primary text news article is to search for the group in Google under the “News” category and see what comes up, where they are mentioned, etc. You are welcome to use the groups listed above for your research topic, but you can also chose another group with my approval. You will spend a lot of time on this essay, so find something that truly interests you! Regardless of what you choose, you must find and print out a news story about your group that addresses the its actions and influence.

The most successful essays will have close reading of the case and engage with counterarguments, thus demonstrating that this is a nuanced issue with more than two sides.

For your research you must use a minimum of four sources (your case does not count as a research source). Your research should come from reputable, peer-reviewed publications. In addition you must use Adorno or Gramsci as one of your frames for understanding subversion. Consider whether your topic uses multiple forms of subversion (political, cultural, social, etc) and think about how to address that.

This will be the longest and most time-consuming paper of the semester and will thus require significant preparation and thought. You will be developing your own interpretive framework based on the scholarly work of others. This resembles lens analysis — you’ll be using others’ ideas to produce an informed reading of your argument — but with an important difference: here, you’ll be creating a new lens of your own making, one that borrows elements from, reacts against, and synthesizes multiple lenses into an original critical stance. Be sure to locate sources that both agree and disagree with your claims so that you can anticipate counter-arguments in your paper. Your paper should follow CHICAGO formatting guidelines.

Essay length: 10-12 pages. The first draft of the essay must be submitted electronically to your peers and me no later than 11:55 PM on Monday, April 15. Essays must use 1-inch margins and 12 point Times New Roman font. Do not enlarge your punctuation — I can tell. Essays must have a title, be double-spaced and have page numbers. Pre-drafts will be submitted in hard copy in class and must be typed and stapled.

GOALS OF THE ESSAY

In addition to continuing work on the goals of essays 1 and 2, this assignment asks you to:

- Integrate primary and secondary source material. You should not simply report the findings of your research, as you would in a literature review or book report, but incorporate them into your argument as evidence or motive. Remember, a quotation never speaks for itself — you must spell out its implications and relevance for your reader.

- Close with a conclusion that draws out the implications of your argument and shows where the process of the paper has taken us. Your essay should walk us through a developing process of thought, rather than offer an already-decided idea. Thus, your conclusion should show us where we end up after following the steps of your thought process—a different place than where you begin in your introduction. Remember: your motive brings you from the outside world into the writing space of your essay; it can help you find your way back out, too.

- Transition logically and smoothly from paragraph to paragraph and idea to idea. A transitional topic sentence does the double duty of 1) encapsulating the main idea of its paragraph, and 2) smoothly transitioning from the last idea of the previous paragraph. A topic sentence will ensure that each paragraph proves a specific claim and that your paper has an overall logical flow. Remember that transition occurs not only on the rhetorical level but also on the content level. Use signposting and reflection to help move your reader from one idea to the next and to show the developing thought process your essay records.

- Title your paper. Titles should be eye-catching — they’re the first opportunity you have to hook your reader—and informative, hinting at the overall focus and aim of your paper.

PRE-DRAFT 3.1: RESEARCH PAPER PLAN

A research paper plan serves a number of functions. It gives you a concrete starting place from which to depart and grow. It forces you to start writing early on. Most importantly, though, it helps you gauge what you currently know and what you need to discover about your subject. Plans also help to outline argumentative moves. Your plan should be 2 double spaced pages that address the following components:

- The topic of your research and the name of the group you will be researching. Also provide a brief summary of the group.

- A description of the forms of subversion that you plan to evaluate and why.

- A discussion of the conversation around your topic. What sort of news sites does the group appear in? At this point, what do you find most compelling or problematic?

- A brief discussion of any questions or problems you’re having at this point

- A list of the sources you’ve found

In addition, please fill out the following:

- Topic: I am studying: ________________________(i.e., how the holocaust changed the political views of Hungarian political prisoners)

- Conceptual Question: because I want to find out____________(i.e., how the holocaust and genocide changed their mindset)

- Conceptual Significance: in order to help readers understand_______ (i.e., how genocide impacts our understanding of the past and future)

- Potential Practical Application: so that readers might better gain a better understanding of __________________________(i.e., the significance this event has on history)

- Who is your audience? _______________________________

Finally, please attach a copy of the news article that you’ll be using as your primary source.

