Symposium Peregrinum 2024

Santa Maria Capua Vetere (Capua), Italy

June 11-13, 2024

History-Changing Prophecies:

Prophecy and Oracles that Did or Would Have Changed History – Real, Fictitious, and Fiction

SUBMIT YOUR ABSTRACT

Call for Papers 2024

Organizers: Francesca Ceci, Patricia A. Johnston, Attilio Mastrocinque,

Claudia Santi, Elena Santagati, and Gaius Stern

Prophecy in its multifaceted aspects will be the topic of the 2024 Symposium in Capua.

In the ancient Greek and Roman world prophecies influenced the course of history or failed to be influential and, even in this case, consequences ensued, at least in historical and political discourses. Understanding, misunderstanding, or not believing prophecy recurs as a theme in many famous literary and historical accounts, ranging from Cassandra in the Trojan War and in Aeschylus’s Agamemnon, Croesus causing a mighty empire to fall when he made war on the Persians, the foretold death of Cambyses in Ecbatana (Syria, Hdt. 3.64), the Theban quest for revenge on Athens (Hdt. 5.79-80), Athenians trusting in wooden walls against Xerxes (while a few fortified the Acropolis with a wooden wall), the people of Velletrae receiving an oracle that one of their citizens would rule the world, so they repeatedly fought Rome and lost centuries before Augustus was born (Suet. Div. Aug. 94.2), Father Liber and Nigidius Figulus on separate occasions telling Gaius Octavius (pr. 62) that his son would rule the world (Suet. Div. Aug. 94.5), Celaeno foretelling to the Trojans that hunger would force them to devour their very tables in Italy (Aen. 3.251-57), Delphi warning Nero to beware of the 73rd year (Suet. Nero 60.3), to the false and real prophecies of Alexander the Quack-Prophet in Lucian of Samosata and so on. The emotional and tragic style in history writing delighted in exploiting prophecies and in the expectation of their fulfillment. Thucydides and Polybius argued against such an historical style, although it was extremely popular among readers and had its first great model in the Histories of Herodotus (see Croesus, Cambyses, and the wooden walls above, but also how the Heraclids should have vengeance on the Mermnadae in five generations in Lydia, 1.13, Chilon of Lacedaemon warning Peisistratus’s father not to have a son, 1.59, etc.).

Joseph Fontenrose, The Delphic Oracle (1978) says that most surviving Delphic oracles were straightforward, but Herodotus has distorted how we think of them. Many true prophecies are known, but so are many ex eventu prophecies, i.e. invented prophecies. Political personalities or groups, and numerous historians concocted detailed prophecies pretending that they were uttered before the events, such as the many signs pointing to Augustus and later to Vespasian as rulers of Rome. The stories of vague and ambiguous prophecies, open to different or even antithetic interpretations are better known. And some were unclear in order to give the oracle an escapeway in case of a mistake.

Greek historiography, poetry, and literature generously deal with prophecies at some turning points of history or literary plots, especially in tragedies. The Roman authors followed both the Greek model of “dramatic historiography” and that of “factual historiography” by giving different roles to prophecies. The Romans and Italic peoples had a different approach to prophecy. They resorted rarely to famous Greek oracles, and especially that of Delphi, but often consulted the oracles of sortes, based on lot by means of knucklebones and collection of short oracular texts just called sortes. The libri Sibyllini were often consulted in Rome to obtain pieces of advice by Apollo. The sortes Praenestinae were extremely famous but almost every city in Italy had its own collection of sortes. We know little of the content of these little prophetic texts and the few preserved sortes are mostly ambiguous and simple pieces of advice. The task of interpreting these divine answers fell on experts and priests such as the Roman decemviri sacris faciundis.

Lucian of Samosata, in his work Alexander, the False Prophet, unveiled the process of creation of an oracle by a clever man, which investigates the creation and spreading of fictitious oracles. The Roman government once organized a meticulous study of the Sybilline Books to cast out spurious prophecies. Phlegon of Tralles collected oracles and prophecies set up in the Hadrianic period when the reliability of oracles was discussed and questioned. Even later, the emperor Julian (r. 361-63), tried to restore the status of many of the oracles of polytheist Greece and Rome, which had been persecuted under his immediate predecessors.

Prophecy was a major attribute of the god Apollo in both Greece and Italy. Many events in history, literature, and mythology hinged upon a consultation with the gods to obtain a favorable prophecy governing personal or political decisions. In the Iliad, many characters are able to prophesy the destruction of Troy or, in a few cases, the deaths of famous individuals (Calchas, Achilles’ talking horse Xanthus, etc.), but several fail to foretell their own deaths in the Trojan War, even as they warn their comrades of their demise (starting with Merops and his sons Adrastus and Amphius, Il. 2.830 ff.). Some prophecies fail to come true. Cornelius Lentulus heard that three Cornelii would rule Rome and expected to be the third, after Cinna and Sulla, but Cicero executed him. Hadrian executed two possible rivals “fated to be emperor” (HSA Hadr. 23.2). Was Apollo at fault here for failing to prophesy the future correctly, or did mankind find a way to foil destiny? Some other unlikely individuals rose to power, such as Agathocles tyrant of Syracuse (a penniless but talented wretch), Claudius, and Vespasian (both younger brothers). Hermes first told Circe that Odysseus would prove immune to her magic tricks and then, years later, intervened to give his great-grandson moly (mandrake) with which he invalidated Circe’s spells. Tiberius had heard the prophecy that Galba would rule Rome in his old age, but decided not to execute him because it would happen long after Tiberius had died. Did Apollo change Tiberius’s mind to ensure the validity of his own prophecy?

In many stories in epic literature and mythology, hearing a prophecy about parricide or an overthrow, an individual tried to change the future by exposing an infant. The child always survives to fulfill the prophecy (Acrisius, Jason, Oedipus, Paris, Cyrus the Great, Romulus and Remus, etc.), and these prophecies changed history every time. In literature, exposing a newborn never works; in real life, a bear or wolf almost always eats the baby. How do infants of prophecy beat the odds? We are curious to hear your thoughts on prophecies that changed the story (mythological or literary) if fictional or history if it was real. This year we will entertain topics pertinent only to the Greeks, Romans, Etruscans, and peoples that have important relationships with them. The conference proceedings will be published, hopefully in 2025. For those who are unable to come to Italy, there will probably be a Zoom session. If Gaius is unlikely to come to Italy, he will again organize those sessions.

The Symposium 2024 will meet in Santa Maria Capua Vetere at L'Università degli Studi della Campania Luigi Vanvitelli and may include one session in Caserta, outside Naples, either in the royal palace or in a seat of the University. Excursions will be organized to visit sites in and near Santa Maria Capua Vetere. Capua is an important archaeological and historical site where an amphitheater, a Mithraeum, and an ancient gate (the Arch of Hadrian) are located. An interesting museum is in Caserta and another two in Capua. Very near are a large range of other Roman sites: Nola is 29 km away; Herculaneum 40 km away, and Pompeii just 55 km.

Deadline:

15 April 2024 midnight CA time. Please send abstracts in English by 31 March so that we can figure out if we have enough participants to add June 10 for more papers.

All conference papers will be read in English. If you need help translating into English, Gaius and Patricia will help you translate (for free) before the conference. Please do not wait until the last minute to take advantage of this offer. Publications in English now reach a wider audience than in any other language. Therefore, it is wise to publish in English. Please feel free to contact the organizers with questions.

Getting to Santa Maria Capua Vetere:

You can fly into Naples or Rome and take a bus or train to a SMCV. Trains from the Naples airport are about 1 hr 10 min with one change of lines. From the Fiumicino airport, one must ride to Termini and change trains to go to SMCV, the journey is about 2 ½ hrs if one takes the faster train to Termini.

Ciao!

Francesca, Patricia, Attilio, Elena, Claudia, Gaius, Laszlo

History of the Symposium Peregrinum

These Symposia began in 2013, and many of the collected papers have been published by Acta Antiqua in Hungary. Before that, they were "Symposia Cumana--held at the Villa Vergiliana for the Vergilian Society. Now we move around Europe--hence the name "Peregrina." Many of the earlier collections were also published in Acta Antiqua.

