Disney’s Frontierland Fantasy

How the Free Market Fabricates the Wild West

Izzy Dupré

Lens Paper | UWS 53b Mythology of the American West | Eric Hollander | Fall 2021

About this paper | This paper as PDF | Chicago format

To all who come to this happy place; welcome. Disneyland is your land. Here age relives fond memories of the past…and here youth may savor the challenge and promise of the future. Disneyland is dedicated to the ideals, the dreams and the hard facts that have created America…with the hope that it will be a source of joy and inspiration to all the world.

— Walt Disney[1]

Wedged between Disneyland’s Sleeping Beauty Castle and a Star Wars spaceship, a themed land invites guests from across the globe to explore America’s famous Wild West: Frontierland. Although the Walt Disney Company, an entertainment conglomerate worth billions of dollars, has developed new attractions across its multiple amusement parks, Walt Disney’s original Frontierland, a place dedicated to the American trailblazers of the nineteenth century, still stands as a foundational piece of the self-proclaimed Happiest Place on Earth. After stepping off a stagecoach, steamboat, or railroad and into a mine, tavern, or rodeo, visitors can embrace the life of a cowboy. However, such spectacles exclude the harsh realities of nineteenth-century expansion into the American West, and instead focus on drawing in folks’ eyes — and wallets—with cartoonish figures, merchandise, and performances. By romanticizing the brutalities on which the nation was formed, Walt’s version of the West fixates on capitalist priorities, similarly to how early settlers pursued economic opportunities. In fact, Walt Disney had to act as a pioneer himself to actualize his vision of this idealized America, one open only to those who can afford the price of a ticket. His industrial spirit inspired a business that pleases people for profit, and in doing so fantastically mythologizes the Old West.

Just like westward expansion, Disney parks continue to grow, as attractions like Frontierland monetize the nation’s manipulated memories. What is the appeal of a fake frontier, and why do consumers still devote time, energy, and money to being a part of one? Despite their differences, the true West and Disney’s Frontierland both reflect America’s commercial drive. With capitalists reigning as today’s cowboys and the free market replacing the frontier, Disney’s Frontierland glamorizes American expansion and thrives while doing so because the nation has centered its identity around dreams as wild as the West.

Examining the profitability of the Disney park for pioneers requires an understanding of what a frontier, a free market, and a theme park represents. While academics debate the nuances surrounding these concepts, base definitions will contribute worthy context. Many scholars have noticed that Walt Disney’s writings “reveal a Turnerian view,” referring to the Frontier Thesis of Frederick Jackson Turner. In his seminal essay, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” first published in 1893, Turner presents the frontier as “the meeting point between savagery and civilization” and “the formation of a composite nationality for the American people,” thus presenting the frontier as a social transformation rather than a physical place. The land beyond boundaries, the frontier thus symbolizes the bold spirit of America, a nation Turner considers “another name for opportunity.”[2] Turner ties lands of possibility to his people’s resourceful culture, alluding to the significance of capitalism, which historian David M. Wrobel calls “essential to understanding power, influence, and change in the American West.”[3] Indeed, even the earliest settlers, the Pilgrims, came to the country with economic motivations, so expansion into the West reflected America’s focus on capitalism from its very beginning as a nation.[4] Explaining this force, historian Immanuel Wallerstein asserts, “virtually everyone tends to see capitalism as the system in which humans seek to transform (or ‘conquer’) nature in an eternally expansive way” to highlight the exploitive processes enterprisers must perform on the outer world for individual success. [5] For further emphasis, Max Weber confirms, “a man exists for his business, and not the other way around” [6] when pursuing such entrepreneurial feats, like the establishment of Walt Disney’s self-titled empire.

