Building a Strong Jewish Feminism from the Ground Up

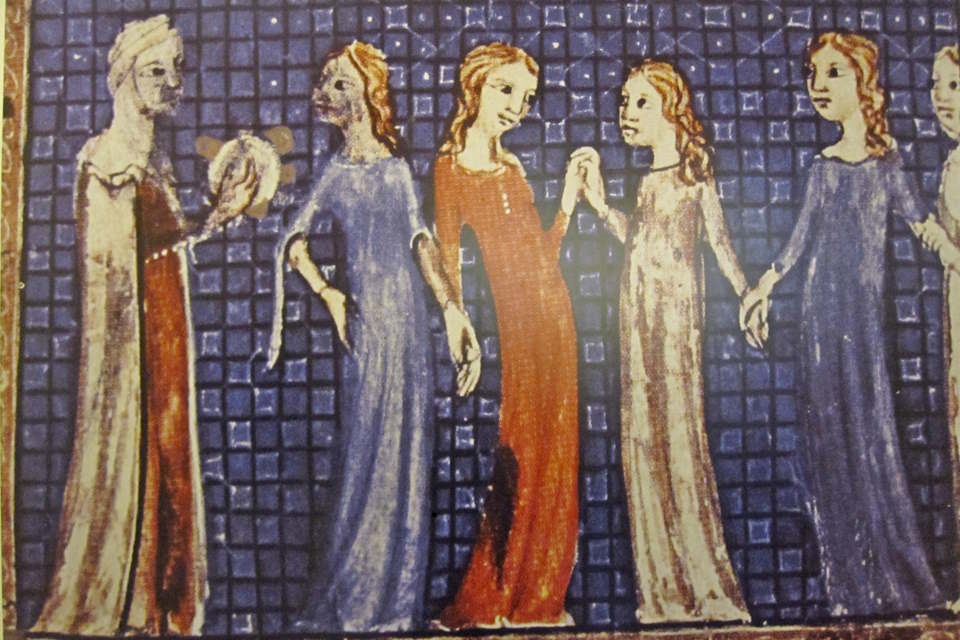

Illustration from the 14th-century Sarajevo Haggadah of Miriam (far left), the sister of Moses in the book of Exodus, holding a timbrel.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

April 5, 2023

By Julia M. KleinSurveying the publishing industry in the early 1970s, Susan Weidman Schneider '65 had a depressing realization: With the exception of an academic journal, "there were no Jewish magazines edited by women."

In 1976, Weidman Schneider co-founded Lilith, which describes itself as "independent, Jewish, and frankly feminist." As the magazine's first (and only) editor-in-chief, Weidman Schneider has published hundreds of essays, short stories, poems and articles exploring the intersection of Judaism and feminism.

Weidman Schneider

Weidman Schneider

With 5,000 print subscribers, tens of thousands of digital readers, and about 100 salons that meet to talk about each new quarterly issue, the magazine is "small but mighty," Weidman Schneider said.

Lilith has been "an opportunity to spotlight feminist change in the Jewish world and at the same time deal with the particularities of being Jewish and female," she said.

The Supreme Court's overturning of Roe v. Wade last year and new state laws limiting abortion rights roused Lilith's feminist fervor. An article characterized the anti-choice movement as "bad news for Jews."

"This is such a blow, such a turnaround," Weidman Schneider said. "I'm old enough to remember what it was like to have Brandeis classmates terrified that they might be pregnant with no access to safe and legal abortion."

Weidman Schneider has authored three books, "Jewish and Female" (1984), "Intermarriage" (1989) and, with Arthur B. C. Drache '61, "Head and Heart: A Woman's Guide to Financial Independence" (1991). Her numerous honors include the Joseph Polakoff Lifetime Achievement Award of the American Jewish Press Association (2000), the "Woman Who Dared" award from the National Council of Jewish Women (2008), and the Brandeis Alumni Achievement Award (2015).

Last year, Brandeis University Press published "Frankly Feminist: Short Stories by Jewish Women from Lilith Magazine" co-edited by Weidman Schneider and Lilith's longtime fiction editor, Yona Zeldis McDonough. The collection features 44 short stories grouped thematically under headings such as "Transitions," "Intimacies," and "War."

The stories' diverse settings, including 19th-century Persia, 1940s Europe, Israel, Las Vegas, and Manhattan, show what Weidman Schneider terms "the parallel struggles for women all over" the world on issues such as reproductive justice and autonomy. The stories “all feel very modern" and share "a certain open-endedness," she said.

The Shock and Thrill of Brandeis

Weidman Schneider grew up in Winnipeg, Canada, schooled in Shakespeare, grounded in Judaism, and largely apolitical.

She learned one of her guiding principles — "just because it's different doesn't mean it's wrong" — from her late mother, an actress, director, and playwright.

"Granted, this was spoken by a woman who thought it was very wrong if your slip showed," Weidman Schneider quipped. "But, aside from those sartorial dicta, she was very open to new forms in the arts, and that's been very helpful."

As a high school student, Weidman Schneider was active in her synagogue and a Jewish youth group. Brandeis' political ferment came as something of a shock.

"I arrived from my little Anglophilic universe with my hosiery and my pumps and gloves and was absolutely startled to find people in their dungarees and turtlenecks sitting around the reflecting pool, strumming guitar, singing protest songs," she said. "It was very thrilling."

Weidman Schneider majored in English and American literature, tutored students in Roxbury, Massachusetts, and attended anti-war marches — what she describes as "mild-mannered political protesting."

Israel Made Her a Feminist

She dates her feminist awakening to the late 1960s. Married in 1969 to a physician, Bruce Schneider, she had the first of her three children (including Rachel Schneider '95) shortly afterward. She experienced a feminist "ah-hah" moment during a six-month stay in Israel, where daycare was excellent and widely available, and there was "no opprobrium" attached to women working outside the home, she said.

Back in New York, where she still lives, Weidman Schneider began speaking and writing on the contrasts between Israeli and U.S. society. "Sometimes, I would sit in the playpen with a typewriter," she recalled.

In its early years, many of Lilith's articles involved "looking back," Weidman Schneider said. "There was a lot of ancestor worship, bubbe [grandmother in Yiddish] stories." Over time, the emphasis shifted. "As our writers became bolder, the scrutiny moved from the lives of our ancestors to our own lives," she said.

The magazine published ground-breaking reporting on abuse in Jewish families and rabbinic sexual misconduct. Lilith also was ahead of its time in covering sexual minorities, turning its pages over to trans-Jews a quarter century ago. "We've always believed in letting people speak for themselves, striving to have the tent as big as possible, understanding the pleasures of the ways people are different," Weidman Schneider said.

Lilith Today

The winter 2023 issue features the debut of several writers over 40. "Lilith believes in nurturing talent at any age," an introductory note says.

One memorable essay explores the dilemma of how to dispose of a Nazi dagger given to the writer's mother by a soldier as a bizarre token of his love. Another deals with the legacy of being a pornographer's daughter.

"I've come to understand that women in Jewish life have had subversive ways of transmitting their experiences and their stories," Weidman Schneider said. "There are even Yiddish songs of resistance, for example, telling of oppression from the outside world and also within families and communities."

Both Jews and women often find themselves in "that interesting marginal place, standing at the periphery of society" — a position, she said, that allows you both to "see a lot of what's going on and perceive it a little differently."