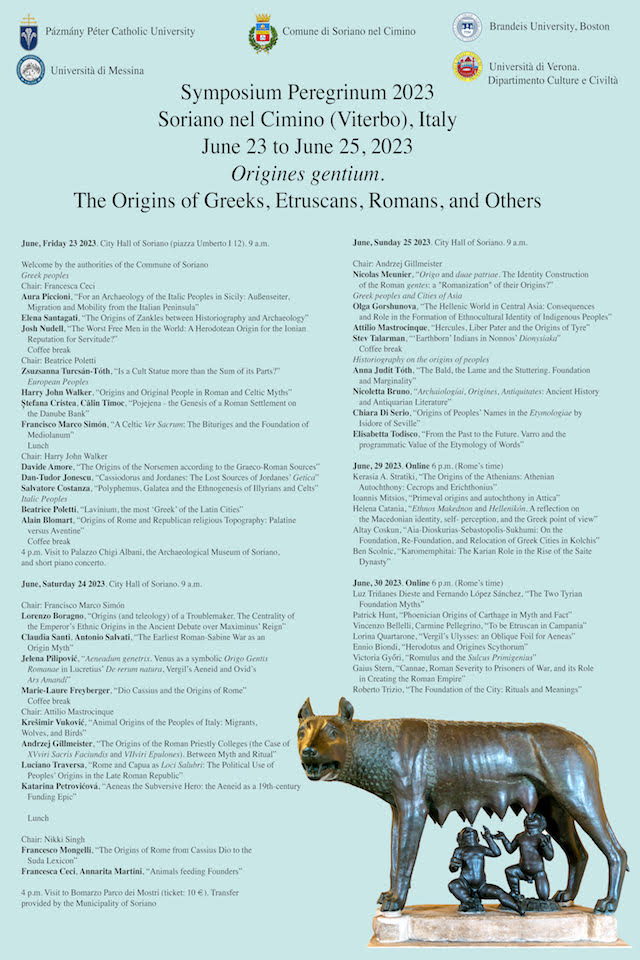

Abstracts for Symposium Peregrinum 2023

- Eran Almagor, “Solon and Lycurgus: Plutarch on the Origins of Athenian and Spartan

Constitutions and National Characters”

eranalmagor@gmail.com (Jerusalem) Zoom

Plutarch examined the origins of the Spartan and Athenian constitutions, the legislative projects, the two cities’ constitutions in their prime, as well as the seeds for their respective decline and demise in Lycurgus and Solon, respectively. Plutarch displays the activities of the two and the constitutional changes they brought as similes for the national characters of the citizens of their cities. For instance, the prominent feature of the Spartans according to Plutarch, is their seclusion. Yet, isolation also places the Spartans in a position where they can choose whether or not to interfere in the affairs of the rest of Greece, according to their own self-interest. This is the famous image of Sparta wavering between seclusion and ventures distant from home. This indecisiveness has its origins in the Spartan polity and its circumstances, as presented in the biography of Lycurgus. The Spartan lawmaker wished to maintain the Spartans’ seclusion by prohibiting them from living abroad so that they would not learn or imitate foreign traditions (Lyc. 27.3) and he made the people pledge not to change his constitution until he returned from consulting the oracle at Delphi (Lyc. 29.3). Lycurgus himself never came back (Lyc. 29.4).Yet, Plutarch also relates that Lycurgus’ remains were brought home (Lyc. 31.3), thereby ostensibly releasing the people from their oath.

Similarly, there is a subtle link between Athenian imperialism and democratic façade. Solon’s position of commander in the campaign against Salamis was gained through feigning madness and a public recitation of his poem “Salamis” (Sol. 8.1–2). His standing as legislator was also obtained by trickery (Sol. 14.2). Furthermore, the people would also pretend to be ostensibly obeying the laws, but in fact would wait for a change in constitution (Sol. 29.1).

2. Davide S. Amore, “The Origins of the Norsemen According to the Graeco-Roman

Sources”

davideamore@icsdannunziomotta.it I.C. "G. D'Annunzio" SISR

The Norsemen have been a source of fascination and mystery for centuries. Their origins and early history have been the subject of much debate, and numerous theories attempt to explain their cultural and ethnic roots. Greco-Roman tradition, one of the most influential sources of information on the Norsemen, provides valuable insights into the perceptions and attitudes of these seafaring warriors in the ancient world. Greek and Roman sources regarded the Norsemen as a mysterious and terrifying people, known for their brutal raids and conquests along the coastlines of Europe and the Mediterranean. However, despite the fear they inspired, these sources also provide valuable information on the cultural and ethnic origins of the Norsemen, shedding light on their beliefs, customs, and social structure. One of the earliest accounts of the Norsemen comes from Herodotus, who wrote about the Scythians, a group of nomadic warriors who inhabited the region near the Black Sea. Although the identity of the Scythians and the Norsemen is still a matter of debate, some scholars believe they have found many similarities between the two groups, including their seafaring abilities, their reputation as fearsome warriors, and their warrior culture. Tacitus also wrote about the Germanic tribes in his famous Germania. He provides a comprehensive overview of the customs and beliefs of the Germanic tribes, including the Norsemen, and offers valuable insights into their cultural and ethnic origins. He describes their warrior culture, their religious beliefs, and their social structure, and mentions the importance of shipbuilding and seafaring in their lives. While much of the information contained in Greek and Roman sources must be approached with caution, they remain an important part of the historical record, providing valuable insights into one of the most fascinating and mysterious peoples of the ancient world.

3. Vincenzo Bellelli – Carmine Pellegrino, “To be Etruscan in Campania”

vincenzo.bellelli@cultura.gov.it; cpellegrino@unisa.it

Parco Archeologico di Cerveteri e Tarquinia Zoom

The written sources record the domination of the Etruscans over a large part of Campania, i.e. the area between the Campanian plain and the Sarno river Valley, and the Agro Picentino in the Gulf of Salerno. Ancient authors refer to the period between the sixth and the first half of the fifth century BCE, as also suggested by the diffusion of Etruscan writing and bucchero pottery in this phase.

Our lecture intends to verify origin and nature of this Etruscan presence in the region. Recent studies have reduced the importance of migratory and colonization movements in the “Etruscanization” of the archaic period (the so-called “second colonization”). They have enhanced the political and cultural dimension of the phenomenon and the relationship with the urban structuring process of the local communities. In the Agro Picentino, the Etruscan paradigm has characterized Pontecagnano since the restructuring of the settlement in the last quarter of the eighth century BCE. Groups of different origins, coming above all from the Hirpinian hinterland, were integrated into the new political community. Nonetheless, the inscriptions testify to the use of the Etruscan language, and the most important aristocratic group gets its gentilic name (Rasunie) from the Etruscan autonym Rasna.

The development of Pontecagnano in the Orientalizing and Archaic Periods allows us to go back to the “Villanovan” origin of the center, and more generally to reflect on the presence of the Villanovan facies in the region.

4. Ennio Biondi, “Origines Scythorum, the Origin of the Scythians”

enniobiondi@hotmail.it Università di Catania Zoom

Herodotus 4.5-7 discusses the Origines Scythorum, relating a tale with very complex features. Our paper aims to search for meanings in the light of the Scytho- Iranian origin of the tale, but also according to the perception that Herodotus, a 5 th century Greek, had about these traditions with which he came into contact while studying the Scythian civilization. The theme of the first man and his sons, as recounted by Herodotus, has various parallels in the Indo-European world, probably connected with the Indo-Iranian trifunctional division of the society into sacred priests, warriors, economic operators. Other symbols of the story recall Iranian royal ideology. It is also uncertain whether there is a link between the three lineages and the geographical division of the Scythians into farmers, nomads and royalty. The story told by Herodotus reflects the dynamics between the various Scythian tribes in the moment in which struggles took place for the domination of large regions around the Dnieper River.

5. Alain Blomart, “Origins of Rome and Republican Religious Topography: Palatine versus

Aventine”

alaingfb@blanquerna.url.edu Ramon Llull University (Blanquerna – FPCEE), Barcelona, Spain

I will reflect on the symbolism of their topography of the temples of the Palatine and Aventine - two hills related to the origins of Rome, and I will explore the ideology that can be identified behind the divinities of these temples. Identifying values divinised or personified by these cults will allow us to understand the Roman ideology, because they refer to the earliest times in Rome, to its rural origins, to its struggles of power (social conflicts of the beginning of the Republic, political conflicts with peripheral people [Latin, Etruscans]), to its ideology of people coming from abroad and of conquering people, and to its fundamental values (victory, imperialism, moral values, etc).

I will conduct a historical and anthropological analysis of the Republican temples, classified chronologically: on the one hand, for the Palatine, the temples of Victory, Pales, Victoria Virgo, Magna Mater, Jupiter Invictus; on the other hand, for the Aventine, the temples of Diana, Ceres/Liber/Libera, Giunone Regina, Sol/Luna, Consus, Vertumnus, Minerva, Jupiter Libertas, Jupiter Fulgur, Flora. Finally, did these two hills present a historical, geographic, and social opposition, that is, was the Palatine the central, ancestral, aristocratic hill in contrast to the southern, peripherical and plebeian Aventine? More deeply, were the Palatine and the Aventine metaphors for conflict between city and periphery (which would explain the exclusion of Aventine out of the pomerium [the religious border of central Rome] at the Republic time, but also an opposition between aristocratic and plebeian power, between urban and rural area, between culture and wildness?