Much of Disney’s business depended on theme parks, and Disney designer Joe Rohle described themes as “the philosophical premise[s] that drive the storyteller to tell the story,” connecting Walt Disney’s identity to his industry.[7] While Disney committed himself to creating magical experiences, scholars have scrutinized the transactional demands of amusement parks in assessing that these lands “have much more to do with the global order of advanced corporate and consumer capitalism than with any national cultural identities.”[8] In promoting his themes, narratives motivated by entrepreneurship, to the new majority middle class of the 1950s, Disney prioritized prosperity in building Disneyland. So, the Turnerian promotion of capitalism, the free market’s ever-consuming impact, and the theme park’s immersive commercialization all relate to Walt Disney and his creation of Frontierland. The icon’s own life molded the messaging of his Frontierland, and thus merits additional analysis.

Disney, a figure as revered as the cowboy, invested in his vision of a fantasy world because he shared the values of the pioneers, icons he viewed as forefathers of the nation, including those who first profited from the soil of the site where Frontierland would be built. Born in 1901, Disney grew up upon the end of American expansion, so migrations like the Gold Rush shaped the lives of his forbearers. The Gold Rush, which has been regarded as “the consolidation of American capitalism,” brought more than 300,000 settlers to California and generated about $550 million by end of the 1850s. Yet only a select few prospered; “ninety-nine out of a hundred men in the California placer diggings were lucky to make expenses.”[9] Though “capitalist interests were involved in colonial adventures in North America from the start,” the Gold Rush especially established “a rootless, chaotic, and impersonal world driven entirely by the search for money,” exposing the nation’s enterprising roots.[10] From the first colonials to the migrating miners, those who defined American expansion — and the myths later attached to the movement — found their motivation in the idea of prosperity. Lured by outlandish opportunities, the mass of hopefuls that trekked to California bear resemblance to Walt Disney, who would later follow his visions in the very same state. Pioneers therefore instilled his inherent industrialism, especially as he learned to navigate the lands previously explored by his role models. Disney stressed this relation himself in True West magazine when he admitted that, out of all of his themed places, “Frontierland evokes a special response because it reminds me of my youthful days on the Missouri.”[11] Impoverished in a stereotypical southern setting, Disney idealized the West from an early age because it matched the conditions of his own life. His praise for people like Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone was rooted in nostalgia, and he reveals this motivation by expressing that “the fact that many such heroes covered the same ground I knew in Missouri made them all the more real to me.”[12] Although these explorers existed, Disney’s use of the label “hero” and his emphasis on their relatability suggests that he glorified rustic role models and molded his motivations around childhood fantasies. Considering that he risked his production company, his personal finances, his bank loans, and even his life insurance collateral in funding Disneyland, Walt Disney truly chased his visions as boldly as the authentic gold rushers and the frontiersmen of folklore.[13] Disney himself attached his park to his cowboy customs in the opening day speech for Disneyland, a realm he “dedicated to the ideals, the dreams and the hard facts which have created America, with the hope that it will be a source of joy and inspiration to all the world.”[14] By honoring “dreams” and “facts” in the same statement, he implies that all Americans can materialize their wishes just as he did as an unlikely success, although the brutal reality of the Gold Rush demonstrates otherwise. He presents his message through a patriotic lens, but hints at the globalization of his virtues as well, evoking the energy of American expansion. Walt Disney only dared to monetize his dreams because of the western whimsies that engulfed his youth. He built Frontierland, the place representing his background, on the same fantasies that filled his pockets. When brought to life, legends can manipulate the masses, especially when their fictions present themselves as facts.

Disney engineered Frontierland to appear authentic yet appealing to his audience, and in doing so promoted a narrowed perspective that shielded the county’s middle class from dark realities of the West. Etched into a plaque, Walt Disney’s own words still uphold his self-designed Wild West:

Here we experience the story of our country’s past . . . the colorful drama of Frontier America in the exciting days of the covered wagon and the stagecoach. . . the advent of the railroad . . . and the romantic riverboat. Frontierland is a tribute to the faith, courage and ingenuity of the pioneers who blazed the trails across America.[15]