We will be conferencing about your plans rather than after the first draft, so the more information you provide the better the feedback that I can offer.

PRE-DRAFT 3.2

At this point, you’ve had almost two weeks to research your text and to review and select your sources. You are now prepared to submit an annotated bibliography. Your annotated bibliography (the format of which we’ve discussed in class) should include four or five secondary scholarly sources. Each entry should be followed by an annotation in paragraph form that gives the following information:

- Type of source (book, article, electronic etc…)

- The specific subject the author is writing about

- What the author seeks to discover, prove or challenge

- The broad debates the author seeks to discover, prove, or challenge.

- How the source will contribute to your research.

- Remember to follow CHICAGO BIBLIOGRAPHIC citation format carefully; I will be paying special attention to how you cite in this essay. Remember, too, that annotations both summarize and evaluate the importance of a source.

Sample Entry:

Research question: Is it immoral to eat beef?

Lappé, Francis Moore. Diet for a Small Planet. 2nd ed. New York: Ballantine, 1991.

This book was originally published as a pamphlet in the 70s—Lappé was researching the causes of world hunger and global food supply when her data led her discover that, in fact, the world made more than enough food to feed everyone. The problem was how that food—grains, nuts, etc. — was being used; much of it was being used ineffectively, and the people suffering were the poor and underrepresented. This book was groundbreaking in the way that it revealed the significance of food choices and the potential consequences of the American meat-based diet. Diet for a Small Planet has been one of the most influential pro-vegetarian arguments in American history. I plan on using the passage that describes the inefficiency of beef consumption: “For every 16 pounds of grain and soy fed to beef cattle in the United State,” Lappé writes, “we only get 1 pound back in meat on our plates.” The other fifteen pounds, she explains, are inaccessible as food sources (69).

Pre-Draft 3.3: Rough Draft Outline

As you did for the close reading and lens essays, you will write a comprehensive outline to ensure that your paper has a logical structure and evidence that is relevant to your argument. Again, each paragraph should have a separate claim that supports the thesis, as well as evidence and analysis. In order to organize your paragraphs you will have to select and analyze quotations. The argument should develop as the paper unfolds. In other words, paragraphs should not be interchangeable. The outline should follow the format below:

- Introduction

- Paragraph #1 (Background information)

- Topic Sentence

- Contextualization: For research paragraphs, name the author of the source, his or her credentials and the name of the source. For close reading paragraphs, tell the reader what is happening in the case study.

- Evidence: include the quotation and the page number

- Analysis: restate the quotation in your own words for research paragraphs or give a brief summary of how you plan to analyze the quotation.

- Relevance: a brief statement of how the evidence relates to your thesis

- Paragraph #2

- Topic Sentence

- Contextualization: For research paragraphs, name the author of the source, his or her credentials and the name of the source. For close reading paragraphs, tell the reader what is happening in the case study.

- Evidence: include the quotation and the page number

- Analysis: restate the quotation in your own words for research paragraphs or give a brief summary of how you plan to analyze the quotation.

- Relevance: a brief statement of how the evidence relates to your thesis

- Etc… for ALL of the body paragraphs. You should have a minimum of ten body paragraphs.

- Final paragraph: Conclusion — what are the larger implications of your argument? How does the text comment on a broader theme than just your specific claims?

POST YOUR OUTLINE TO LATTE BY 11:55 PM ON MONDAY, APRIL 8

Leeza Barstein discussed her paper with Write Now! editor Doug Kirshen and her UWS instructor, Alexander Herbert.

Leeza Bernstein and her instructor Alexander Herbert discussed her paper and the seminar with Write Now! editor Doug Kirshen.

Doug Kirshen: I'm here with Leeza Bernstein and with Alexander Herbert her UWS instructor to talk about her paper, "Suffering Redefined: The Animal Liberation Front's Subversion of Utilitarianism." I'm really excited to talk with you about that, but let me start with Alexander. Tell me about this UWS. What was your concept of it and what did you hope to get from this assignment?

Alexander Herbert: The concept of the class was the politics of subversion, and so we wanted to look at various groups throughout history, mostly US history. Even though I'm a European historian, I thought it would be more approachable for the average freshman to view this through American history, and so the idea was to get them to think about what a subversive group is. And you know to start thinking of ways of defining that, because a lot of Brandeis students in particular are exposed to radical groups. We have [Brandeis alumna] Angela Davis [for example], who has a lot of people talk about her. Black Lives Matters is a major group right now. So my idea was to try to get them to think about these groups in a historical context and also an analytic context to try to understand them more.

