Out West: The Queer Sexuality of the American Cowboy and His Cultural Significance

by Hana Klempnauer Miller

Research Paper | UWS 53b Mythology of the American West | Eric Hollander | Fall 2021

About this paper | This paper as PDF | MLA format

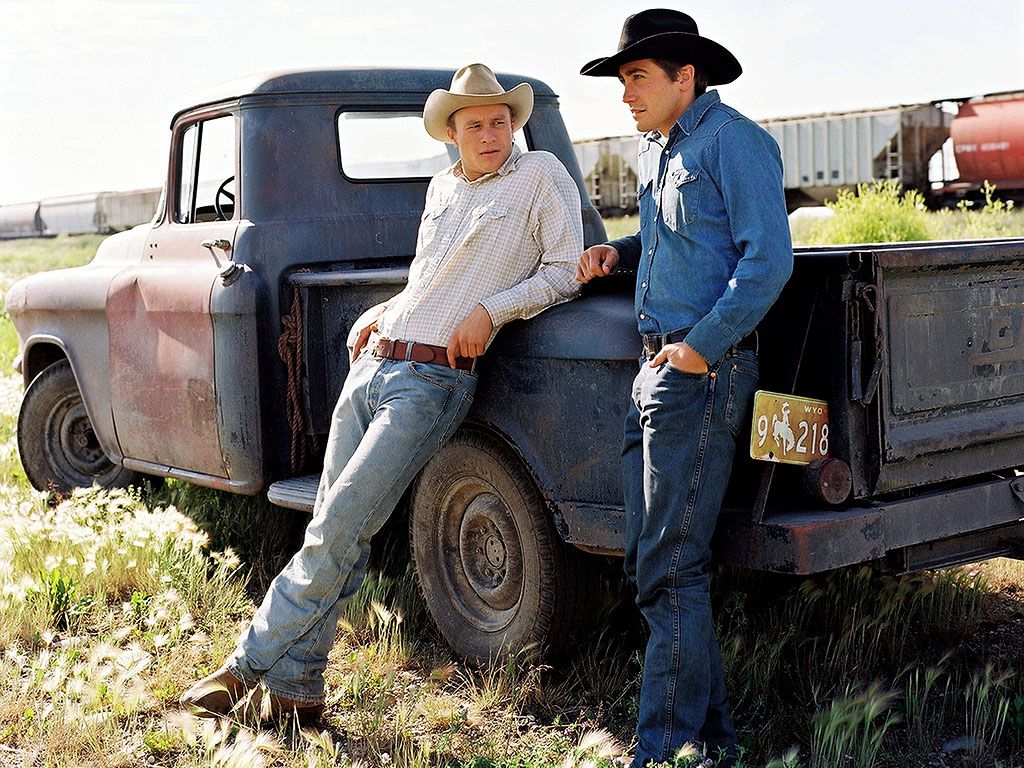

Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal in a scene from Brokeback Mountain.

Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal in a scene from Brokeback Mountain.

Ask anyone who’s seen Brokeback Mountain (2005) to characterize the film in three words, and you’re almost certain to hear some variation of “gay cowboy love-story.” While many have lauded the film, directed by Ang Lee, for its nuanced portrayal of two men’s complicated love for each other, the film was subject to scathing criticism at the time of its release. Detractors, largely spearheaded by right-wing and religious groups, quickly and fervently deemed the film’s depiction of a homosexual couple immoral, evidence of an attempt to feminize men, and even anti-American. In many cases, critics honed in on the two leads ’ occupations as cowboys, challenging the existence of a “gay cowboy” in American history. One critic wrote that the film was a “mockery of the Western genre embodied in every movie cowboy from John Wayne to Gene Autry to Clint Eastwood. I can’t think of a more effective way to alienate most movie-going Americans than to show two cowboys lusting after each other and even smooching.” Other critics accused filmmakers of pushing an “agenda” onto Americans, with one writing that “Hollywood screenwriters and producers think that it’s their duty to teach America that homosexual conduct and cross-dressing are normal behaviors that should be affirmed in American culture. […] We have never accepted the belief that same-sex relationships or transvestism are simply variations of human sexuality” ( critics cited in Patterson l-lii). These beliefs, though objectively baffling, beg interesting questions: Was homosexuality ever accepted in America’s past? How was sexuality actually viewed in the Old West? And why does challenging this mythologized image of the cowboy spur such a vitriolic response?