The biggest section of the park upon opening day, Frontierland looked legitimate yet offered a cartoonish experience from the beginning, as Walt’s dedication highlights with descriptors like “colorful,” “exciting,” and “romantic.” The hands-on nature of the activities available in this particular site convinced guests that they really could understand the cowboy lifestyle by riding a wagon, stage coach, railroad, steamboat, or even one of the live pack mules. Nature’s Wonderland, a wilderness guests could admire from the Rainbow Caverns mine train, further exacerbated this blend of accuracy and fallacy, which Vacationland, a Disney publication, reveals in an article about the $1.8 million “faithful recreation” with a cast of “204 animated and amazingly realistic animals.”[16] The article contradicts itself as it stresses the realism of fake sights while highlighting attractions akin to wonderlands and rainbows, images one could find on a storybook cover. Considering the dangers of wild animals and the competitiveness of the gold rush, pioneers endured a darker version of the west, one overshadowed by Disneyland’s profitable presentation of history.

Walt Disney again perpetuated western myths in designing the Mark Twain riverboat, which he “wanted . . . to be authentic” even though “like most of Disneyland, the boat is under-scale to give a fantasy-like appearance.”[17] In intentionally under-scaling the boat, Disney promoted his plastic vision of the west over the practical needs of the time. While the steamboat operated for pragmatic transportation during American expansion, in Frontierland it merely circles around a man-made river to bring passengers into a world as imaginary as the ones fiction writer Mark Twain himself created, adding to the park’s embellished narrative. Alongside these attractions, Frontierland’s fabricated story came to life through live performances; for example, adorned vigilantes and cowboys would perform shoot-outs, since, as a Disney documentary notes, “every frontier town has its bad man and its brave sheriff to enforce the law.”[18] The characterizations “bad man” and “brave sheriff” stereotyped settler societies, simplifying the past so it may fit into the Happiest Place on Earth’s story, a fairytale catered to families paying for entertainment. The incorporation of glamorized architecture and entertainers across the park thus materialized western legends, for even the television stars of America’s beloved “Davy Crockett” made appearances.

Frontierland extravaganzas proved effective in earning profit, given that Americans spent over $300 million on Crockett merchandise by the end of the year that the actors of the show “Davy Crockett” attended Frontierland’s opening day in costume.[19] The many performers that popularized Walt’s wild west formed Frontierland into more of a theater stage than a historical replica. Furthermore, incorporating actual people into the illusion made it all the more real for audiences, common Americans looking to the country’s past for inspiration. While Disney stated his intention for Frontierland to serve as an honest history lesson, the park’s physical placement beside Fantasyland exposes its metaphorical manipulation of the nation’s culture. In romanticizing the life of a cowboy, the park also suppressed the stories of minorities who suffered during a period of such rapid settlement.

Fig. 1. Map of Frontierland, a park designed by Disney himself and built on the western side of Disneyland. Francaviglia, “Walt Disney’s Frontierland as an Allegorical Map of the American West,” 164.

As it glorified Anglo American tropes from its opening day, Frontierland segregated, misrepresented, and even villainized other cultures to present a palatable version of western history that the park’s customers would accept. When colonizers pushed to the west during expansion, the indigenous people of the land faced brutal treatment. One could also note that native tribes operated in non-capitalist systems, and thus struggled to survive as industry engulfed American people, land, and culture.[20] While Walt acknowledged the existence of natives in designing his attractions, he detached them from the rest of his frontier and forced them into outskirt “authentic Indian Villages . . . where Indians of thirteen tribes perform[ed] ancient ritual dances."[21] The script narrated to guests, who observed tribal performers from the park’s perimeter as if at a zoo, referred to the native practices as “ancient” to imply that indigenous culture held little significance at the time of expansion. Moreover, the fact that visitors could meet a “full-blooded Indian Chief” and ride one of the “Indian War Canoes” that circled around Tom Sawyer’s Island exposes Disney’s conflicting message: Native Americans could serve as the white hero’s “chief ally” or his “most treacherous and ubiquitous threat.”[22] The war canoe tour even warned that “some Indians are hostile, and across the river is proof . . . a settler’s cabin afire. The pioneer lies in his yard . . . victim of an Indian arrow,” presenting the nation’s first people as savages.[23] The tour taught children and adults to associate native people with violence because if Disneyland’s initial prime audience, a 1950s American family with disposable income, had to confront the darkness of colonization, the amusement park would fail in monetizing amusement and betray its business model: making money off of dreams. So, whether a guest regarded indigenous people with curiosity, fear, or any feeling in between, Frontierland muffled tribe histories to prioritize the comfort of consumers.