6. Lorenzo Boragno, “Origins (and teleology) of a Troublemaker: Maximinus Thrax.”

lorenzo.boragno@gmail.com École Française de Rome

The emperor Maximinus Thrax reigned in a turbulent era, at the beginning of a complex and rather obscure period. He rose through the ranks under Septimius Severus to usurp the imperial power by killing the last member of the dynasty of which he was for long a stalwart champion. His three-year reign (235-38 AD) began troublesome age: after his and his son’s tragic death, the empire plunged in a period of difficult wars and military defeats, plagues, political instability, and economic struggles. From a contemporary perspective the problems that plagued the Empire during the 3 rd century AD were rooted in Rome’s golden past, but for Greek and Roman historians, Maximinus represented a true turning point, the origin, and the cause of a true crisis.

Ancient historiography investigated causes and consequences seeking to understand from where or when evil entered the scene. However, while moderns might examine the ethnic origins of Maximinus, some ancient historians neglected completely the topic or rather focused on his social background.

I will examine these ancient historiographical narratives, highlighting in particular their deep teleological structures. As facts were carefully chosen and interpreted under the light of a moment in the “future past,” the ethnic element assumed dramatic role in historiographical narratives. Ethnic or social origins were therefore presented both to explains a series of events, as positive or negative stereotypes provided interpretative coordinates to shed light on personal or political motivations, and as omens of forthcoming events, or, as in the case of Maximinus, even as foreshadowing of much larger phenomena. Focusing simultaneously on the teleological structures of ancient narratives and on the intertextual dialogue between authors from different times and with different agendas, the present contribution aims to shed light on how causes, origins and the “future past” were intertwined in ancient historiography.

Maximinus “Thrax” stands therefore as a perfect case study. Did his reign anticipate, or cause the “Military Anarchy?” Looking more closely at the origins of Maximinus may perhaps help to understand the origins of this historiographic problem.

7. Nicoletta Bruno, “Archaiologíai, Origines, Antiquitates: Ancient History and

Antiquarian Literature”

nicoletta.bruno@wiko-greifswald.de Alfried Krupp Wissenschaftskolleg Greifswald, Germany

Archaiología was the Greek term for ‘antiquarian lore’ as distinguished from political and military ‘history’. Varro’s Latin translation Antiquitates became the familiar expression for this branch of indispensable knowledge, depreciated or overestimated at later times. Archaiología and antiquitas both mean ‘knowledge concerning the very ancient past.’ Arnaldo Momigliano pointed out that the main difference between historiographical work and antiquarian work was the diachronic vs. the synchronic approach. This clear-cut distinction between the ancient antiquary, who dealt with institutions, customs, and topography, and ancient history, which was concerned with past events, is substantially correct but oversimplifies it. Varro’s Antiquitates rerum divinarum et humanarum, was considered a work of antiquarian literature, but too little is known of this highly fragmentary work for us to determine Varro’s diachronic approach to history (Herklotz 2007). The term antiquarius, scarcely used in Republican and early Imperial Latin, means ‘one who appreciates archaic style and language’ (Tac. Dial. 37.2), a meaning curiously similar to the verb ἀρχαιολογέω, ‘to speak in an obsolete way, using an outmoded language’ (LSJ). Origines also can be associated with the Greek archaiologiai: linear chronological history, and a description of customs and institutions can be encountered in Cato’s Origines.

Clarke 2008 and Thomas 2019 have substantially revisited Felix Jacoby’s reconstruction of the development of historiography. Chaniotis 1988 and Thomas 2019 compiled substantial evidence from the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE about honors (honorary inscriptions) for historiographers, given communities, as they performed accounts of local history (often at festivals). According to Thomas 2019, an example of the local history of Rome that has come down to us intact and complete is Dionysius of Halicarnassus’ Ῥωμαικὴ Ἀρχαιολογία. Can we deduce that the antiquitates and the origines, by analogy, are local histories of Rome which contain chronological elements, political history, and cultural history, and what connects it with the Greek politeiai? A lexicographical analysis together with a close reading of selected passage will be a starting point for a new assessment on the subject and on the definition of Archaiologíai, Origines, and Antiquitates.

8. Helena Catania, “Ethnos Makedonon and Hellenikón. A Reflection on Macedonian

Identity, Self-Perception, and the Greek Point of View”

helena.catane@gmail.com Università di Messina Zoom

The concept of ethnicity is a particularly difficult issue: scholars have exploreddifferent areas to trace the specific characteristics of ancient ethnic groups and have been given different definitions, including one that understands ethnic identity as the sense of belonging to a specific group within a representation built on difference, on distinctive traits used to distinguish themselves. Starting from these considerations, the intention is to conduct a reflection on the Macedonian ethnical, political, religious and cultural identity and the Macedonian people’s self-perception as well as the way the Macedonians were perceived by other Greeks.

For this research there are many difficulties, since, first, literary and archaeological evidence, especially for older periods, is often controversial.

Therefore, the combined use of archaeological, literary and epigraphic data will be necessary to shed light on the perception that the Macedonians had of themselves and in their relationship with the Hellenikòn. Of the latter Herodotus 8.144.2 gives us a precise definition, identifying in the commonality of language, blood and places of worship, the general criteria of the Hellenism: it will be important, therefore, to try to understand if the inhabitants of Macedonia met these criteria – or tried to - or, if they chose others,what they actually were.

The reading of the sources on the origins of the kingdom of Macedonia and its perception in the eyes of the Greeks will also allow us to better understand the royal dynasty that will give birth to the figure of Alexander the Great, who will reinterpret the Hellenism, bringing it to the borders of the ancient world.

9. Francesca Ceci – host and co-organizer

Capitoline Museums

francesca.ceci@comune.roma.it (See the paper of Martini)

10. Altay Coşkun, “Aia – Dioskurias – Sebastopolis – Sukhumi: On the Foundation, Re-

Foundation, and Relocation of Greek Cities in Kolchis”

altay.coskun@uwaterloo.ca Waterloo University, Ontario Canada Zoom

Connecting a city’s origin with a glorious past, a powerful colonial history, or a mythical tradition were typical ways of bragging of certain qualities and, ultimately, claiming status into a later generation. It was not rare for the ancient Greeks to claim descent from a hero to underpin their pre-eminence among neighboring communities or to allege kinship (syngeneia) with a more powerful people whose alliance might be sought. The land of ancient Kolchis along the eastern Black Sea hosted various cities that competed for the rank of successor to Aia. Its famous king Aietes was the father of Medea, the wife of Jason the Argonaut.

The city most commonly accepted nowadays as ancient Aia is Kutaisi, formerly Kytaion, on the Rioni River in Georgia. But I have recently tried to show that the location of mythical Aia began to be envisioned in the eastern Black Sea region as a result of the Milesian colonization of the area in the 6 th century BCE. The first Greek city or emporion bragging its settlement in or by Aia was likely Dioskurias; Strabo 11.2.16.497–98C situates this ‘in the recess of the Euxine,’ which I identify with the Ochamchire area. Centuries later, Roman Sebastopolis claimed to be the successor to Dioskurias. Since Pliny NH 6.5.14–15 locates it at a distance of some 75 miles from Dioskurias, Sebastopolis was likely to be found at Skurcha by the Kodori river.

This contradicts the common opinion, which locates Dioskurias and Sebastopolis at Sukhumi further to the West. The earliest evidence for this is that the bishop of Sukhumi called himself “the bishop of Sebastopolis” by the 13 th century. More likely, however, this title was appropriated only after Sebastopolis had ceased to exist and the title could be transferred, in order to convey status within the Christian oikumene.

11. Salvatore Costanza, “Polyphemus, Galatea and the Ethnogenesis of the Illyrians

and Celts.”

salvicost@yahoo.it National and Capodistrian University of Athens, Greece

According to a mythical genealogy, the Sicilian Cyclops Polyphemus and Galatea were the parents of Illyrius, Celtus and Galas, the ancestors of the peoples named after them. This mythical story is related by second century historian Appian of Alexandria, Illyrike 2.3-4, the longest extant Greek source about the Illyrian world and the Roman conquests of the Western Balkans. In this case, the main source for Appian´s report is Timaeus of Tauromenium, whose fragment (FGrH 566 F69) is preserved by Etymologicum Magnum. This mythical aition goes back to Syracuse at the time of Dionysius I the Great. In particular, it seems useful for expansionist aims of the ambitious tyrant. In the Eastern Adriatic territories, Dionysius founded colonies, such as Issa in the island of Lissa (Viš) and supported the Parian colony of Pharos in the island of Lèsina (Hvar) against Illyrians. On either side, he promoted a symmachia, with the Celts employed as mercenaries by him and by his son Dionysius II the Younger. Dionysian propaganda was, thus, interested in claiming for the kinship of such peoples with the Hellenic world. Illyrians and Celts would be not merely Barbarians, but they would have a syngeneia with Greeks, given that their progenitors were born from the gamos of the Sicilian Cyclops with his beloved sea-nymph. As a result, cultural interaction was to be envisaged on the grounds of Syracusan primacy. Polyphemus plays a pivotal role, while another story lets Illyrios be the son of Cadmus and Harmonia, according to a different account of the Hellenization of the Illyrian world. It is noteworthy to examine which political purposes stay behind the genealogical motif attested by Timaeus and Appian and how the mythical figure of the Cyclops was enacted to serve this claim for the preeminence of Syracuse in the East Mediterranean, as literary sources allow us to understand better.

