Who am I? And Who Are You? The Role of Documents in Creating Identity in 'Transit'

by Jordan Sims

Lens Paper | UWS 54B Thinking About Borders Through Data | Greg Palmero | Fall 2021

About this paper | This paper as PDF | MLA format

A scene from Transit.

A scene from Transit.

In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, when Alice meets a giant rabbit and suddenly finds herself nine feet tall, she asks, “Who in the world am I? Ah, that’s the great puzzle.” But an equally important question might be: “Who in the world am I perceived to be?” Transit, Christian Petzhold’s 2018 film adaptation of Anna Seghers’ 1944 novel, poses a related epistemic question, namely, “How do I establish any of this to the satisfaction of others (or even to myself)?” In the film, documents—identity papers, transit visas, manuscripts, diplomas—define, characterize, identify, and in some cases misidentify the central characters. The protagonist, a young man named Georg, finds himself in Marseille, fleeing fascists while in possession of a manuscript and two letters belonging to a deceased writer. But who, really, is Georg? The viewer is never told. The same is true of many of the characters, major and minor, in the film. A few—the bartender, the consular officials, the hotel concierge—are identified principally by their association with a place. Of others we know almost nothing, aside from the personal stories they tell and, more importantly, the documents they have, aspire to have, or do not have. Viewed through the lens of Lisa Gitelman’s work on documents, the answer to the crucial questions in Transit—How do I know who I am? How do I guarantee it to others? —is that identity is inseparable from documentation.

While documents are spoken of and displayed throughout the movie, it is worth asking what makes one object but not another a “document”? According to Gitelman, that question has been debated for centuries. She argues in her book, Paper Knowledge, that documents are “epistemic objects; they are the recognizable sites and subjects of interpretation across the disciplines and beyond, evidential structures in the long human history of clues” (1). The most common paper documents are those that derive their value from what Gitelman calls their “knowing and showing” characteristic. These are objects that, as all acknowledge, provide evidence of a specific and agreed-upon sort. They include the more obvious documents, such as identity cards, passports, and transit visas, that are the subject of much of the tension in Transit. But Gitelman is also concerned with “no show” documents, those that she suggests are kept for their “potential to show,” meaning that they might have documentary value at some point in the future (2). These documents too play a role in defining identity in Transit.

The opening scenes in Transit involve a chilling invocation of the fascist actors in World War II, depicting the use of “know-show” documents to classify broad groups of individuals as either “desirable” or “undesirable.” Gitelman describes this use of documents as “integral to the ways people think as well as to the social order they inhabit. Knowing-showing, in short, can never be disentangled from power—or more properly, control” (5). For example, when Georg goes to Weidel’s hotel to deliver the two letters on behalf of his acquaintance, he proceeds under the false pretense of renting a room. When he arrives, the young woman at the desk says, “Show me your papers” (00:04:10).[1] The command is characteristic of a police state, where documents are used to verify whether a person belongs or not. As the scene at the hotel unfolds, the young woman goes on to explain that “all guests are registered. ... As you know, Mr. Langeron insists on registering all aliens. Order must be maintained” (00:04:33 – 00:06:16). The use of documents here suggests that they serve an administrative objective, namely efficiency. Order can be more easily maintained if people are classified. Georg does not show her any papers. And when Georg returns to the bar where he is to reconvene with his acquaintance, he finds the latter (along with several other men) being detained by armed officers. When one of the officers demands to see Georg’s papers, he pretends to look for them on his body before striking the officer and running away. That immediately confirms for the viewer the nature of Georg’s environment: characters are identified by whether they possess the “right” documents, and those who do not are subject to detention and by implication face grave consequences should they be arrested by the occupying force.