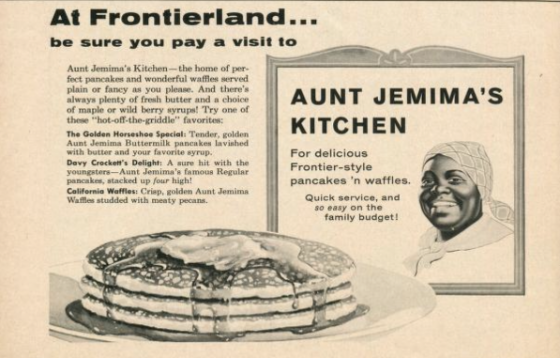

Frontierland skewed African American stories as well, as the South’s unjust past failed to fit into Walt Disney’s nostalgic dreamland. Upon opening day, Frontierland featured a sponsored Aunt Jemima pancake house on New Orleans Street, where a Black actress performed as the franchise’s famous mascot.[24] The commercialized venue perpetuated racial stereotypes, namely the smiling, submissive servant of plantation times. Thematizing the restaurant around a popular character, portrayed by a Black woman on site, solidified this degrading role as a true one in the minds of consumers, despite the fictitious trope it represented. Plastered with Aunt Jemima’s beaming face, one advertisement stresses the “quick service” for meals “so easy on the family budget!” evoking a dynamic of master and servant. Marketing pancakes cooked “hot-off-the-griddle” by a Black cook, Frontierland avoided addressing slavery, secession, and the Civil War, key factors in New Orleans history.[25] Frontierland took advantage of history rather than honoring it, as the cultural parts of the park were rooted in promoting profit instead of reality. The company later replaced the ethnic-based attractions; yet, as scholar Victoria Pettersen Lantz has expressed, this gesture “create[d] indexical absence of nativeness” like a corporate cover-up.[26] While Disney could have reconfigured Frontierland to project unheard voices of the past, silently removing minorities from the story preserved the image of Walt Disney’s seemingly wonderful West. This problematic presentation of pioneer times proves to be just as difficult in the current age, given that the Walt Disney Company’s version of the frontier still aims to appeal to Americans while also endearing itself to international markets, with many of these new audiences distanced from the American dream.

Fig. 2. Advertisement for Aunt Jemima’s kitchen, published in a Disney sponsored magazine. Disney, Walt, editor. VacationLand, 1960.

While Disney has retired many of its past attractions, Frontierland still monetizes Western myths as it infuses contemporary culture into its rustic realm to mislead an even wider audience, since the theme park itself expands across the globe like the pioneers of the past. When Walt Disney addressed the future of his frontier, he spoke with irony as he planned to create “new exhibits that will show today’s youth the America of our great-grandparents’ day and before.”[27] Building brand new sites to share traditions of the past defies reason because, although Walt could add shiny attractions to his realm, one cannot update history to fit personal goals. So, Disney’s wish to upgrade Frontierland exposes his disregard for the nation’s original stories. Scholar Richard Francaviglia explained Frontierland’s conflicting influences of past and present, noting that Disney’s “romanticizing of the ‘Old West’ helped lay the groundwork for the ‘New West’ of amenity tourism and chic residence,” indicating that this rewritten version of pioneership is rooted in profitability.[28] Though Walt Disney himself has passed away, the “New West” he set out to design lives on as a commercialization of the quintessential American Dream. In fact, Disneyland’s official website currently encourages Frontierland visitors to “Blaze fun new trails like a real pioneer — explore attractions, entertainment, shopping, dining, and more!” as if authentic frontiersmen lived like road tripping vacationers.[29] The emphasis on tourism in describing the park accentuates the industrial motivation behind Disney’s myth. The company’s original audience—1950s American families—has evolved over the years, but the land’s mission to make money remains, so Frontierland has entered international markets as if channeling a pioneer’s instincts.

