Henry James and the Art of Being Good

January 26, 2024

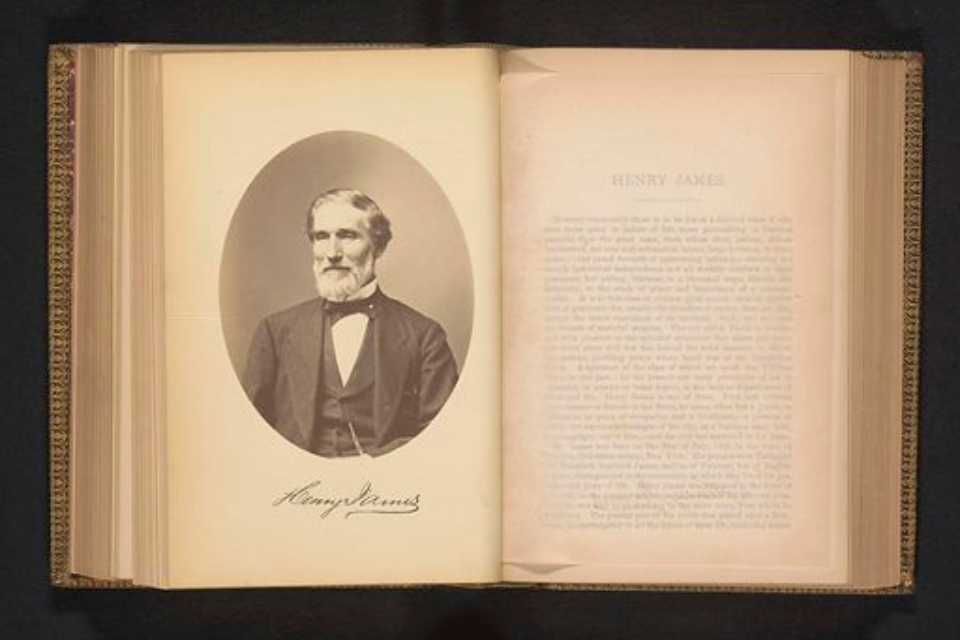

Photo Credit: Rijksmuseum

By Sam Gee

On Sept. 15 of 2023, the New Yorker published an exposé on the comedian Hasan Minhaj, revealing that much of the material in his stand-up comedy sets was fabricated. For instance, after criticizing the Saudi killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi, Minhaj claimed to have received a letter that, upon being opened, poured out white powder on his daughter, who had to be rushed to the hospital for fear of anthrax poisoning. According to Clare Malone, the author of the New Yorker piece, this incident never happened. In another instance, Minhaj said in a comedy special that a white high school girl had humiliatingly jilted him on the night of prom because of her family’s racism. Not only was this too a fabrication, but Minhaj failed adequately to conceal the alleged offender’s identity. Because of this, she received severe online harassment from Minhaj’s fans. When confronted by Malone about his deceptions, Minhaj defended himself by arguing that he had never really lied: his statements, while literally untrue, embodied “emotional truths” recognizable by other victims of prejudice in the United States. In comedy, “the emotional truth is first. The factual truth is second,” Minhaj contended.

No matter how unfortunate for those involved, the timing of the scandal couldn’t have been better – for just a few days later, students in my BOLLI study group “The Madness of Art: Henry James’s Shorter Fiction” were discussing Henry James’s short story “The Liar.” In this tale, a young, talented painter by the name of Oliver Lyon becomes obsessed with an old flame’s new husband, one Colonel Capadose, who has the unusual trait of compulsively telling incredible lies. Capadose’s lies are harmless exaggerations — his friends find his fibbing charming. But Lyon becomes strangely incensed by Capadose’s habit. By the story’s end, he engineers a situation in which Capadose and his wife Everina tell a lie that impugns another (innocent) person. Lyon feels vindicated, having proven to himself that Capadose’s lying was not merely an innocent quirk – but in the process, Lyon himself has deceived both Capadose and his former love Everina, becoming at least as morally ambiguous as Capadose himself.

In reflecting on his obsession, Lyon wonders whether as an artist he is also guilty of embellishing reality, and so of deception. Capadose, he thinks, is “the liar platonic… he’s disinterested… he doesn’t operate with a hope of gain or with a desire to injure. It’s art for art — he’s prompted by some love of beauty. He has an inner vision of what might have been, of what ought to be, and he helps on the good cause by the simple substitution of a shade. He lays on colour, as it were, and what less do I do myself?” Both Capadose and Lyon “lie” for the sake of “art.” James implicitly asks his readers to examine these lies and the men who tell them, to wonder whether departures from fact for the sake of artistic beauty or perfection could ever be morally justifiable.

In my BOLLI course, through reading stories like “The Liar” and other short works by the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century writer Henry James, I wanted to encourage participants to reflect on precisely the sorts of questions the Minhaj exposé raised. Is the pursuit of artistic excellence a moral good? Do artists have ethical obligations to living individuals? To dead individuals? Might looking at other people as material for artistic projects – novels, stories, paintings, comedy sets — blind an artist to the claims of others for respect and solidarity? Most broadly: what is the relationship between art and ethics?