Doug Kirshen: One of the lenses Leeza used was Jeremy Bentham's text on utilitarianism. Can you tell us briefly about that?

Alexander Herbert: I think that that was actually a text that Leeza found on her own. Which, which is another reason why her paper was impressive for me was because the two main lens texts that I used were [Antonio] Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks. He has a section on subversive politics. And then Horkheimer and Adorno, "The Culture Industry," and these two texts are already very difficult to engage with. I went through a whole class going through each one of these.

Doug Kirshen: So Leeza, let me ask you what attracted you to this topic. Why did you choose to write about the Animal Liberation Front?

Leeza Barstein: I've always been interested in animal rights. In high school I was involved in some organizations that worked with local animal shelters. And my sophomore year, I had the opportunity to do a research project on animal testing policy in the United States and that kind of changed my personal consumption habits. So I thought it would be cool to continue working with my interests but viewing it from a more radical lens.

Doug Kirshen: Had you heard of the ALF before this class, and did you know anything about what they did?

Leeza Barstein: No, I didn't know anything about the ALF. We talked about the Earth Liberation Front in class, so that was kind of a guide when I was learning about the ALF, because they have a similar tactics and approaches to their activism, but before the class I didn't know anything about them.

Doug Kirshen: How did you get started writing this? Was it difficult to get rolling, or did you jump right in? How did it go at the beginning?

Leeza Barstein: One of our first assignment was to find a news article that had to do with the organization that we picked, and so I found a compilation of news clippings from the 80s and 90s that involved the ALF, and some of them had anonymous interviews with members, so that was really helpful. I also, it was kind of difficult at first, because since the organization's kind of decentralized, there wasn't like a singular website that I could go to that could explain what they were doing, but Alexander helped me with finding a pamphlet about the ALF and he also recommended that I read Animal Liberation by Peter Singer, which was really helpful, and learning what's speciesism is and better understanding the concept of a hierarchy of species that I talked about in my paper.

Doug Kirshen: Do you recall what it was like to go through the draft process and peer review and talking about it with Alexander? What do you remember about the process here?

Leeza Barstein: I think I relied a lot on the previous papers we wrote and the sources that we used in class. We started this semester meeting Dostoevsky’s Underground Man [Notes from Underground], and that was really helpful in understanding a general idea of what it means to be subversive. Like I said earlier, we talked about the ELF, which was really helpful specifically for my paper because the two groups are really similar. We read Adorno and Gramsci in class in relation to the punk movement. Reading that together really helped me a lot, when I was writing my paper, so I kind of felt like I had like a collection of quotes and ideas that I already wanted to use, and then I think the peer review process is really helpful for me, because it helps me see where I wasn't being clear.

Doug Kirshen: Do you recall if your ideas changed as you were in the course of writing this? Did you have any "aha" moments? Or did you find yourself thinking about the topic differently when you finished than when you began?

Leeza Barstein: My definition of "subversive" changed as I was writing because I started off mostly talking about ideology, focusing on the pamphlet and interviews with members. But as I started reading more about their economic warfare and the direct action they were doing, I realized that subversion had a lot more to do with the direct action and the subsequent change that follows. So I would say, as I was writing, I kept tweaking my definition of what it means to be subversive.

Doug Kirshen: That's great. So you kept evolving your definition of what it means to be subversive, and you would go back and apply that and develop that further. Alexander, how did your students in general respond to this assignment? What were you hoping to get from them, and what did you get?

Alexander Herbert: I wanted to get exactly what Leeza said, which is develop an understanding of subversion that was based on the course material, but then also — I believe that these things have your own opinions and definitions also inflected in them. So, for example, one lecture that we went through was on the on the term "terrorism" and how it can apply to groups like the ALF and stuff like that, and there were some students who were adamantly opposed to the sort of environmental terrorism that the ELF engaged in, and then there were other students who were sympathetic to it and didn't consider it to be terrorism in the commonly used sense. So really what I was trying to get from them was to articulate their own definition, and then that definition that they came up with by design would also sort of serve as their thesis statement. It was really easy to take that definition and tweak it into your argument for the paper, this is how your group is subversive.