In this essay, I will examine these questions first by defining the mythologized image of the American Cowboy. I will then use contextual evidence to explain the significance of the cowboy myth in contemporary American society. Next, I will trace the origins of the cowboy myth down to its literary roots. Specifically, I will discuss James Fenimore Cooper’s saga , The Leatherstocking Tales as the literary origin of the mythologized cowboy. Supported by secondary sources, I will argue that this myth is rooted in homoerotic relationships, a reflection of historical fact. In light of this contention, I will explore the realities of homosexuality and homosociality amongst cowboys in the Old West, arguing that they were accepted and commonplace. Finally, I will return to the negative reception to Brokeback Mountain, where I will argue that the reason why the image of two cowboys in a romantic relationship was so hard for some Americans to understand was because it challenges conceptions of American masculinity tied to the cowboy myth that position themselves in direct opposition to queer identity. Ultimately, I will conclude that Americans need a better myth, and that Brokeback Mountain is a promising alternative.

In order to understand the nuanced sexuality of the historical cowboy , it is important to first dissect the mythologized version. Myths are particularly effective ways for learning and understanding history, and in American culture, few myths are as recognizable as the cowboy. As historian Richard Slotkin puts it, myth is “the primary language of historical memory: a body of traditional stories that have over time been used to summarize the course of our collective history and to assign ideological meanings to that history” (Slotkin as cited in Capozzi). In this way, myths serve to define a culture, and more importantly, how proponents of that culture want to be defined. But who is this mythologized cowboy, the figure that critics like those mentioned earlier are so eager to preserve? For many, the likes of John Wayne, Clint Eastwood, the Marlboro Man, or the Lone Ranger immediately spring to mind. Icons in their own right, they represent the mythologized image of the American cowboy as a symbol of ideal masculinity who embodies the most precious values of the country. With the performances of these men, Hollywood has functioned as the creator and keeper of the modern cowboy myth.

Westerns suggest that cowboys are gun-toting men on horseback, riding tall in the saddle, unencumbered by civilization, and, in Teddy Roosevelt’s words, embodying the “hardy and self-reliant” type who possessed the “manly qualities that are invaluable to a nation” (Roosevelt). As queer historian Chris Packard writes in his book Queer Cowboys, the mythologized cowboy, as defined by Hollywood, “teaches boys and men to emulate a cluster of behavior, values, and actions and frames of reference that connote idealized manhood. Ruggedness, ingenuity, and fearlessness are all qualities the cowboy embodies, while feminine qualities such as domesticity, weakness, and purity are anathema to his unwritten masculine code” (2). In this way, the Hollywood Cowboy, a term I will use interchangeably with mythologized American Cowboy, has come to be inherently associated with conceptions of masculinity for American men.

Hollywood, however, is not where the myth of the American Cowboy was first developed. The origins of the mythical American Cowboy can be attributed to author James Fenimore Cooper. Cooper pioneered the use of distinctively American scenes and images as central motifs in his fiction, contrasting the European fare that had defined popular American literature until that point. His influence on American literary and popular culture is difficult to overstate. First with The Pioneers in 1823, and later with The Leatherstocking Tales, Cooper established the frontiersman as a folk hero and the literary forefather of the Hollywood Cowboy. Cooper was, according to D. H. Lawrence, writing myth, an original American myth. He created the first frontiersman in order to say something about white masculinity in nineteenth-century America. Enmeshed in these stories, parallel to the sagas of exploration, adventure, and American excellence, are deep explorations of male-male relationships.

Specifically looking to Cooper’s masterpiece, The Leatherstocking Tales, the relationship between protagonist Natty Bumppo and his “fri’nd” Chingachgook is deeply romantic and intimate. As D. H. Lawrence describes it, the two characters have a relationship “deeper than the deeps of sex .” While Cooper does not detail explicit sex between the two, their relationship is unmistakably homosocial. Over the course of the five novels that make up the overall saga, the two men consistently reject women in favor of maintaining a relationship with each other and come to share their wealth, their beds, and their bodies, even adopt ing children together. Theirs is, in no uncertain terms, a marriage, but one that is also radically different from heterosexual relationships of the time. Their bond does not presuppose gender-based dichotomies.