12. Ștefana Cristea and Călin Timoc, “Pojejena: the Genesis of a Roman Settlement on the

Banks of the Danube”

stefana.c.cristea@gmail.com, calintimoc@gmail.com National Museum of Banat, Romania

The setup and development of the Pojejena settlement is closely related to the foundation of the Roman fort, he proximity of the Danube, and thenearby mine (New Moldova). The Roman presence in the Iron Gates area, on the southern bank of the Danube, started in the 1st century AD, with several fortifications in the role of supporting and supervising navigation and ensuring the security of the limes.

During Domitian’s war with the Dacians, the Dacian fortifications from Socol, Pescari, Liubcova, and especially Divici dissolved. As a consequence the fort at Pojejena and the vicus arose. The fort passed through several phases of expansion, destruction, and restoration until Justinian’s time, influencing the setup of the port and vicus. The civil settlement had a much longer existence than the fort, continuing through medieval times to the modern period.

Archaeological research was carried out again, after a long break, in 2016, as small surveys, and in 2018 a Romanian-Polish team carried out non-invasive investigations (magnetometry and resistivity) that provided a complete picture of the camp and the vicus. The archaeological campaigns of 2019, 2020 and 2021 focused on the porta praetoria of the fort. The data provided by these campaigns gave important information about the origin and development of the fort and, by extension, of the civilian settlement. The archaeological campaign of 2022 approached for the first time the vicus, highlighting the richness and complexity of this settlement, as well as the existence of a Hallstatt period level.

Using all the data acquired from archaeological sources (old and new) and documentation we will expose the most important aspects of the rise of the Roman settlement at Pojejena: a Hallstattian habitation, the dissolution of the Dacian fortifications, the foundation of the Roman military fort, its location on the bank of the Danube, and the mines exploited from the Roman period.

13. Chiara Di Serio, “Origins of Peoples’ Names in the Etymologiae by Isidore of Seville”

diseriochiara111@gmail.com University of Cyprus, Cyprus

In his monumental work on the Etymologiae, Isidore of Seville illustrates the then known disciplines according to the conceptual model that the ultimate meaning of a name encompasses and represents the origin of what is named. Chapter II of Book IX illustrates the origin of peoples’ names. At the beginning of the chapter, Isidore provides a definition of gens. It constitutes a synthesis of Roman thought, which had reworked the Greek concept of genos, leading to the idea of nation. Isidore continues with a long list of peoples who would descend from Japheth, Ham and Shem, the sons of Noah. Within this long and rich list, Isidore follows a double path. First, he lists the peoples who would descend from the progeny of Japheth, Ham and Shem. Then, after explaining that the names of the peoples changed rationally, he lists again the same or other peoples whose names clearly show an assonance with those of the mythical founders or progenitors. With regard to this catalogue, the focus of this paper is the analysis of the names of eastern populations – such as the Indians, the Seres, the Bactrians, the Parthians, the Assyrians, the Medes, the Persians, and numerous others – among whom are also included some fabulous communities, such as the Amazons and the Ichthyophagi.

13. Marie-Laure Freyberger, “Dio Cassius and the Origins of Rome”

marie-laure.freyburger@uha.fr Université de Haute-Alsace, France

Cassius Dio wrote in Greek, at the beginning of the 3 rd century AD a Roman History which was composed of 80 books, from the origins until his own time. Unfortunately, the first books did not come down to us, and some of the next books are fragmentary (summaries or quotes of Dio’s writing). To know how Dio tells the origins of Rome, we have to refer to a Byzantine summary, preserved by Johannes Zonaras (11 th century) and to several fragments kept by later grammarians or lawyers. All these texts confirm that, for Dio, there is absolutely no doubt about the Trojan origins of Latium’s inhabitants.

14. Gerard Freyburger will attend but not present

gfreyb@unistra.fr

Université de Strasbourg, France

15. Andrzej Gillmeister, “The Origins of the Roman Priestly Colleges (the case of XVviri

Sacris Faciundis and VIIviri Epulones). Between Myth and Ritual”

a.gillmeister@ih.uz.zgora.pl University of Zielona Góra,. Poland

The Romans had a fetish for genesis. In a situation where the primary determinant of the accuracy of the religious activities being performed was their ancient origins, this approach seems logical, especially when embedded in civic mythology.

I would like to present the beginning of the formation of two priestly colleges: the XVviri Sacris Faciundis and the VIIviri Epulones. In the first case, I would like to focus on the figure of the infamous priest Marcus Atilius, sentenced to death for arbitrarily copying a fragment of the Sibylline Books. This was later used to create an aetiological myth to explain the origins of the role of the college.

In the case of the epulones, we are faced with a very different situation - the apparent absence of an origin mythology. But is it completely lost? The juxtaposition of two important priestly bodies will hopefully help to clarify their role in the Roman religious system and to nuance the myth of origines in ancient Rome.

16. Olga Gorshunova, “The Hellenic World in Central Asia: Consequences and Role in the

Formation of Ethnocultural Identity of Indigenous Peoples”

ogorshunova@gmail.com A.N. Kosygin MSTU, Russia

According to Quintus Curtius Rufus and Strabo, ancient Greeks settled in Central Asia in the 5th century BC. Greek migrations became more intense and led to significant changes in the ethnic situation and local cultures after Alexander the Great conquered the region (329-327 BC). Having defeated the Persians, Alexander annexed the East Persian satrapies - Parthia, Margiana, Bactria, and Sogdiana, spanning parts of modern Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. Later on, large Greek settlements and cities were founded, where, following the soldiers, Greek merchants, artisans, actors, sculptors, medalists, and musicians moved to stay forever. These migrations changed the ethnic composition of the population of the region, and the culture brought by the Greek settlers opened a new milestone in the history of Central Asia - Hellenism.

After the death of Alexander and the collapse of his empire, the Central Asian satrapies fell under the rule of the Seleucids (about 305 BC). During their reign, the Hellenization process reached its culmination, ensuring the dominance of the Hellenic traditions in all areas, from politics to art. By the end of the Seleucid rule in Central Asia, the Greek migrants and descendants of the early settlers have been largely integrated into the local environment, and a significant part of the local population had become adherents of the Hellenic culture. That is why in the middle of the 3rd century BC, when the Seleucids lost most of the Central Asian territories, and later, after the capture of Central Asia by nomadic tribes (Yueji) and Persians, the Hellenistic traditions retained their strength until the Arab conquest of Central Asia in the 7th-8th centuries.

Despite significant cultural and religious transformations as a result of the Arab conquest of Central Asia, legacies of Hellenism remain. An analysis of various sources, including materials obtained during my field work in the region indicate that the events of the Hellenistic period deeply influence the ethno-cultural identity of the indigenous Muslim peoples of Central Asia.

17. Vicky Győri, “An (Under)Valued Romulean Icon: The Sulcus Primigenius”

victoria.gyori@kcl.ac.uk University of Pécs, Hungary Zoom

Everyone agrees that the she-wolf with the twins, Romulus and Remus, and the tropaeophorus figure are the most enduring images of them. A third image of Romulus, however – the priestly figure with a plough referring to his ritual ploughing of Rome’s sacred boundary that marked the foundation of Rome (Plutarch, Rom. 11.2-3; cf. Livy 1.44.4) – became equally prevalent in Romulean mythology, particularly in the Roman provinces. Nevertheless, there is to date no artistic example of Romulus ploughing the sulcus primigenius (“original furrow”) and only a few reliefs of a ploughing scene in Roman art. The sulcus primigenius is the most common “Roman” type (other than depictions of the Roman imperial family) found on coinage minted by Roman colonies throughout the provinces. The images of the founder – usually the emperor – driving a yoke of oxen to plough the sulcus primigenius or of a plough were minted by almost every Roman colony from the Late Republic to the third century AD.

What was the significance of Romulus’ sulcus primigenius ritual, how and why did it become a crucial rite in the foundation of all Roman colonies? Dionysius of Halicarnassus 1.88 says that Romulus’ act was the model on which Romans founded colonies throughout the provinces. The urbs came into existence when it was encircled by the furrow drawn by a plough, for its foundation was dependent on the plough’s tangible contact with the earth which designated the pomerium (Varro LL 5.143). This ritual act defined, both physically and symbolically, the foundation of a city.