A park defined by its patriotism holds tremendous influence when placed in a foreign country, since many visitors stand outside of American culture and may interpret the theme as an authentic representation. An attendee at the opening of Disneyland Paris confirmed this effect when describing Frontierland as “the kind of place where John Wayne-loving Europeans can get a dose of what they must think is America,” highlighting the public’s misperception of not just the West, but —more completely— “the land of the free.”[30] Disney popularized western whimsies, but also adjusted these myths to entice those detached from the nation’s promises. For instance, Tokyo Disney notably renamed the park as “Westernland” because, as one spectator admitted, Japanese visitors “could identify with the old West, but not with the idea of a frontier,” suggesting that the pioneer’s pursuit of dreams may be exclusively American.[31] The reactions from international audiences showcase Frontierland’s effectiveness in maintaining a mythological American persona, one bold enough to identify with the opportunities of a frontier. Ultimately, the Frontierland of today is an ever-changing one, always adjusting to meet the demands of capitalism and its elevation of the American dream.

Reconfiguring the nation’s history to curate a fantasy, Disney’s Frontierland financially flourishes in romanticizing the reality of the Old West because Americans aspire to pave paths for their hopes the way that pioneers followed the trails of capitalist goals. With frontier myths, free markets, and theme parks intertwined into Walt Disney’s early life, the dreamer acted as a frontiersman himself when he invested all he could into his California fantasy world. While he found unlikely success in this feat, he manipulated the public in doing so, inventing for his Wild West a wonderland filled with exaggerated sights. This land oppressed critical narratives of the past and thus upheld racist tendencies in the Happiest Place on Earth, exacerbating the myth of white heroes shaping the west. Finally, the Walt Disney Company continues to promote western falsehoods in the modern age, especially as it reaches international audiences and presents Americans as dreamers above all else. On the surface, Frontierland seems like a simple source of fun the whole family can enjoy. Yet a closer look exposes the park’s plasticity and the potential danger in selling citizens a glamorized “truth.” Capitalism guided the path of westward expansion, and it continues to forge what society has accepted as the American way through powers like the Walt Disney Company. The fact that so many people prefer to pay for Frontierland’s myths rather than acknowledge an imperfect past illuminates an inherent need, which both defines and unites the American identity: the drive to dream. Whether wishing upon a star, investing in a new company, or simply spending a day with family, those lured to Frontierland embrace a fake portrayal of yesterday because they crave a better tomorrow. As long as Frontierland remains wedged between a castle and a spaceship, its visitors will leave with a newfound loyalty to the American Dream, no matter how much it will cost their wallets or their souls.

Notes

[1]. Disney, Walt. “Walt Disney's Opening Day Speech - Disneyland 1955.” Youtube, 16 July 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6uuC3kS9kxk.

[2]. Francaviglia, Richard. “Walt Disney's Frontierland as an Allegorical Map of the American West.” The Western Historical Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 2, 1999, pp. 155–182. https://doi.org/10.2307/970490; Turner, Frederick Jackson. Rereading Frederick Jackson Turner: “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” and Other Essays. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998.

[3]. Wrobel, David M. “Capitalism and the American West: Macrocosm and Microcosm.” Reviews in American History, vol. 24, no. 2, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, pp. 258–64, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30030654.

[4]. Klein, Christopher. “Why Did the Pilgrims Come to America?” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 13 Nov. 2020, https://www.history.com/news/why-pilgrims-came-to-america-mayflower.