In this way, their relationship can be seen as one inherently threatening to the modern conceptions of heterosexuality and masculinity that are defined by strict gender roles. As opposed to being defined in opposition to a heterosexual relationship, their love does not, as Packard contends, “function by mirroring the Other but by exchanging difference and inculcating the Other into the Self” (33). Their bonds are in part erotic, but without the constraints of sexual categories that limit thinking about sexuality today. Cooper described love stories between men that are erotic, but they do not deploy the pejorative view of “deviant sexual categories” that would develop by the turn of the twentieth century. In this way, Cooper has embedded an acknowledgement of same-sex love in the very heart of American myth, directly contrasting claims that homosexuality is an unnatural and/or modern invention. Furthermore, the homosociality described in Cooper’s work is not purely imaginative, but actually reflective of historical records indicating the presence of homoerotic relationships among cowboys in the frontier west, in keeping with Cooper’s assertion that these stories were inspired by tales he had been told by actual cowboys.

While the image of the cowboy as a “lone ranger” riding in solitude is popular in the media, the historic cowboy actually relied on a partner or partners to survive. These men depended on one other to survive the hostile environment of the frontier. “Homoerotic friendships preserve privilege and ensure survival in a hostile wilderness” (Packard 15). Cowboys often served as their partner ’s only human connection during the long periods on the range and relied on one another for their very survival. These partners did everything together, from eating to sleeping, and developed strong relationships. In turn, many sought out sexual intimacy from their few companions on the range (Garceau 154). However, modern conceptions of sexual identity were still in their infancy at this time , and engaging in male-male sex did not necessarily mean that a cowboy had to rethink his sexual identity. Homosexuality was an act , not an orientation. Nevertheless, it’s highly likely that among cowboys, as among other largely male communities isolated from women, such as loggers, miners, and sailors, male-male sexual relationships were relatively common (Patterson 108).

This is also consistent with findings like those in Alfred Kinsey’s notorious 1948 study , Sexual Behavior in the Human Male , which reported the highest frequencies of homosexual intimacy to be among men in rural farming communities; probably, Kinsey concluded, much like their pioneer forebearers in the frontier west. Indeed, Kinsey’s contention reflects primary source material indicating homosexual relationships among frontier cowboys. One such source, a limerick that alludes to homosexual intimacy between cowboys, was found by historian Clifford Westermeier and published in his 1976 essay “The Cowboy and Sex.” The last stanza is of particular interest. It reads:

Young cowboys had a great fear,

That old studs once filled with beer,

Completely addle’

They’d throw on a saddle,

And ride them on the rear.

This suggests not only the presence of homosexual intimacy in the frontier west, but also a greater culture of sexual ambiguity. Historically, the cowboy was able to engage in homosexual sex while maintaining his masculinity and status. This dichotomy has seemingly disappeared in the Hollywood Cowboy.

Indeed, in the construction of the cowboy in narratives of Western adventure in pop culture, the Hollywood Cowboy’s masculinity is supposedly antithetical to same-sex desire. Thus, critics have attempted to reductively assess the historical evidence, saying that cowboy sexual relationships were purely physical, almost clinical ways for cowboys to relieve sexual frustration in an environment void of women. This narrative, however, omits the presence of men who loved men. Written by Badger Clark, who is often regarded as the most prolific cowboy poet, “The Lost Pardner” laments the loss of Clark’s partner “Al.” It emphasizes, in addition to a physical intimacy between the two men, a deep romantic connection. The second half of the poem reads:

We loved each other in the way men do

And never spoke about it, Al and me,

But we both knowed, and knowin' it so true

Was more than any woman’s kiss could be.

What is there out beyond the last divide?

Seems like that country must be cold and dim.

He’d miss this sunny range he used to ride,

And he’d miss me, the same as I do him.

It’s no use thinkin'—all I’d think or say

Could never make it clear.

Out that dim trail that only leads one way

He’s gone—and left me here!

The range is empty and the trails are blind,

And I don’t seem but half myself today.

I wait to hear him ridin' up behind

And feel his knee rub mine the good old way.

The inferences made in the poem position the two partners as more than mere friends. For instance, their knees rubbing together in “the good old way,” coupled with the rhyming of “ridin’” and “behind” with “mine” suggest that perhaps it was not only their knees that were rubbing. Additionally, Clark’s assertion that they loved each other “in the way men do,” suggests an intimate connection. The poem describes a connection between the two that is more than just physical. Referring to their love, Clark laments they “ knowed” their love was “more than any woman’s kiss could be.” This implies an understanding of same-sex love deeper than a merely physical attraction. The italicization of knowed in the original implies that this love could go without needing to be said. Clark understood that this relationship was truer than one he could have with a woman.

