Maggie O'Farrell's 'Hamnet'

July 12, 2021

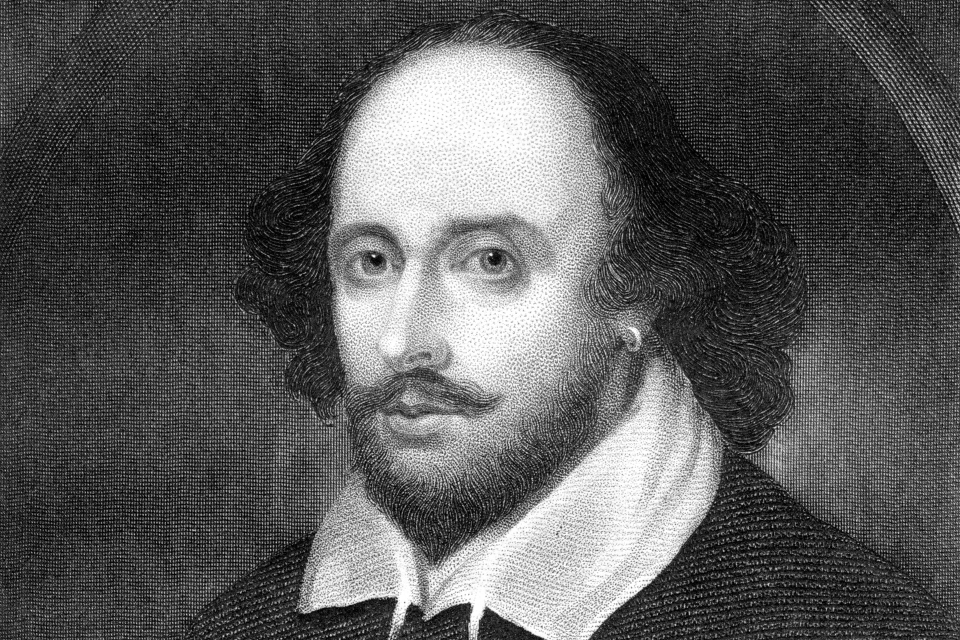

Photo Credit: Wynnter via Getty Images

by Marilyn Brooks

Béla Tarr, Sigmund Freud, Sylvia Plath, Alfred Hitchcock, James Joyce, Nicholas Cage — these are names that might not readily come to mind when discussing Maggie O’Farrell’s best-selling novel, "Hamnet." But it will come as no surprise to those familiar with Brandeis Professor Billy Flesch’s teaching style that all made at least one appearance during his recent faculty seminar devoted to O’Farrell’s work. Billy’s ability to “connect-the-dots” between so many people, places, and things deepened participants’ understanding of both "Hamnet" and William Shakespeare’s "Hamlet," which he taught earlier in the summer.

Like the prince in the play, the boy in the novel is missing his father, although in the latter’s case it is not death but the father’s ambition to go to London and write plays that takes him away from his son. Both the man and the boy are also grief-stricken, Hamlet in response to his father’s death and Hamnet to his twin’s illness.

O’Farrell takes readers to the years before Hamnet’s birth and those following his death. Her writing is so powerful and immediate that we are made to feel intimately involved with the playwright and his family, even though they lived more than five centuries ago.

Much of the novel is written in the style of “free indirect discourse,” a blend of first-and third-person narration, in which the author/narrator sometimes writes as if she/he is describing things from a character’s point of view, without its being followed by the usual “she said” or “she noted.” Since it is the viewpoint of Hamnet’s mother we see throughout most of the book, many of her thoughts and conversations are written in free indirect discourse, making her voice more powerful and direct, as if she is speaking to the reader without a narrator’s intervention. It should also be noted that O’Farrell calls her character Agnes, the name Shakespeare’s wife was given at birth, rather than the more familiar Anne.

Agnes’s psychic or spiritual power is so powerful that she can “read” the future. For example, she can tell when a woman is expecting a child without feeling the abdomen, as opposed to the lesser skill of her stepmother, who needs the physical touch. Jealousy is perhaps one of the reasons for Joan’s dislike of her stepdaughter and her desire to thwart Agnes in every way.

Agnes’s mother died giving birth to her third child, and shortly thereafter her father married Joan. They had six children together, in addition to Agnes and Bartholomew, the children from Mr. Hathaway’s first marriage. Joan made her stepdaughter’s life unpleasant in ways big and small: cutting her hair very short because she couldn’t be bothered combing it, throwing the dolls that Agnes’s mother had made into the fire, trying to prevent Agnes from marrying Shakespeare, and not disguising her envy at Agnes’s fine home, which was much nicer than her own.

Hamnet opens with the young boy returning home to find his twin sister, Judith, very ill. Although the house is usually filled with people — his mother, his grandparents, his older sister Susanna — no one is there other than Judith, who has fallen victim to bubonic plague. We follow Hamnet as he frantically runs through Stratford, looking everywhere for his family without success. When he returns home, frightened and bewildered by everyone’s absence, he falls asleep beside Judith, and we are left to understand that he, too, has been infected.

Most of all, Hamnet wants the comfort and assistance of his mother, a woman with almost supernatural healing abilities, like her mother before her. Townspeople regularly come to Agnes for her herbs, tinctures, and ability to diagnose and cure their ailments. It thus becomes even more poignant that there is nothing she can do to save her own son from death. This tragedy, which Agnes believes is her fault, will follow her for the rest of her life. “The compulsiveness of guilt through (one’s) imagination could alter reality,” noted Billy, and this is what almost happens to her.

One of the many wonderful features of Billy’s classes is his ability to identify things in a book or play that class members might have overlooked or misread. In Hamnet, for example, he pointed out the references to swelling — Agnes’s pregnancies, a gravid cat — and how these life-giving swellings are in opposition to the horrendous swellings symptomatic of the bubonic plague, with its grotesque and fatal buboes that appear on various parts of the body.

Another recurring concept in the novel is the idea of pairing, or doubling, of characters: Hamnet and Judith, Agnes and Shakespeare. We examined how the pairs are similar, different, or even an indispensable part of the other. The idea of being “one” with someone and then being separated from them is central to the story. As Billy put it, “who can telescope into whom” is a major theme in Hamnet. This is particularly true in the case of Hamnet and Judith who, aside from the fact that they are of different genders, are identical in looks. That Hamnet is the only one in the household to be infected by the plague after Judith is stricken is still another example of doubling.

Historians have made much of the fact that Shakespeare was eight years younger than his wife and that he left her and their children in Stratford for long periods of time to live and work in London. O’Farrell’s views of this and other puzzling incidents in Shakespeare’s marital life, such as leaving his “second-best bed” to his wife, offer readers a different understanding of their relationship, perhaps as a true love story.

“This book is a championing of Agnes,” Billy stated. Shakespeare’s wife was not a literary person, so O’Farrell’s retelling of the story of Shakespeare’s family is her way of putting Agnes’s life before us. Billy believes the author’s ability to see this world, a world that existed centuries before her own life began, “is an amazing thing to pull off.” O’Farrell’s view of Agnes and the life she led is central to the heart and soul of the novel.

In closing, Billy expressed his belief that “thoughtfulness is the highest praise I can give — this book is thoughtful.” Billy’s own thoughtful teaching and insights gave light to the many nuances and emotions O’Farrell gifted to her readers.