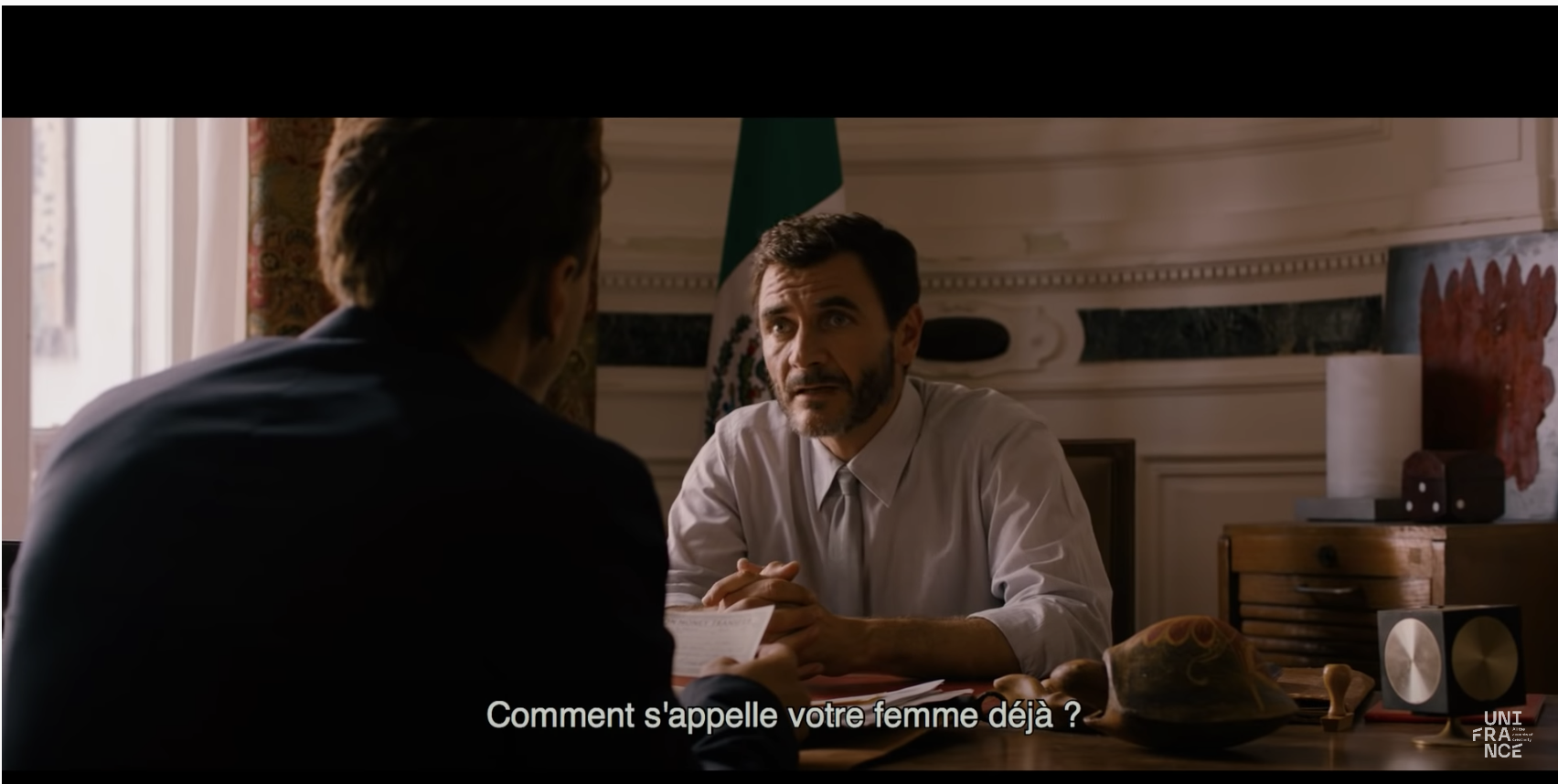

Conversely, Transit depicts the voluntary display of know-show documents as a means of establishing an individual’s power and legitimacy. This shows up, for example, in the way the American Consul is framed in the movie. Georg visits the embassy twice, first to obtain a transit visa for himself, and a second time to obtain one for Marie. In both instances, Georg and the Consul sit across from one another, separated by a desk that emphasizes both the distance and difference in circumstances between the two. Each scene opens with the camera focused on the Consul, seated behind the desk, his desk. Behind and to the left of the Consul is an American flag; to the right, on the wall, are framed official documents and a photograph; on the desk are documents that the Consul can provide or deny to the person seated in front of him and across the desk. The visualization of these objects—even the flag functions as a document—serve immediately to validate the Consul’s position of power. No music accompanies either scene. The distant sounds of traffic outside are all that can be heard. The quiet ambience of each scene emphasizes the seriousness of the conversations between the men. Few words are spoken. And none are necessary to establish that the Consul holds the power of life and death; Georg holds nothing.