So the depiction of the sulcus primigenius ritual on Roman provincial coinage is fundamental to the justification and the promotion of the Roman identity of these colonies. First, the colony demonstrates its foundation according to mythical foundation of Rome by commemorating its “birthday” – it explicitly states it is Roman because the sulcus primigenius is a Roman urban foundation ritual. Second, the colony advertises perhaps the most Roman episode of Romulus’ life - the very moment Rome became the city of Rome when Romulus ploughed the original furrow.

18. Patrick Hunt, “Phoenician Origins of Carthage in Myth and Fact”

phunt@stanford.edu Stanford University Zoom

The legend of Dido (Elissa) cutting up the ox hide makes a winsome Phoenician origin myth for Carthage, however poeticized it must be as a beginning. There are likely kernels of historical reality in Vergil's interweaving and in Pompeius Trogus' use of dramatic details of Tyrian personae. The incipient historiography of Diodorus Siculus' Kulturgeschichte may not address Carthage's development, but perhaps more important is

that the topographic placement of Carthage (Qart Hadasht) is sensible for its locus and timing in Phoenician expansion in the Western Mediterranean even though it is not the first western Phoenician colony by any means but becomes arguably the most prominent and wealthy for logical reasons. Carthage's North African contexts and proximity to Sicily are certainly important in the development of Phoenician mercantilism and ultimately of Roman antagonism, as this presentation suggests.

19. Dan-Tudor Ionescu, “Cassiodorus and Jordanes: The Lost Sources of Jordanes’ Getica”

dan_tudor.ionescu@yahoo.com Metropolitan Library of Bucharest, Romania

Jordanes Getica, possibly used the lost Historia Gothorum (or Historia Getarum) of Cassiodorus and also the oral recordings from living memory of the old Ostrogoth warriors and noblemen from the time and royal court of king Theodoric the Great of the Ostrogoths and ruler of Italy, Noricum, and NW Dalmatia (r. AD 491-526). But Greek and Roman writers from the 4th - 7th centuries AD, roughly from the time of Eutropius to Isidor of Seville, who was writing in Visigothic Spain, confused (voluntarily or not) the Getae of Classical Antiquity and the Goths in Late Antiquity among.

I will uncover and analyze the origin of this confusion between two distinct peoples. The Northern Thracian\ Getae and the Eastern Germanic Goths had a common origin, but they parted probably in the Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age at the latest. Roman writers, however, beginning with Eutropius and the panegyrists of Constantine the Great in the 4th century AD, stated that Constantine, like Trajan (r. AD 98-117), had vanquished the Getae on the Lower Danube. In the first quarter of the 4th century AD, the dominant ethnos north of the Lower Danube were already the Gothic Tervingi, allied with the Sarmatian Roxolani and the Germanic Taifali and Victoali. The free Dacian tribes of the Carpi were also then part of the Gothic confederacy of the Tervingi. Later Roman sources equated the main ancestors of the Visigoths with the Dacian (Northern Thracian) Getae and Daci, free warriors that heroically, but ultimately unsuccessfully, defied the might of Rome. Modern historians consider this amalgamation to be largely, if not purely, propagandistic. I will argue that the idea of a lineage going back to the Daci and Getae legitimizes the Roman identification of the Getae with the Goths, so it was neither pure propaganda nor devoid of any truthful substance.

20. Patricia Johnston co-organizer Zoom

johnston@brandeis.edu

Brandeis University, (Massachussetts)

21. Fernando Lopez Sanchez & Maria de la luz Triñanes Dieste,

“The Two Tyrian Foundation Myths”

fernal06@ucm.es Complutense University of Madrid, Spain Zoom

Tyre had two types of foundation narratives. The first type is recorded in the Dionysiaca 40.467, a late antique epic of the 5th century by Nonnus of Panopolis and relates to Tyre, but also, it seems, to Gadir (in south Spain): Ambrosial Rocks and an olive tree originally floated in the sea before they were rooted to the sea floor, and the city was founded upon them. Tyrians seem to have adopted this narrative as their principal foundation story. The second type, prevalent in Carthage and Thebes, but also present at different times in Tyrian coinage, revolves around the central theme of a swimming bull carrying Europa with her billowing veil or about a bull, dead and cut off in stripes or fully alive, signaling the pomerium of the new city.

Tyre seems also to have employed mythical founders of Tyrian overseas settlements (oikistai), such as Dido in Carthage or Cadmus in Boeotia, in order to bolster its claims as a Phoenician metropolis negotiating with native populations in distant lands. Dido’s other name, for example, was Elissa, which also appears to be Phoenician in origin, perhaps meaning “wanderer,” Cadmus was the son of king Agenor of Tyre and Telephassa, and the brother of Europa, Phoenix, and Cilix. He was the founder of Thebes, originally called Cadmeia, meaning perhaps “East” from the same word that gave the name of the Saracens.

Unlike Tyre, Carthage, and Thebes each seem to have preferred different versions of the bull foundation myth. Tyre and Gadir, however, followed closely the Ambrosial Rocks prototype. Therefore, exploring the meaning of this foundation duality is not as straightforward as it looks at first sight. Coupled with literary and archaeological sources, Tyrian and Phoenician coins from Lebanon to Northern Africa, and from Southern Italy to Western Spain, provide also an interesting insight into how different Phoenician communities related to Tyre and defined their mythical past under changing political circumstances.

22. Francisco Marco Simón, A Celtic Ver Sacrum: the Bituriges and the

Foundation of Mediolanum.

marco@unizar.es University of Zaragoza / Research Group Hiberus, Spain

Livy (5, 34) explains the settlement of the Celts in Cisalpine Gaul through a migratory saga that he places in the time of Tarquinius Priscus. Ambigatus, king of the Bituriges, who had dominion over all the Celts, because of the surplus population in his prosperous kingdom sent his nephews Belovesus and Segovesus to lead the contingents they considered appropriate to settle in the places indicated by the gods. As a result of the drawing of lots, Segovesus headed for the forests of Hercynia, while the gods pointed Belovesus in the direction of Italy. Having helped the newly installed Phocaeans of Massilia against the Salians, the Celts crossed the Alps, defeated the Etruscans at the river Ticino and founded Mediolanum. For his part, the Vocontian historian Pompeius Trogo (in Justin’s Epitome 24.4.1 ff.) compares the Gallic migration to a “sacred spring;” (velut ver sacrum), in which one part of the expedition entered Italy and another, guided by birds, headed for Pannonia. This paper, which defends the historicity of the information and its consideration within an autochthonous tradition, analyses the cultural keys of this Wandersage carried out by the Gallic iuventus and its specific characteristics in relation to Celtic, Romano-Italic, and Greek parallels.

23. Annarita Martini and Francesca Ceci, “Images of Mythical Founders Suckled by an

Animal on Ancient Coinage and their Echo in the Carolingian World Symbolizing a

New Dynastic Kingdom”

annarita.martinicarbone@gmail.com Capitoline Museums, Rome Italy

Several humans in Greek and Roman literature and mythology were suckled by animals such as Cyrus the Great (according to Herodotus, but not Xenophon), Atlanta by a bear, and Telephos, ancestor of Capuans, by a deer, to mention just a few. Many ancient coins show an image on the reverse referring to a mythical hero, who later became a founder, but was first exposed and then suckled by an animal that nourished him, so that he then fulfills the destiny of glory that awaits him. This study focuses on the representation of arguably the most famous animal as a nurse: the she-wolf that suckled Romulus and Remus. This image recurs in Roman art and coinage down to the 4th century AD and even after.

The image of Romulus and Remus suckled by the she-wolf became typical on Roman coins, and its iconography conveyed in all the empire a fundamental political message. The importance of this iconography and its value in different media remained over the centuries. In the Middle Ages it was still used to affirm the foundation of a new potentate, especially in the 8th century. With the cultural renaissance linked to the ancient world, the she-wolf experienced a revival as a symbol of power. In Anglia, coins were minted with the image of Romulus and Remus suckled by the she-wolf, and in the court of Charlemagne in Aachen a suckling she wolf dominated. In both cases the suckling she-wolf represented the image of a new foundation of a dynastic kingdom.

24. Attilio Mastrocinque, “Hercules, Liber Pater and the Origins of Tyre”

attilio.mastrocinque@univr.it Università di Verona, Italy co-organizer

Hercules and Liber Pater (Herakles and Dionysos) were called dii patrii in Leptis Magna and Cuicul, in Libya. They also were patron gods of Septimius Severus, a native of Leptis. They were identified with two Phoenician-Punic gods, Milk‘ashtart and Shadrapha. The essential Greek origin of these dii patrii has been underlined by Edward Lipiński, who recognized their identification with Punic gods as a secondary feature. The choice of Heracles depended on the traditional identification of this god with Melqart, the divine lord of Tyre, homeland of Carthage. Milk‘ashtart was probably a different name of Melqart, worshipped along with Ashtart. The two deities, Hercules and Liber, still miss an explanation. A clue resides in the myths of Tyre and the mythic relationships between Greeks and Phoenicians. Tyre, and consequently Carthage, could have been proud for having been homeland of these gods. Herodotus testified to an early cult to Heracles in Tyre; the birthplace of this hero was Thebes, a city that Cadmos, a Phoenician king, founded. On the other hand, Dionysos was the son of Semele, daughter of Cadmos. Tyre and Carthage could claim priority in the cult of these outstanding gods thanks to the foundation myths of Tyre and Thebes.