Henry James is a particularly valuable author for discussing these thorny questions, and our discussions were informed by our introductory exploration of James’s biography. While James is sometimes seen as the artistic formalist par excellence, an aesthete who jettisoned the religious and moral baggage of his nineteenth-century American past and turned to the rich world of European fine art, this is in fact a misleading portrait. In the 1880s, James had tried his hands at a couple of political novels, and (in his own day’s judgment) failed badly. He had attempted to rehabilitate his career by writing and staging plays, but these bombed as well. At the same time, his mother and father died, severing his last meaningful connection to his American homeland. In the wake of such personal and professional tragedies and setbacks, James turned inward, meditating on the value of a life spent in literature. His short fiction of the later 1880s and 1890s, tales such as “The Lesson of the Master” and “The Real Thing,” as well as the great novella The Aspern Papers, would become some of James’s most enduring work. In these texts, James scrutinized the pretensions of art and artists, investigating whether a life devoted to the pursuit of beauty and artistic form could truly be a good life.

Readers familiar with James will know that he is a master of subtlety and ambiguity, as well as the most (in)famous connoisseur of the “unreliable narrator.” So part of our task in the study group was learning how to read a James story. In our discussions, we invariably began at the beginning, closely reading the first paragraph of each text to search for small hints in syntax, word choice, or tone — anything to give us a clue to discovering the direction in which James was trying to lead us. Having established our method, we continued closely reading the stories, pausing over sections that seemed especially significant or puzzling.

One tool we used to good effect was the simple one of reading aloud. The word on a page is mere ink; even when we read silently in our heads, words and sentences only assume meaning for us as we intone them, giving them — usually unconsciously — a certain inflection and emphasis. Reading out loud forces the reader to make choices. Is this sentence ironic? Is there pathos in that one? Is Ms. Ambient being mocked? Does the narrator accord a begrudging respect to Greville Fane? At the very least, when participants read passages of the text, we were all made to re-attend to those selections, and thereby enabled to pick up on small complexities we had not previously noticed.

Over time, we began to collect recurring images, characterizations, and themes. Many of James’s narrators in the stories of his “middle years” are young men with high artistic aspirations but only middling success; they seem to be motivated by a mixture of idealism and envy, wishing to contribute something beautiful to the world but constrained by the market to view every other artist and critic as competition. Many of these men, in their quest for aesthetic fulfillment, become obsessed — with writing a perfect novel, or finding out an artist’s secret intention, or gaining access to a trove of hidden letters by a great poet. In many cases, the narrator is revealed to be blinded by his own ideals, harming other people and depriving himself of love and fellowship in his single-minded passion for artistic purity. For James, we concluded, it was not so obvious that art and morality could be easily squared. And sometimes, it would seem, James seemed to suggest that our commitments to other people, and a respect for their dignity and autonomy, should outweigh our aesthetic dreams.

Of course, most of us in the study group were not professional artists. Our final question in the course was what any of this had to do with our own lives. Naturally there were no universally applicable answers here. I hoped to show, though, that James’s art parables were in some way relevant to all of us — that they were not just well-crafted and amusing stories. In James, the artist is anyone who becomes, in a Jamesean phrase, “violated by an idea” — anyone who is willing to put their own quests for self-fulfillment, self-realization, or self-perfection above the claims of others. James shows how easy it is for us all to rationalize such a maneuver, to believe that our own goals and ideals possess some sort of ultimate significance that make other people’s existences a mere inconvenience. The American critic Lionel Trilling once called this James’s “moral realism” — his awareness of the ways in which people can, with the best intentions and a good conscience, nevertheless do great wrong to others. For James, then, the artist is the avatar of moral realism — the artist is all of us.

This study group was conceived of as the second in a sequence of classes on classic American writers who embrace profound moral complexity. The first was on Nathaniel Hawthorne. In both of these classes, BOLLI learners enthusiastically embraced the tasks of close reading and deep thinking. The joy of teaching at BOLLI is that the study group participants have such a diversity and wealth of background and experience. In the James course, we heard from former psychologists, lawyers, teachers, librarians, and many others, all of whom had a unique perspective on the stories informed by their own particular lives. While an instructor’s claim that (s)he has learned as much from the students as they have learned from him or her is a platitude, at BOLLI, in my experience, it is also a truth — and not just an emotional one.

Sam Gee is a doctoral candidate in the University of Chicago’s Committee on Social Thought, where he studies American intellectual history and literature. His writing on these and other subjects has appeared in The American Scholar, The Point, The LA Review of Books, The Hopkins Review, Literary Imagination and other venues. This essay is based on Sams’ experience leading “The Madness of Art: The Short Stories of Henry James” at BOLLI in fall 2023.