5 Documents That Tell the Story of American Jewish History

August 16, 2022

By Joseph Dorman

In coming to America, the "people of the book," as the Jews are sometimes known, also became the people of documents.

In letters, contracts, laws and legislation, photographs, temple newsletters, and even advertisements for rye bread, the Jews' triumphs and travails were all recorded, reflected upon, and discussed.

"New Perspectives in American Jewish History," published last year by Brandeis University Press, gathers over 50 rare, little-known yet still seminal documents from American Jewish history, ranging from correspondence about the earliest known Jewish divorce in 1774 to a Black Lives Matter Haggadah in 2019.

The editors, the University of Cincinnati's Mark A. Raider, GSAS PhD'96, and Hebrew Union College's Gary Phillip Zola, put the book together as a tribute to their mentor and dissertation adviser, Brandeis professor Jonathan D. Sarna '75, GSAS MA'75, considered the preeminent scholar of American Jewish history. More than 30 academics and archivists, all former students of Sarna, helped select and annotate the documents.

"We offer our profound and heartfelt gratitude to our dedicated teacher Dr. Jonathan D. Sarna — a scholar's scholar, an extraordinary mentor, and a consummate mensch," Raider and Zola write in the introduction. "Your imprint on the field of American Jewish history is incalculable, and we are proud to call ourselves your students."

TJE chose five documents from the book and asked Sarna, the Joseph H. and Belle R. Braun Professor of American Jewish History and University Professor, to explain their significance.

Religious Freedom

Letter from President George Washington to the Hebrew Congregation of Newport, Rhode Island

In 1790, the newly inaugurated Washington wrote to the congregation Yeshuat Israel (later known as the Touro Synagogue) to provide his commitment that Jews would enjoy equal rights under the Constitution, ratified only two years earlier.

"All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship," Washington wrote. "... [H]appily the Government of the United States … gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance."

SARNA: The Jews wanted to know whether the lofty sentiments of America's founders applied to Jews. Washington guaranteed them that they did.

In Western Europe at this time, Jews were being granted rights, but it was a quid pro quo. In return, they had to change their ways. And if they didn't change, those rights would be taken away. But amazingly, Washington claims that religious liberty is an "inherent natural right," which means it cannot be taken away.

Protest and Advocacy

Letter from the Board of Delegates of American Israelites to the son of the Russian czar

In 1871, Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich (1850-1908), son of czar Alexander II, led a goodwill delegation to the United States.

The Board of Delegates of American Israelites, considered American Jewry's first political organization, wrote to him, pleading for him to improve the welfare of Russian Jews. "The good Czar, your father, encourages us to hope that every vestige of discrimination against the Jews of Russia will soon be swept away," the letter states.

SARNA: The Board of Delegates brought Jews together for the first time Jews as a political body. It shows how Jews were politically self-confident on the eve of the Civil War.

The Board's creation also suggested the Jewish community was large enough and self-confident enough to begin thinking about fighting for rights. And time and again, when Jews felt their rights were endangered, the Board was there for them.

Self-Policing

Boston Globe article, July 8, 1902

As millions of Jews came to this country between 1880-1920, men often arrived before their wives, hoping to earn enough money to bring their families over later. Some of the men had affairs, and some even tried to marry their lovers. The American press, always alert to juicy scandals, reported on these attempted bigamies.

One article in the Boston Globe described the recently married Motke from Warsaw, who sought to arrange a new marriage with an unsuspecting but well-off Jewish woman.

He was found out, and a "different" marriage was arranged for him. On his wedding day, he arrived to discover that his heavily veiled "bride" was a man in disguise. Along with some of the guests, the "bride" delivered 40 lashes to the malefactor with a barbed leather thong, the rabbinically prescribed punishment for such offenses.

SARNA: This story is about how Jewish immigrants punished one of their own, creating, in a sense, an internal community court to deal with his crimes. My Brandeis colleague, Albert Abramson Associate Professor of Holocaust Studies Laura Jokusch, has shown that after the Holocaust, internal Jewish courts sometimes similarly meted out punishment to Jews who were seen as Nazi collaborators.

The Boston Globe document reminds us that these courts have a much older history. Jews, after all, came from places where many had enjoyed substantial self-government. Immigrants felt empowered to do so in defense of Jews' good name.