Doug Kirshen: What did Leeza specifically do well?

Alexander Herbert: Leeza's paper integrated both the course material and then went the extra mile by finding other sources outside of the class, which demonstrated that she had actually not just read the material from the course and understood it, but also pulled out the main threads of all that work and was able to supplement it with things that if I had covered the ALF I would have used myself. So it demonstrated a more comprehensive understanding of the whole class. It's also really well organized. Something that I went through a lot with the students is organizing papers and how to make sure that your paper is organized and has a clear thesis statement. This idea of a thesis comes naturally to a lot of people and to others it's really hard to grasp. So I spent maybe two classes going over weaker and stronger theses, talking about what is a good thesis and what is less good.

Doug Kirshen: Leeza, tell me anything else you'd like to say about this project and what advice you might have for future students.

Leeza Barstein: I would say that using other materials from the class and relying a lot on the feedback from previous papers is a really good idea. I incorporated a lot of the aspects from the close reading paper and from the lens paper into my research paper, and so I already had a lot of feedback from Alexander and from my peers in the class, so just applying those to my paper helped me get a lot stronger.

Doug Kirshen: Do you think you took any chances in this paper? Did you feel like you were risking anything by going out on your own as Alexander said?

Leeza Barstein: Yeah in some ways, I guess. One of the counterarguments I brought up in the paper was that a lot of people saw that their [the ALF’s] acts were terrorist acts, and I think a lot of people in class thought that as well, and so I would say the stance I took on it — sometimes I was kind of doubting it. I'd say that was like the biggest chance I took.

Doug Kirshen: I think you took a very fair and objective stance in your paper, and it was fascinating to read about this group and your analysis of it. Any last words?

Alexander Herbert: I would also just add to what made Leeza's paper and others really successful is that built into the class was that if students get to a point where they start finding sympathies with groups that we branded as terrorists, then the student themselves are committing an act of subversion. So this sort of kind of mind-play was built into the course, of getting students to think twice about this sort of stuff, and Lisa demonstrated that perfectly.

Doug Kirshen: Well, thank you both very much for talking with me today.

Not only did the ALF use direct action to subvert the culture industry, but it also subverted traditional power structures through its decision to act without a centralized hierarchy. With no formalized communications between its various sub-groups, the ALF acknowledged that, “any people … who carry our actions … have the right to regard themselves as part of the ALF” (Animal Liberation Primer). In addition to rejecting hierarchy in their pamphlet, the also published a striking image of a single fist raised, protruding through the bars of a jail cell. Not only does the fist in the image represent the ALF’s emphasis on unity, solidarity, and support, but it also demonstrates its defiance of the rigid and oppressive traditional power structures represented by the jail bars. Returning to their core ideology that there should be no hierarchy of species based on inherent or intrinsic qualities, the ALF modelled the very structure of their group after this idea. Since Peter Singer’s definition of speciesism rejects that individuals should be ranked or given more rights based on their ability to communicate or express themselves (Singer 8), the ALF refused to establish leaders or official titles within its various sub-groups. They further enforced this structure when they claimed all that matters is that people act, “by whom is not important” (Singer 9). By establishing that all members are equally valued, the ALF subverted mainstream society’s tendency not only to rank inter species, but intra-species as well. Not only did this structure subvert mainstream understandings of hierarchy, but it also made it harder for existing power structures, like law enforcement, to catch them. In the pamphlet, the ALF stressed the importance of “closely knit” and secretive sections in order for their actions to be difficult to trace (Singer 4). Without any established leaders to target, meetings to shut down, or hierarchies to disassemble, police had a significantly harder time tracking down members to jail and prevent from committing further acts of liberation. Thus, not only did this structure subvert common understandings of hierarchy, but it also allowed for the group to continue acting directly without interjection from the police.