25. Nicolas Meunier, “Origo and duae patriae. The Identity Construction of the Roman

gentes: a “Romanization” of their Origins?”

nicolas.meunier@uclouvain.be UCLouvain (Université catholique de Louvain), Belgium

The question of origins in ancient times does not only concern peoples: the “clans” (or gentes) did too, to a degree that appears underestimated by modern research. Many, indeed, are the great Roman families of the classical period who had a Latin or Italic (Sabine, Etruscan, Campanian...) origin of which they were perfectly conscious and which they even claimed sometimes (in particular on the coins). In the most ancient times, characterized by an important mobility (in particular of the elites) and by a geopolitical context where the hold of the Roman State on Latium and Italy was only in the course of formation, the identity definition of the gentes, and in particular the city to which they belonged (if there was only one), was much more complex than our sources (very late for the most part) allow us to believe at first reading. A re-reading of these sources, in the light of recent research on the archaic societies of central Italy, is necessary. The present paper will discuss the construction of the identity of several important gentes of the 6th - 4th centuries BC (Claudii, Quinctii, Manlii, Aemilii, essentially), highlighting their multiple identities (the “double fatherland,” duae patriae, which Cicero echoes), but also taking more into account the federal context of Latium prior to 340 BC, and attempting to clarify the process of a posteriori “Romanization” of the history of the ancestors of these clans.

26. Ioannis Mitsios, “Primeval origins and autochthony in Attica”

imitsios@arch.uoa.gr National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece Zoom

According to the literary tradition and iconographic evidence, most heroes who received cult worship on the Acropolis had a primeval origin and were connected with autochthony, such as Erechtheus and Kekrops. The Iliad 2.546-51 attests that Erechtheus was a son of the Earth, while Apollodorus 3.14.1 speaks of the diphyes nature of Kekrops, who was half-human and half-snake. In iconography also, Erechtheus is depicted in the famous ‘anodoi scenes” — shown delivered by his nurse, Ge, to his mother, Athena, and Kekrops also is a hybrid creature, half human, and half snake.

Thucydides 1.2.5 ( τὴν γοῦν Ἀττικὴν οὖσαν ἄνθρωποι ᾤκουν οἱ αὐτοὶ αἰεί) claims the Athenians are the only autochthonous Greeks. According to the Athenians, they and their mythical heroes were autochthonous, that is, always living in the same place. Herodotus 5.72 attests that the priestess of Athena Polias told the Spartan king Kleomenes at the entry to the shrine of Athena, “Go back, Lacedaemonian stranger, and do not enter the holy place since it is not lawful that Dorians should pass in here.” In Herodotus’ testimony the shrine of Athena symbolizes Athenian autochthony and identity.

This paper, by employing and interdisciplinary approach, will consider the literary sources, the iconographic and topographic evidence, and the identity aspects of the Athenian heroes who received cult on the Acropolis of Athens in close relation to the historical and ideological context with special emphasis on the ideology of autochthony.

27. Francesco Mongelli, “The Origins of Rome from Cassius Dio to the Suda

Lexicon” francesco.mongelli@uniba.it Università di Bari, Italy

As is well known, Cassius Dio, before writing his Roman History, wrote two works, one relating to the omens that had heralded the advent of Septimius Severus, another relating to the civil wars of the Severan age. Only after this experience the historian began the project of a “universal history” of Rome, in which he started from Rome’s mythical origins. However, Dio’s initial books are lost and we can only gain an idea of them through the fragments of indirect tradition, or through the works of Byzantine historiography that to a greater or lesser extent used Dio as a source (e.g. John of Antioch, Malala, George the Monk). This line of the tradition reaches its synthesis in the Suda Lexicon.

Among the best-known moments of Rome’s origins there is the account concerning the prodigious survival of Romulus and Remus through the intervention of the she-wolf; thanks to a quotation from Eustatius of Thessalonica, we know that Dio certainly narrated the episode, but we do not have further details. Byzantine historiography presents versions of the episode that differ in some respects; one of these versions also found its way into the Suda Lexicon, which, however, does not present a “monographic” entry devoted to Romulus or Remus (as it does, for example, for Numa Pompilius) but recalls the contours of the episode in entry β 556, in which it discusses Romulus’ institution of the festival of Βρουμάλια. This lecture tests whether the events narrated in Suda β 556 can in any way be traced back to Dio, in an attempt to recover a new fragment to the early books of the historian’s work. In addition, an attempt will be made to reflect on the chance that the historian’s recall of the events related to Romulus still had political significance during the Severan age.

28. Josh Nudell, “The Worst Free Men in the World: A Herodotean Origin for the Ionian

Reputation for Servitude?”

jpnudell@gmail.com Truman State University, Missouri

The perceived servility of Ionians is often taken as an irrefutable fact that shapes modern interpretations of Classical Ionia. Indeed, this reputation was well established at least by the early second century BCE when the Seleucid King Antiochus III declared to the Romans that the Ionians were accustomed to obedience to barbarian kings, and thus ought to be treated differently from the other Greeks (App. Syr. 3.12.1). Likewise, the proverbial prominence of Ionia that belonged sometime in the distant past can be found in the saying “long go the Milesians were powerful” (πάλαι ποτἦσαν ἄλκιμοι Μιλήσιοι, Athen. 12.26.523ff.), which meant “times have changed.”

Herodotus 4.118–43 provides the earliest possible evidence for this reputation in his account of Darius’ Scythian expedition. The Scythians responded to the Ionian decision to stick with Darius by hurling insults against the Ionians, calling them “master- loving slaves” and “the worst and most cowardly” free men (Hdt. 4.142). Indeed, Samons declares that “[t]he defense of Miltiades is thus bolstered by confirming the contemporary view that the Ionians were effete and inured to servitude” (2017: 37).

In this paper I address two interlocking questions. First, I will follow in the footsteps of recent scholarship that examines the sources Herodotus drew on for his presentation of individuals and peoples in his history (e.g. Blösel 2007; Irwin 2009; Samons 2017; Thomas 1989), with special attention to the context of the Athenian

Empire. Second, I will consider the legacy of this passage in subsequent presentations of Ionia, arguing that it played an outsized role in how late Archaic and Classical Ionia was understood. That is, where Samons argues that its inclusion reflects contemporary attitudes, I will argue that it planted a seed that confirmed later prejudices.

29. Giulia Pedrucci, “Back to the Roots of Ancient Sicily: The Role of the Anatolians in

Light of the Presence of Cybele in Prehistoric Times” Zoom

giulia.pedrucci@univr.it University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

“Back to the roots” has a double meaning: on the one hand, investigating the origins of the people who lived in Sicily before the historical and protohistoric evidence that refers to the Greek world; on the other hand, a personal return to the topic with which I began my academic career: the presence of the Anatolian goddess Cybele in Sicily. This presence is mainly attested in rock sanctuaries in the territory of Syracuse, as well as in the Elymian area (perhaps the Elymians themselves had Anatolian origins).

This presentation will present some new evidence of the possibility of a cult dedicated to Cybele in Sicily, which could suggest the existence of contacts between the Near East and Sicily before the Greek colonization.

30. Katarina Petrovićová, “Aeneas the Subversive Hero: the Aeneid as a 19th Century

Founding Epic.”

petrovic@phil.muni.cz Masarykova univerzita / Masaryk University, Czech Republic

Virgil's Aeneid represents perhaps the most famous epic representation of the founding myth in world literature. But this work has one, even more significant, quality. Vergil created a work that historically justified and consolidated the imperial claim of the Roman state. For this reason, too, Vergil's epic soon became a foundational text for generations to come. With its school role, other dimensions were weakened. On the one

hand, it was the most unknown work of antiquity; on the other, it suffered the fate of compulsory literature, becoming the target of various intellectual games and jokes. Parodic versions of the Aeneid appear in European literatures from the 16th century onwards. It is noteworthy, however, that one such Aeneid, Ivan Kotljarevsky's Aeneid of the early 19th century, although its original role was comparable to that of the "upside-down" Aeneids, has returned in a strange detour to the role of a founding work, namely the founding work of Ukrainian national literature. The aim of this paper is to explore in more depth the features that made the parody a founding work of Ukrainian literature and to find possible elements of a new national identity.