A same-sex relationship like that described in “The Lost Pardner” was not anomalous among historic cowboys. In fact, these kinds of relationships would have been a great privilege on the range, because they allowed the cowboy to retain his independence while fulfilling the basic human desire for affection and companionship. Affection for women often spelled the end of a cowboy’s career, as it produced children and created familial responsibilities that would ultimately hamper the cowboy’s ability to ride the range freely. Men were commonly affectionate with one another, engaging in a level of closeness that their Eastern counterparts may not have accepted. Homosociality was core to community in cowboy culture, allowing men to connect with others without societal retribution (Packard 3,7).

But how then did such a developed community become erased from the history books? The answer lies in the canonization of the myth. It is largely agreed that the end of frontier culture in the West happened around 1890, when the superintendent of the US Census declared that population was increasing at such a rate that they could no longer draw a frontier line between East and West (Turner). This was accompanied by an influx of Easterners who brought with them what historians termed the “modern” sexual and gender system (Boag 4). Thus, at the same time as Americans began to memorialize the frontier, they were cementing the sexual and gender binary. It held that gender behavior (how someone acts, feels, and thinks) corresponds to physiology. Among these behaviors is sexual intercourse. Under this binary system, there should only be opposite-gender attraction. The idea depended on the explanation that this is how nature determined it. Consequently, those who did not subscribe to such binaries were seen as unnatural. The term “sexual invert” was developed to refer to these people and was used interchangeably with “homosexual” (Boag 5). Concurrently, the concept of “sexual inversion/homosexuality” evolved in direct contrast to “heterosexuality.” From the start, homosexuality was defined as innately “unnatural,” and therefore sexually deviant. Moreover, in the use of “sexual invert,” homosexuality became inherently linked to effeminacy. Given the Otherness attributed to women, one that was created to enhance the primacy of male identity, to infer a man held effeminate qualities was directly contradictory to his masculinity.

Thus, in the process of elevating the cowboy’s image to what was to become the Hollywood Cowboy, mythmakers faced a problem. The West was the supposed birthplace for this new nation, and the character of those who tamed it would presumably be those of the ideal citizen, but the cowboy population consisted of openly queer people. If the mythmakers were to admit that the West was won by the very people it claimed as deviants, it would threaten the justifications for Westward Expansion itself. As Peter Boag explains, “to identify a homoerotic core in its myth about the supremacy of white American masculinity is to imply that American audiences want their frontiersman to practice nonnormative desires as part of their roles in nation-building” (12). In other words, if there is something national about the cowboy and if there is something homoerotic about the partnerships he forms in the wilderness, then there is something homoerotic about American national identity. This would be something seemingly contradictory to the reinforcement of homosexuality as Other and anathema to the American/masculine ideals the cowboy was supposed to represent. Accordingly, mythmakers sought to erase any and all lasting ties between men, and the image of the cowboy as a lone ranger was born. This begins to explain why critics were so threatened by Brokeback Mountain, as the depiction challenged these longstanding binaries. This is to say that the portrayal of two masculine icons engaging in behavior that was been deemed antithetical to American masculinity fractures the groundwork of the modern myth by showing the reality of what it had deemed impossible.

The very notion that two men could be vulnerable and intimate with each other and maintain their masculinity negates the core conceptions of American masculinity that the Hollywood Cowboy ingrained in society. Thus, for those whose masculinity is tied to that image of the Hollywood Cowboy, Brokeback Mountain exposes the paradoxical nature of their identity by challenging the metric through which they qualify their own identity. In forcing the audience to recognize a deeper connection between the two protagonists, one that may reflect feelings held by many other American men, the audience is compelled to acknowledge the artificial boundary between homosocial and homoerotic that is imposed by homophobia and reinforced by the Hollywood Cowboy. By doing so, the audience is provided with a window into a new, healthier approach to the myth of the American Cowboy and American masculinity. As Eric Patterson concurs, “By locating love between men within the iconographic system of landscape, clothing, and activities that are fundamental to the Western, Brokeback Mountain obliges readers and audiences to begin to recognize how the American national fantasy of Western adventure and particularly the idealized cowboy hero have distorted history and endorsed a homophobic construction of masculinity” (117). In challenging the myth of the Hollywood Cowboy, Brokeback has not only presented a more historically honest narrative but highlighted the revisionist history perpetuated by the Hollywood Cowboy. If nothing else, the incongruity of the film with the Hollywood Cowboy demonstrates the exclusionary nature of America’s mythos and the need for a more inclusive fantasy.

