Aaron Goldberg's Quest to Save a Precious Jewish Mural in Vermont

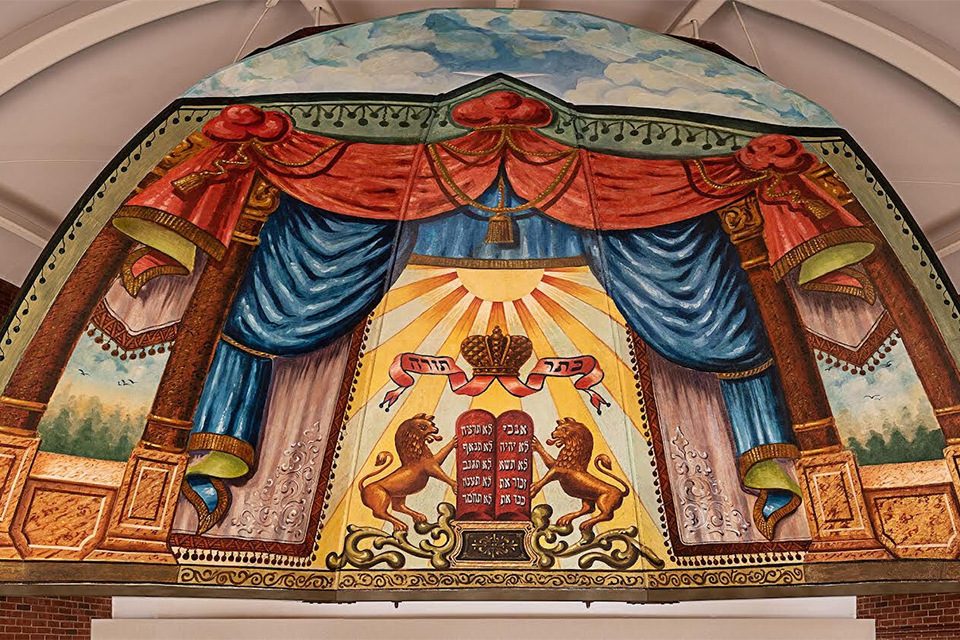

The Lost Mural hanging in Goldberg’s synagogue, Ohavi Zedek.

Photo Credit: Courtesy Goldberg

June 21, 2023

By Penny Schwartz, P'13In the summer of 1974, before his first year at Brandeis, Aaron Goldberg '79 stopped by a popular carpet shop in his hometown, Burlington, Vermont, to pick up a rug for his dorm room.

He spotted an old, faded mural on a wall inside the shop that seemed completely out of place. It depicted a series of traditional Jewish religious themes and symbols: a pair of lions symbolizing the biblical tribe of Judah, flanking the tablets of the Ten Commandments; a crown with ribbons inscribed with Hebrew words; and above it all, a sun emanating golden rays.

Goldberg had an inkling that the painting might be a forgotten relic of the city's Jewish immigrant past.

Some 50 years later, thanks to the combined efforts of Goldberg, conservationists, and many others, the mural now hangs in Goldberg’s synagogue, Ohavi Zedek, in Burlington, fully restored to its original glory.

It is one of the few surviving examples of early 20th-century American synagogue murals.

The Lost Mural, as it is now known, is the work of Ben Zion Black, a Lithuanian Jewish immigrant artist, mandolin orchestra leader, theatrical producer, and all-around impresario who immigrated to Burlington. He was hired in 1910 to paint the mural for the city's Chai Adam synagogue.

Black's style and imagery connected America's Jewish immigrant worshipers to wooden Eastern European synagogues, which had been adorned with similarly colorful and intricately painted interiors since the 18th century. Most of these synagogues — and the precious artworks inside — were destroyed by the Soviet Union and Nazis.

In 1939, Chai Adam merged with Ohavi Zedek, leaving the 11-foot high, 21-foot wide, and 9-foot deep mural behind. In 1970, the building became Harry Wheel's Carpet Gallery. Wheel was a devout Catholic, but his son-in-law wanted the Black mural preserved because, he said, it "spoke to him."

Goldberg at Brandeis

As an American studies major, Goldberg immersed himself in American immigrant, social, and religious history. As part of his research during college, he conducted scores of interviews with Burlington's Jewish residents about their experiences and the city's past. His own maternal ancestors were among the first wave of Lithuanian Jewish immigrants settling on the shores of Vermont's Lake Champlain.

After graduating from law school, he returned to Burlington to practice law and raise a family with his wife, Rebecca London Goldberg '79.

In 1985, Aaron Goldberg and his lifelong friend, historian Jeff Potash, organized Ohavi Zedek's yearlong centennial celebration. They delved into archival material that later became the foundation for the award-winning Vermont Public Television documentary "Little Jerusalem," also the name of Burlington's original Jewish neighborhood.

The Mural in Peril

In 1986, Goldberg learned that the rug shop where he'd spotted Black's mural was about to be converted into apartments. Goldberg said he and Potash acted to save the mural because it was an artistic expression of their city's place in the American Jewish immigrant experience.

"We didn't know then exactly what historical value it had," Goldberg said, "but we knew it was very important to save an iconic image from one of Burlington's synagogues."

He and several others founded Burlington Friends of the Lost Mural and persuaded the building's new owners not to destroy the mural. Instead, they received permission to frame and seal it behind a false plaster wall, hoping it could eventually be rescued.

They didn't have another look until 2010 when they opened the fake wall to inspect and photograph the mural. While it was still largely intact, they were dismayed by the paint damage caused by wall insulation placed too close to the mural.

So began the race against time to save the mural from destruction.

Goldberg, community members, and art and historic preservationists raised more than $1 million as part of an international campaign.

In 2015, in a feat of technical wonder, the mural was moved by crane and truck to Ohavi Zedek, two blocks away. A specially engineered steel frame was designed to extract, move, and display the Lost Mural. It also prevented the artwork from moving more than 1/100th of an inch in any direction during transport.

As part of the restoration, the conservator on the project discovered that the green drapery in the mural had been originally a royal blue, one of the primary colors of the tabernacle used by the ancient Israelites during their time in the wilderness in the Book of Exodus.

"The Lost Mural is a time portal, not just to 1910, but back to the Bible," Goldberg said.

The Mural on Display

Last year, hundreds of people participated in person and online in a ceremony that revealed the fully restored mural glowing in its original colors.

“We were incredulous," Goldberg said. "It was a joyous day for us and the community, a marvelous achievement."

Thousands of people from around the world, including the ambassadors from Israel and Lithuania, have since visited the mural. Last year, the project also garnered an award from the Preservation Trust of Vermont and has received international acclaim.

With the formal incorporation of the Lost Mural Project as a nonprofit in 2016, Goldberg has seen his save-the-mural project become a full-fledged community organization working with other nonprofits to present educational programs.

Goldberg is especially excited about the Lost Mural's outreach to Burlington's newer immigrant groups and Indigenous peoples.

Goldberg said the Lost Mural inspires people from other cultures and backgrounds to share their experiences and memories of their own cultural heritage.

"The mural has the power to speak and to tell multiple stories," he said. "That is rare and very precious."