31. Carmine Pellegrino, “To be Etruscan in Campania”

cpellegrino@unisa.it (see above under co-author Bellini)

Università degli Studi di Salerno Zoom

32. Aura Piccioni, “For an Archaeology of the Italic peoples in Sicily: Außenseiter,

Migration and Mobility from the Italian Peninsula.”

aura.piccioni@gmail.com

KU Eichstätt-Ingolstadt, Germany, and Università degli Studi di Roma Tor Vergata (Italy) Far from showing a unitarian cultural form, Sicily has always stood out as a cultural melting pot, the result of interactions between indigenous peoples (Elymians, Sicans, Sicilians), Greeks, Phoenicians, later Romans, but also Etruscans and Italics. Quite a few onomastic attestations (cf. the interesting paper of Ampolo 2012, with bibliography) in this sense come from the western part of the island and offer a varied picture, also considering the mythical origins of the indigenous peoples (s., in general, Aristonothos 2012, 209 ff.).

This paper will analyse the archaeological evidence from the 6th-5th century onwards and connect it, based on some examples, such as Monte Iato and Selinunte, to the myth-history of the island, in order to understand the coexistence and conflicts of peoples, but also the interactions of individuals, as the evidence allows us to understand. I will also examine Sicily beyond the indigenous peoples for the Etruscans and Italians as well.

33. Jelena Pilipović, “Aeneadum genetrix. Venus as a symbolic origo gentis Romanae in

Lucretius'; De Rerum Natura, Vergil's Aeneid and Ovid's Ars Amatoria”

abaridovastrela@gmail.com University of Belgrade, Serbia

This contribution explores the idea that these poetic figures have a symbolic and identity value: Aeneadum genetrix is not only the genealogical origin of the Romans, but also the symbolic origin of the Roman collective identity. Imagining the goddess in different ways, the three poets present three different visions of the primordial Roman identity that she embodies, but also send an ideological message. Lucretius'; Venus is the source of fertility, cosmic harmony, beauty of nature and peace in interpersonal relationships (De Rerum Natura 1-46). Inclination towards harmony and peace is thus represented as an essential feature of the gentis Romanae – inherited from Venus as its genealogical and symbolical origo. Just as Romans have a martial identity, acquired from their forefather Mars, through Romulus and Remus, so they also have a Venusian identity. Lucretius thus ideologizes the divine figure of Aphrodite as a cosmic force, inherited from the Homeric Hymn 5 and Empedocles'; poem On Nature (Diogenes Laertius 8.77). The goddess is idealized but also politicized in the Aeneid as well: through her, Vergil seeks to construct a collective identity in which the gens Romana will merge with the gens Iulia. The sublime progenitor of the Julian tribe (Aeneid 1.229-53, etc), Venus embodies not only a personal relationship of motherly love towards Aeneas (1.405-409), but a superpersonal relationship of parental love to the line of descendants that ends with Marcellus. The figure of Venus as the symbolic origo gentis Romanae, created in Ars Amatoria (1.87 etc), is transformed, since the Roman collective identity for Ovid is not ethnic, but urban: instead of a gens Romana, an urbs Roma appears. Through the critique of inspiration, the critique of epiphany, the critique of marriage and war, and the meaninglessness of traditional values breaks through. The goddess is conceived as the embodiment of love enjoyment and thus the core of the Roman identity lies in enjoyment – ironically or not.

34. Beatrice Poletti, “Lavinium, the Most ‘Greek’ of the Latin Cities”

bp72@queensu.ca Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada

Traditionally, Aeneas and other survivors of the Trojan War who fled to Italy to establish a new home for themselves and their posterity founded the city of Lavinium. Numerous sources, from the early analysts to the Augustan historians, relate that Aeneas brought with him his household gods, referred to in the Roman tradition as Penates – the gods of the penus. As descendants of Aeneas, the Romans embraced the cult of his Penates, which became the Penates publici populi Romani. The modes of transfer of these gods to Rome as well as their identity were already matters of debate in antiquity. Cassius Hemina, Varro, Pomponius Atticus, and Dionysius of Halicarnassus thought that they were to be identified with the Great Gods of Samothrace. Others commonly identified them with the Dioscuri, whose cult is also attested in Lavinium as early as the sixth century BCE. Dionysius 1.67 additionally reports the testimony of Timaeus of Tauromenium (ca. mid-4th to early 3 rd century BCE) on the subject. It is an often-overlooked passage, but it might contain important implications for the adoption, in Lavinium, of Greek culture and identity markers. Specifically, Timaeus would have heard from Lavinians that the sacred objects preserved in their sanctuary were bronze and wooden caducei and Trojan earthenware. While Dionysius disputes that such objects could be the Trojan Penates — which he wanted to associate with Greek deities to support his theory that the Romans were also Greek — the description provided by Timaeus offers a fascinating parallel with bronze caducei found in religious contexts in

towns of Magna Graecia and the sanctuary of Olympia. If we credit Timaeus, their presence in Lavinium could be explained in the frame of the contemporary efforts by several Latin cities of strengthening their ties with the Greek world and partaking in a broader, pan-Mediterranean cultural dialogue. This, together with Lavinium’s foundation legend and its original cult of the Trojan Penates, would single out the Latin town as the core of Greek culture in ancient Latium.

35. Lorina Quartarone, “Vergil’s Ulysses: an Oblique Foil for Aeneas”

LNQUARTARONE@stthomas.edu Univ of St Thomas (Minnesota) Zoom

J. D. Reed, Virgil’s Gaze: Nation and Poetry in the Aeneid, argues that Vergil avoids directly identifying the origins of the Romans primarily by opposing them to other national identities. While Vergil traces Aeneas’ lineage to Venus, his deployment of Odysseus as a principal model for Aeneas both in word and action imbues his Trojan hero with a Greek flavor. Conversely, Vergil clearly denigrates Ulysses whenever he directly refers to him in the poem.

The negative portrayal of Ulysses becomes all the more puzzling when considered alongside the early tradition that Italus and Latinus, eponymous heroes of the future Rome, were sons of Circe and Odysseus (Hesiod, Theogony 1011-16). Vergil’s cursory treatment of Circe also marks his rejection of this tradition. That Cicero esteemed Odysseus (e.g., Tusc. Disp. 2.21.48 & 50; 5.16.46, de Orat. 1.44.196) makes Vergil’s disdain all the more surprising. The strong presence of Ulysses in artistic works – from vase paintings to sculpture – attests to his long-standing popularity on the Italian peninsula, even among the imperial family, as the sculptures as Sperlonga suggest.

Following the Homeric epics, Vergil could not avoid modelling Aeneas on Odysseus; but he deliberately distances the pious and trusting Aeneas from the clever (and sometimes distrustful) Odysseus. He both directly presents Odysseus negatively (e.g., Ulixes is durus, 2.7; pellax 2.44; scelerum inventor, 2.164; fandi fictor, 9.602) and dismisses the importance of the helpful Circe – the mother of the Italian race according to the Hesiodic tradition – he also indirectly portrays Aeneas as more sensitive and caring toward his people. For example, Vergil closely models Aeneid 1.184-85 on Odyssey 10.156-71, where either hero, on a solo mission, slays deer: Odysseus downs one stag to feed his crew; Aeneas outdoes him with seven stags. Through such oblique comparisons, Vergil deploys Odysseus as a foil for Aeneas and establishes the unique and beneficent qualities of his heroism. As Vergil rejects the eponymous Italians’ lineage from Odysseus (e.g., Latinus, whom Vergil says descends from Faunus), he distinguishes the proto-Romans from the Greeks, and counters the Hesiodic tradition that links the Italians to the Greeks in ancestry.

36. Antonio Salvati, “La prima guerra romano-sabina come mito di origine”

Università della Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”

info@antoniosalvati.com

(This is the Italian version of the abstract, for English see Santi)

All’inizio, Roma dovette impegnarsi in guerra con i suoi vicini, dopo il Ratto delle Sabine. Romolo ei suoi compagni erano giovani bellicosi e poveri; i Sabini erano anziani ma avevano donne e ogni tipo di ricchezza. Questa guerra si concluse senza vincitori né vinti: Romani e Sabini si unirono e formarono una società completa, provvista di tutto il necessario per vivere. Attraverso la comparazione di questo racconto dell’annalistica con la tradizione norrena della guerra tra Asi e Vani, due gruppi di divinità, G. Dumézil ha proposto un’interpretazione di questi racconti come la rielaborazione di un mito di origine indoeuropeo. Nel nostro intervento, ci proponiamo di comparare di questi racconti dell’annalistica e della mitologia con il mito della guerra di cui il dio giapponese è protagonista per verificare l’estensione di questo mito di origine della società competa.

37. Elena Santagati, “The Origin of Zankle/Messina between Historiography and

Archaeology” co-organizer

elena.santagati@unime.it Università di Messina, Italy

Over the past few decades, archeological studies in ancient Zankle in Sicily have resulted in remarkable discoveries; moreover, in the light of recent archeological excavations in Cuma Opicia and ancient Pithekusa, a thorough analysis of the main literary works is warranted. The integrated analysis of Realia seems to imply that the very first inhabitants of Zankle were Euboeans of Pithekusa, resettling in Cuma and in Zankle itself. Furthermore, an additional revision of trade relations between Ionian and Tyrrhenic settlements – of which Zankle appears to be the strongest counterpart – is needed.