In order to reinforce justification for westward expansion and preserve systems of white supremacy, the image of the American cowboy came to be, almost exclusively, a straight, white man. Consequently, the contribution of actual historic cowboys—who included queer people and people of color—to the “taming” of the wild west, was erased. In omitting everyone but Anglo Americans from the cowboy myth, we Other a large swath of Americans. It implies that only straight, white men can perform idealized masculinity. Moreover, this omission suggests that an individual who does not meet those qualifications cannot be a true American. In his “Cowboy Commandments,” film star Gene Autry emphasizes “A cowboy is a patriot” ; therefore it stands to reason that a non-myth-conforming cowboy is merely playing dress up, impersonating a true American, perhaps even mocking that which the Hollywood Cowboy holds dearest—his love of country.

Americans need a more inclusive myth that can better represent the vast diversity of Americans. Brokeback Mountain serves as one viable rubric for a new kind of myth. It preserves many of the core tenets that define the American Cowboy. The cowboy as a master of independence, self-reliance, control, and passion are all preserved in Brokeback ’s narrative. Moreover, in its filming, Brokeback Mountain , clearly recalls the sweeping, epic visual style of major Hollywood Westerns of the past, inviting the audience to recognize the commentary that it provides on American constructions of masculinity and sexuality that have been so fundamental to the national tradition of the Hollywood Western. Instead of the masculine morals taught by the Hollywood Cowboy, Brokeback teaches universal lessons about being true to oneself, the destructive costs of suppressing one’s identity, and the repercussions of living in a society that doesn’t tolerate diverse identities. To those who can only perceive love between men in terms of their own fears about themselves, these lessons remain meaningless, but to those Americans who look for something deeper and are not afraid to confront the truth of American frontier history, stories like these can change America. By better understanding our true history, Americans are given the opportunity to confront a cycle of oppression that the Hollywood Cowboy myth has been instrumental in perpetuating and ride off toward a brighter future.

Works Cited

Autry, Gene. “Gene Autry's Cowboy Code: The Cowboy Code.” GeneAutry.com, 29 Sept. 2017, https://www.geneautry.com/geneautry/geneautry_cowboycode-code.html.

Boag, Peter. Re-Dressing America’s Frontier Past, U of California P, 2012.

Capozzi, Nicco. “The Myth of the American Cowboy.” Medium, 16 Feb. 2018, https://medium.com/@StormFoxEsq/the-myth-of-the-american-cowboy-22260d0fecd8.

Clark, Badger C. “The Lost Pardner.” In Sun and Saddle Leather, 3rd ed. Richard Badger, 1919.

Cooper, James Fenimore. The Leatherstocking Tales. Library of America. Viking Press, 1985.

Garceau, Dee. “Nomads, Bunkies, Cross-Dressers, and Family Men: Cowboy Identity and the Gendering of Ranch Work.” Basso, Matthew, Laura McCall, and Dee Garceau, eds. Across the Great Divide: Cultures of Manhood in the American West. Routledge, 2001, 149-168.

Kinsey, Alfred C. Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. W. B. Saunders Co., 1948.

Lee, Ang. Brokeback Mountain. Focus Features, 2005.

Lawrence, D. H. Studies in Classic American Literature. Thomas Seltzer, 1928.

Packard, Chris. Queer Cowboys: And Other Erotic Male Friendships in Nineteenth-Century American Literature. Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Patterson, Eric. On Brokeback Mountain: Meditations about Masculinity, Fear, and Love in the Story and the Film. Lexington Books, 2008.

Roosevelt, Theodore. Ranch Life and the Hunting-Trail. [Century Co, 1888]. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <lccn.loc.gov/03031226>.

Slotkin, Richard. “Myth and the Production of History.” In Bercovitch, Sacvan and Myra Jehlen, eds. Ideology and Classic American Literature. Revised edition, Cambridge UP, 1987.

Turner, Frederick Jackson. “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” In The Frontier in American History, 1920.

Westermeier, Clifford J. “The Cowboy and Sex.” In Harris, Charles W. and Buck Rainey eds. The Cowboy: Six-Shooters, Songs, and Sex. U of Oklahoma P, 1976, 85-106.