[5]. Wallerstein, Immanuel. “The West, Capitalism, and the Modern World-System.” Review (Fernand Braudel Center), vol. 15, no. 4, Research Foundation of SUNY, 1992, pp. 561–619, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40241239, 565.

[6]. Qtd. in Wallerstein, “The West,” 561.

[7]. Mittermeier, Sabrina. A Cultural History of the Disneyland Theme Parks: Middle Class Kingdoms. Intellect, 2021, 6.

[8]. Mittermeier, Cultural History, 8.

[9]. Francaviglia, “Frontierland,” 159.; Parisot, James. American Expansion: The Transition to Capitalism on the Frontier of Colonization, State University of New York at Binghamton, Ann Arbor, 2016. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/american-expansion-transition-capitalism-on/docview/1858568642/se-2?accountid=9703; Udall, Stewart L. The Forgotten Founders: Rethinking the History of the Old West. Washington, D.C: Island Press, 2002.

[10]. Parisot, James. How America Became Capitalist: Imperial Expansion and the Conquest of the West. Pluto Press, 2019; Robbins, William G. “In Pursuit of Historical Explanation: Capitalism as a Conceptual Tool for Knowing the American West.” The Western Historical Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 3, Utah State University, 1999, pp. 277–93, https://doi.org/10.2307/971374.

[11]. Disney, Walt. “Frontierland,” True West, 5 (June 1958).

[12]. Disney, “Frontierland.”

[13]. Mittermeier. Cultural History, 2.

[14]. Mittermeier, Cultural History, 3; Disney, Walt. “Walt Disney's Opening Day Speech.”

[15]. Smith, Dave. The Quotable Walt Disney. 1st ed., Disney Editions, 2002.

[16]. Disney, Walt, editor. VacationLand, 1960, pp. 1–20, https://archive.org/details/Vacationland1960Summer.

[17]. Disney, "Frontierland.”

[18]. Luske, Hamilton S., director. Disneyland, U.S.A. People and Places: Disneyland, U.S.A., Walt Disney Productions, 22 Aug. 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BJpcH_vA11s.

[19]. Mittermeier, Cultural History, 34.

[20]. Parisot, “American Expansion,” 89.

[21]. Francaviglia, “Frontierland,” 175.

[22]. Ibid.

[23]. Ibid.

[24]. Steiner, Michael. “Frontierland as Tomorrowland: Walt Disney and the Architectural Packaging of the Mythic West.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, vol. 48, no. 1, Montana Historical Society, 1998, pp. 2–17, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4520031, 12.

[25]. Disney, VacationLand.

[26]. Mittermeier, Cultural History, 32.

[27]. Disney, “Frontierland.”

[28]. Francaviglia, “Frontierland,” 167.

[29]. Disneyland. https://disneyland.disney.go.com/.

[30]. Los Angeles Times, May 3, 1992, sec. L, p. 2.

[31]. Los Angeles Times, July 17, 1983, sec. 7, p. 3

Bibliography

“Atlas of Westward Expansion.” The SHAFR Guide Online, https://doi.org/10.1163/2468-1733_shafr_sim060070038.

Carney, Elizabeth. “Suburbanizing Nature and Naturalizing Suburbanites: Outdoor-Living Culture and Landscapes of Growth.” Western Historical Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 4, Oxford University Press, 2007, pp. 477–500, https://doi.org/10.2307/25443607

Disney, Walt. “Frontierland,” True West, 5 (June 1958)

Disney, Walt, editor. VacationLand, 1960, pp. 1–20, https://archive.org/details/Vacationland1960Summer..

Disney, Walt. “Walt Disney’s Opening Day Speech - Disneyland 1955.” Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6uuC3kS9kxk.

Disney, Walt. Walt Disney's Wonderful World of Color. Youtube, Walt Disney Records, 1956, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uz__bJTlOjk.

Disneyland. Visit Disney.com. https://disneyland.disney.go.com/.