38. Claudia Santi (with Salvati) “The Earliest Roman–Sabine War as an Origin Myth”

Claudia.SANTI@unina2.it Università della Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Italy

At its very beginnings, Rome had to engage in war with its neighbors, after the Rape of the Sabine women. Romulus and his companions were young, warlike and not rich; the Sabines were aged but they had women and every kind of wealth. This war ended with no winners or losers: Romans and Sabines joined together and formed a complete society, provided with everything they needed to live. By comparing the annalistic tale with the Old Norse tradition regarding the conflict between Æsir and Vanir, two groups of deities, G. Dumézil proposed an interpretation of these as the reworking of an Indo-European origin myth. In our presentation, we aim to compare these annalistic and mythical tales with the war myth in which the Japanese god Ōkuninushi plays a role in order to verify the extension of this origin myth. (Yoshida 1963, 293-242).

39. Ben Scolnic, “Karomemphitai: The Karian Role in the Rise of the Saite Dynasty”

rabbi.scolnic@gmail.com Southern Connecticut State University Zoom

“Karomemphitai” is not just the name of an area of Memphis in which Carians from southwestern Anatolia settled in the seventh-sixth centuries BCE. The toponym also reflects the pride of Carians in their role in conquering that famous and sacred city and the recognition and gratitude of their Saite patrons. What better way to create a place for your ethnic group than by becoming an indispensable piece of the political puzzle in a foreign land? To refer to the Carians as “mercenaries” ignores their desire to find a new land in which to create families and homes. The military actions of the Carian soldiers were the first essential step in their acceptance by and assimilation into the Egyptian community. Traditions about oracles from the gods about the role of the Carians can be studied for their etiological importance, for they are foundation stories. A historical reconstruction of the rise of the Saite dynasty in Egypt in the seventh-sixth centuries will by contrast, show the skewed picture of the Carian role in these same events.

40. Nikki Singh

nksingh@colby.edu

Colby College panel chair

41. Gaius Stern, “The Origin of Roman Hatred of Etruscan and Other Kings”

gaius@berkeley.edu gaius@berkeley.edu (Retired)

The Romans held onto several fantastic ideas about their distant past under the monarchy. Livy’s authority has canonized several of these improbable traditions into history (i.e., universally accepted truth). They explain – true or not – why Romans thought or acted the way they did – often by collective instinct. Hence these unrealistic traditions often germinated certain Roman policies, as the origin of Roman hatred of monarchy (i.e., tyranny) at home, and a distrust of monarchy abroad. In a very real sense, these imaginary elements from archaic history made the Romans who they were.

One such claim is that Rome had only seven kings over 243 years, which is clearly impossible. Several of Rome’s kings have been erased from history entirely and all their evil deeds were transferred to the super villain, the possibly-invented Tarquin II Superbus. A related problem is the fall of the monarchy, both how and when. Some scholars have moved the founding of the Republic to a later time, between 500 and 475 BC. A third feature, which I find highly credible, was how often assassination ended one reign and started another. Assassination supposedly took the deaths of Romulus, Titus Tatius, and Tarquin I, and murder claimed several more, including Remus and Servius Tullius. The fact that the next king need not avenge his predecessor (father?) in a non- hereditary system favors this prospect.

How these factors altered Roman political thought will become clear swiftly. Rome decided that monarchy was inherently corrupt and divisive, pitting the monarchy against the Senate whenever a bad ruler took power. The people are missing from this dynamic. But this principle guided Roman thought for centuries and played an obvious role in Roman identity and politics. The accusation of regnum (the thirst for regal power) destroyed not just the Gracchi but also Spurius Cassius, Spurius Maelius, and the Divine Julius. Others also suffered from this predisposition, increasing the need for those with much power to reject or to pretend to reject it as a matter of survival.

42. Kerasia A. Stratiki, “The Origins of the Athenians: Athenian Autochthony: Cecrops

and Erichthonius”

stratiki@yahoo.com Hellenic Open University Zoom

The cult of Greek heroines and heroes owes its origins and its existence over the centuries to the birth and organization of the Greek city as a community organized around well-defined social rules. The heroic cult answers the question of the origins of the polis: the autochthonous heroes, direct descendants of the land of the polis, are those who best personify the rights of citizens over their country, but also the royal origins of the Greek polis, since the first members of the city are also the first kings of this one. The myth and cult of these primordial heroes authenticate the rights of the Greeks over their homeland. The most characteristic example of this idea is that of the partly-snake Cecrops, the first king of Athens and lawgiver, and of Erichthonius, offspring of Hephaestus (likewise lame in some versions or partly a snake in others), the autochthonous heroes of Athens.

43. Stev Talarman, “‘Earthborn’ Indians in Nonnos’ Dionysiaka”

steventaal@gmail.com Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany

In the Dionysiaka of Nonnos of Panopolis, scholars have identified the author’s tendency to designate various actors, particularly foes of Dionysos, as ‘earthborn.’ Taking a small, non-exhaustive selection of the forms in which this epithet appears, one finds e. g. γηγενής (‘earthborn’), πεδοτρεφὲς αἷμα (‘soilbred race’), αὐτόχθων φύτλη (‘race sprung from the land’), and χαμαιγενὴς σταχύς (‘earthborn progeny’). These descriptions are as various and protean as Nonnos’ vast poem itself, in line with the much commented upon aesthetic notion of ποικιλία which is reflected at virtually all levels of the work. Euripides’ portrayal of Pentheus and his father Echion as ‘earthborn’ (Bacc., 538–541) has been identified as an obvious influence in this connexion (to mention merely one aspect of the extensive reception of Euripides’ work to which Nonnos dedicates books 44–46). Dr Anna Leferatou has contextualised Nonnos’ portrayal of the Indians as ‘earthborn reptiles’ (Leferatou 2016, 167) in a syncretic genre of Christian and pagan κατάβασις narration. Another scholar, Dr Fotini Hadjittofi, has identified the episode of ‘earthborn Typhoeus’ at the beginning of the Dionysiaka as the prototypical θεομαχία (viz. against Zeus), and Typhoeus as a prototypical θεομάχος, to whom the enemies of Dionysos are later implicitly or explicitly compared (Hadijittofi 2016, 138). Starting from these and related observations, I will examine several aspects of Nonnos’ portrayal of the Indians as serpentine, earthborn θεομάχοι and place my findings within the context of his literary influences and aims.

44. László Takács co-organizer

Takacs@vtk.ppke.hu

Catholic University of Budapest, Hungary

45. Călin Timoc, “Pojejena - the Genesis of the Roman settlement on the Danube Bank”

calintimoc@gmail.com

The National Museum of Banat, Romania

(see abstract (above) of Cristea)

46. Elisabetta Todisco, “From the Past to the Future. Varro and the Programmatic Value

of the Etymology of Words”

elisabetta.todisco@uniba.it (Italy)

In De Vita Populi Romani and De Gente Populi Romani, Varro reflects upon the past, following Caesar's death. Varro was most concerned with the political significance of the etymological proposal of certain institutional lemmas and the reconstruction of the origin of certain phenomena. For Varro, the origin of words captures the realities that generated them. The recovery of those aspects of the past can offer a model for dealing with the serious crisis, including the institutional one of the middle of the 1st century BC.

In particular, we will focus on the etymology of the institutional words, curia, consul, and censor; in the etymologies/para-etymologies attributed by Varro to these institutional words, we can reflect on the original atmosphere which gave birth to these magistracies. Varro proposes in the period immediately after Caesar’s death a solution to the political and institutional crisis of the time, that is to say a comeback to the original value of these honores, according to his “antiquarian” knowledge.

47. Anna Judit Tóth, “The Bald, the Lame and the Stuttering. Foundation and

Marginality”

tothannajudit@gmail.com National Széchényi Library, Hungary

Continuing my theme from the previous year, I will analyze the scapegoat-like physical attributes of the typical heros-ktistes. A set of bodily deficiencies appears both in myth and ritual that are somehow connected with the idea of foundation, or more generally, with the birth of an extraordinary man. Most of these impairments can be described as a defect in the normal binaries of life and so the loss of human integrity and wholeness: asymmetries of the body (lameness, crookedness), inability for articulated speech (muteness, stuttering), bastardry, baldness. All of them can be manifested as a real, bodily defect, or in a symbolic way: lameness vs. wearing one shoe, hermaphroditism vs. ritual cross-dressing. In this paper I am focusing on the most under- researched issues: stuttering and baldness.

This closed set of motifs can be present in different contexts as the foundation of a city, the birth of a teras-child or a demigod, the expulsion of the scapegoat, the rites of certain festivals. I am arguing that, for the Greeks, marginality, liminality and pollution were overlapping ideas, inasmuch as all implied a separation or even an excommunication from the community.