Not only did the ALF use direct action to subvert the culture industry, but it also subverted traditional power structures through its decision to act without a centralized hierarchy. With no formalized communications between its various sub-groups, the ALF acknowledged that, “any people … who carry our actions … have the right to regard themselves as part of the ALF” (Animal Liberation Primer). In addition to rejecting hierarchy in their pamphlet, the also published a striking image of a single fist raised, protruding through the bars of a jail cell. Not only does the fist in the image represent the ALF’s emphasis on unity, solidarity, and support, but it also demonstrates its defiance of the rigid and oppressive traditional power structures represented by the jail bars. Returning to their core ideology that there should be no hierarchy of species based on inherent or intrinsic qualities, the ALF modelled the very structure of their group after this idea. Since Peter Singer’s definition of speciesism rejects that individuals should be ranked or given more rights based on their ability to communicate or express themselves (Singer 8), the ALF refused to establish leaders or official titles within its various sub-groups. They further enforced this structure when they claimed all that matters is that people act, “by whom is not important” (Singer 9). By establishing that all members are equally valued, the ALF subverted mainstream society’s tendency not only to rank inter species, but intra-species as well. Not only did this structure subvert mainstream understandings of hierarchy, but it also made it harder for existing power structures, like law enforcement, to catch them. In the pamphlet, the ALF stressed the importance of “closely knit” and secretive sections in order for their actions to be difficult to trace (Singer 4). Without any established leaders to target, meetings to shut down, or hierarchies to disassemble, police had a significantly harder time tracking down members to jail and prevent from committing further acts of liberation. Thus, not only did this structure subvert common understandings of hierarchy, but it also allowed for the group to continue acting directly without interjection from the police.  Still, there is no denying that to many, the ALF ineffectively subverted mainstream society because of the extremity of their acts. In fact, researchers put off by the ALF’s many break-ins deemed their actions to be, “antithetical to the concept of social discourse” (Holden) and took the initiative to defend animal testing more adamantly in response. What these researchers failed to acknowledge, however, is that in order for subversion to be effective, extreme actions are not only helpful, but imperative. In fact, Antonio Gramsci elaborates on this idea and claims that subversion can only be achieved through negation and “negative, polemic attitude” (Gramsci 271). Essentially, in order for consciousness to arise within a society, there needs to be the presence of opposition, tension, and polarity amongst thought and action. The ALF expanded on the importance of juxtaposition through the art they use in their pamphlet. Labeled, “It’s not the cat who needs his head examined” (Animal Liberation Primer 2), the ALF included a black and white cartoon of researchers standing over a cat whose head is connected to wires. The first observation that strikes the viewer is the stark contrast of the cartoon’s shading—while the cat is mainly white, the researchers that stand over it are etched with wrinkles that are intensely shaded in. The juxtaposition of lightness and darkness, seemingly symbolizing good and evil, helps to convey the message that researchers are not morally justified in their decisions to test on animals. Just as polar opposites help convey an artistic message in the pamphlet, similarly, extreme and polar actions in real life help individuals better understand the flaws within their society, Thus, although many criticized their extremism, it was essential that the ALF used bold actions to be able to formulate the ideology that fueled their subversion.

Still, there is no denying that to many, the ALF ineffectively subverted mainstream society because of the extremity of their acts. In fact, researchers put off by the ALF’s many break-ins deemed their actions to be, “antithetical to the concept of social discourse” (Holden) and took the initiative to defend animal testing more adamantly in response. What these researchers failed to acknowledge, however, is that in order for subversion to be effective, extreme actions are not only helpful, but imperative. In fact, Antonio Gramsci elaborates on this idea and claims that subversion can only be achieved through negation and “negative, polemic attitude” (Gramsci 271). Essentially, in order for consciousness to arise within a society, there needs to be the presence of opposition, tension, and polarity amongst thought and action. The ALF expanded on the importance of juxtaposition through the art they use in their pamphlet. Labeled, “It’s not the cat who needs his head examined” (Animal Liberation Primer 2), the ALF included a black and white cartoon of researchers standing over a cat whose head is connected to wires. The first observation that strikes the viewer is the stark contrast of the cartoon’s shading—while the cat is mainly white, the researchers that stand over it are etched with wrinkles that are intensely shaded in. The juxtaposition of lightness and darkness, seemingly symbolizing good and evil, helps to convey the message that researchers are not morally justified in their decisions to test on animals. Just as polar opposites help convey an artistic message in the pamphlet, similarly, extreme and polar actions in real life help individuals better understand the flaws within their society, Thus, although many criticized their extremism, it was essential that the ALF used bold actions to be able to formulate the ideology that fueled their subversion.