Dougherty, Michelle. America’s Kingdom: Disneyland as a “Performance of American Family Identity in the 1950s. The Florida State University, Ann Arbor, 2012. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/americas-kingdom-disneyland-as-performance/docview/1095742993/se-2?accountid=9703.

Francaviglia, Richard. “History after Disney: The Significance of ‘Imagineered’ Historical Places.” The Public Historian, vol. 17, no. 4, [National Council on Public History, University of California Press], 1995, pp. 69–74, https://doi.org/10.2307/3378386.

Francaviglia, Richard. “Walt Disney's Frontierland as an Allegorical Map of the American West.” The Western Historical Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 2, 1999, pp. 155–182., https://doi.org/10.2307/970490.

Hulse, Jerry. “Dream Realized—Disneyland Reopens.” Los Angeles Times, 16 July 1955.

Hyde, Anne F. “Cultural Filters: The Significance of Perception in the History of the American West.” The Western Historical Quarterly, vol. 24, no. 3, Aug. 1993, pp. 351–374., https://doi.org/10.2307/970755.

Klein, Christopher. “Why Did the Pilgrims Come to America?” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 13 Nov. 2020, https://www.history.com/news/why-pilgrims-came-to-america-mayflower.

Leetch, Tom, director. The Magic of Walt Disney World. Walt Disney Records, 20 Dec. 1972, Accessed 1 Dec. 2021.

Los Angeles Times, July 17, 1983, sec. 7, p. 3

Los Angeles Times, May 3, 1992, sec. L, p. 2.

Luske, Hamilton S., director. Disneyland, U.S.A. People and Places: Disneyland, U.S.A. , Walt Disney Productions, 22 Aug. 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BJpcH_vA11s.

Marling, Karal Ann. “Disneyland, 1955: Just Take the Santa Ana Freeway to the American Dream.” American Art, vol. 5, no. 1/2, [University of Chicago Press, Smithsonian American Art Museum], 1991, pp. 169–207, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3109036.

Mittermeier, Sabrina. A Cultural History of the Disneyland Theme Parks: Middle Class Kingdoms. Intellect, 2021.

Mittermeier, Sabrina. A Cultural History of the Disneyland Theme Parks: Middle Class Kingdoms. Intellect, 2021.

Parisot, James. American Expansion: The Transition to Capitalism on the Frontier of Colonization. State University of New York at Binghamton, Ann Arbor, 2016. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/american-expansion-transition-capitalism-on/docview/1858568642/se-2?accountid=9703.

Parisot, James. How America Became Capitalist: Imperial Expansion and the Conquest of the West. Pluto Press, 2019.

Robbins, William G. “In Pursuit of Historical Explanation: Capitalism as a Conceptual Tool for Knowing the American West.” The Western Historical Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 3, Utah State University, 1999, pp. 277–93, https://doi.org/10.2307/971374.

Smith, Dave. The Quotable Walt Disney. 1st ed., Disney Editions, 2002.

Steiner, Michael. “Frontierland as Tomorrowland: Walt Disney and the Architectural Packaging of the Mythic West.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, vol. 48, no. 1, Montana Historical Society, 1998, pp. 2–17, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4520031.

Tobin, Joseph Jay, and Mary Yoko Brannen. “Bwana Mickey: Constructing Cultural Consumption at Tokyo Disneyland.” Re-Made in Japan: Everyday Life and Consumer Taste in a Changing Society, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1994.

Turner, Frederick Jackson. Rereading Frederick Jackson Turner: “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” and Other Essays. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 1998.

Udall, Stewart L. The Forgotten Founders: Rethinking the History of the Old West. Washington, D.C: Island Press, 2002.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. “The West, Capitalism, and the Modern World-System.” Review (Fernand Braudel Center), vol. 15, no. 4, Research Foundation of SUNY, 1992, pp. 561–619, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40241239.

Wrobel, David M. “Capitalism and the American West: Macrocosm and Microcosm.” Reviews in American History, vol. 24, no. 2, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, pp. 258–64, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30030654.