Intermarriage

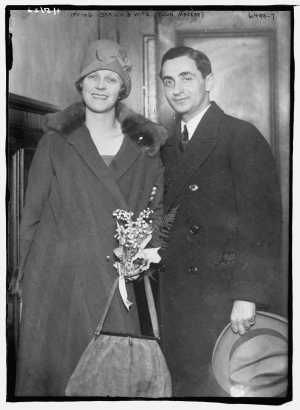

Photo of Irving Berlin and Ellin Mackay

Mackay and Berlin

Mackay and Berlin

When the great Jewish American songwriter Irving Berlin married Ellin Mackay in 1926, it was controversial inside and outside the Jewish community. She was from a wealthy, Republican — and Christian — family; he was a self-made Jewish immigrant whose songs, including "White Christmas," came to embody the essence of mainstream American culture.

SARNA: Here you are beginning to see a world where Jews are succeeding, but they are also falling in love with non-Jews. The Jewish community, even in the 1920s, is torn about this. They had to grapple with the fact that in a free country, people made free choices.

The power of America is that immigrants like Irving Berlin could get rich and produce songs that everybody would sing. But the risk was that a small minority group like the Jews could, through assimilation and intermarriage, disappear into the mainstream. This promise and danger characterized American Jewish life for the next century.

Everyone's Jewish Now

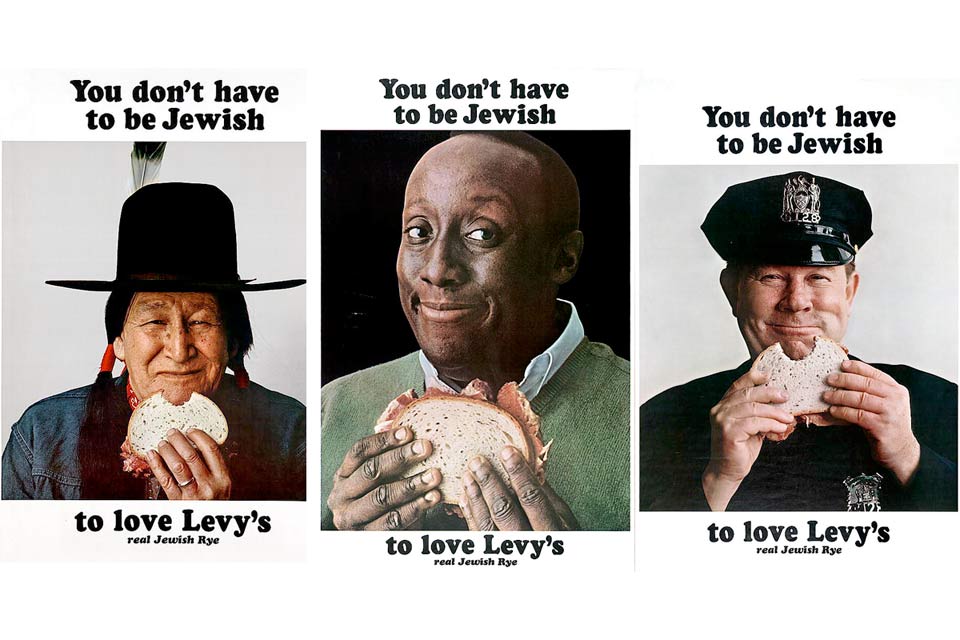

Ads for Levy's Real Jewish Rye Bread

In 1961, Levy's ran a hugely successful advertising campaign with the slogan, "You don't have to be Jewish to love Levy's real Jewish rye." The ads featured an iconic American — an Asian man, a Native American, a New York City cop and Buster Keaton, among others — eating a rye-bread sandwich.

SARNA: The powerful message underlying this ad campaign was that we all benefit from the presence in America of different racial and ethnic groups.

The Levy's ad played with a question inherent in the American motto, e pluribus unum, out of the many, one. What should be the relationship between the pluribus and the unum? That has long been an issue in American life, not just among Jews. This ad took a particular and very popular slant.

Today, we still need to think about ensuring that we are not just a pluribus of many competing and warring groups but also remain an unum – one unified country where people learn and borrow from one another.