Equally powerful in Transit to “know-show” documents are “no-show” documents. Documents of that sort function by little more than allusion to endow Georg with an identity—a pivotally important identity—that he does not actually possess. As the plot unfolds, they accomplish that feat without ever having to be “shown.” Until his arrival in Marseille, the viewer knows nothing about Georg other than he does not have the “right” set of identity papers. There is no back story that explains who he is or why he is in the predicament that he is in. It is only when he goes to the Mexican Embassy that an identity is attached to him. His intent is to deliver Weidel’s manuscript and inform the Mexican officials of his death. Georg is desperate with hunger, and his only hope is to “perhaps receive a finder’s fee and buy something to eat” (00:25:11). At that point, the documents he holds have taken on some potential value for him. He had not, however, thought so at first. After all, when he was told that one of the letters he was to deliver to Weidel was from his wife, he responded “So, who cares?” (00:02:08). But he did keep them, and now he is prepared to make use of them.

Georg does not mean to assume Weidel’s identity; the documents seemingly do that on their own. When he tells the clerk that he is there about the “Weidel matter” (00:29:39), the clerk misunderstands, and after speaking to the Consul he tells Georg that the Consul is expecting him. When Georg enters the Consul’s office, Georg’s identity—or at least his perceived identity—has changed by a mere reference to the name on the documents in his possession. He is no longer some hungry, unidentified, paperless stranger with documents to deliver. To the Consul, Georg is Weidel. That is clear when the Consul begins by noting that “Your wife was just here,” which leaves Georg looking puzzled (00:30:26), and then proceeds to provide Georg with documents: visas, ship passages, and a money order. These documents can provide Georg with the means to escape that he (and so many others) desperately seeks. But Georg is initially confused, informing the Consul that “Sorry, there has been a misunderstanding” (00:30:55). Thinking that Georg is confused about the need for transit visas, the Consul explains that they are necessary because the ships must stop in both Spain and the United States, as there “is no direct passage to Mexico” (00:30:55). Then, in a moment of doubt, he asks Georg his “wife’s” name. It is at this point that Georg understands and searches his recollection for the letter in his possession, signed “Marie,” that she had written to her husband. With his knowledge of that “no show” document—about which he had previously said “who cares?”—Georg is able to provide the Mexican Consul with the name of Weidel’s wife, and in so doing document his identity as Weidel.

Franz Rogowski and Alex Brendemühl in a scene from Transit

Franz Rogowski and Alex Brendemühl in a scene from Transit

The interaction with the Consul is not the only time that the absence of documentation is used to define characters in the movie. It is most notable in the treatment of Driss and Melissa, the child and wife of Heinz, the mortally wounded man with whom Georg travelled to Marseille. While the interactions between Georg and Driss provide opportunities to humanize Georg, it is not clear what Driss’s role in the movie is, other than through his illness to introduce Georg to the doctor. But that introduction could have been arranged in any number of ways, for example through the heart attack of the conductor. In that sense, Driss and Melissa are transactional characters. But what makes their presence in the movie striking is not just their lack of documentation, but their apparent disinterest in pursuing documentation. When Georg goes to their apartment in search of them before he leaves, he finds another family occupying their space. Georg inquires after them and is told “They’re gone. . . Far away” (01:20:05-07). There is no further explanation. And from that point forward, it is as though they never existed.

The role that documents play in how others perceive us is central to how the characters in Transit are defined. Having possession of the “correct” documents can establish that you “belong,” that you have “authority,” that you have the “right” to undertake an activity. Gitelman argues that documents are meant to “document” (1). What she does not say, but what is nevertheless evident, is that in an organized modern society existence is tenuous for those without documentation. That is a central theme in Transit. Without documentation, you cannot prove who you are or aren’t; without them, in Georg’s case, he could not have assumed the identity of someone else. Whether we comprehend it or not, documents have the power to define us.

[1] Those four words echo the first clearly spoken dialogue of an earlier movie about documentation and transit in time of war: Casablanca, which predated even Seghers’ 1944 novel. Whether intended or not, the invocation of Casablanca conjures for the viewer the dystopian world that Georg inhabits.

Works Cited

Gitelman, Lisa. Paper Knowledge: Toward a Media History of Documents. Duke UP, 2014.

Transit. Dir. Christian Petzold. Music Box Films, 2018. Kanopy. Web. 10 Oct. 2021.