Yehudah Mirsky: Teacher, Scholar, Mentor

Associate Professor, Near Eastern and Judaic Studies and the Schusterman Center for Israel Studies

January 6, 2017

Since coming to Brandeis in 2012, Prof. Yehudah Mirsky has shared his expertise in Judaism, human rights, the history of Zionist thought, and modern Israel, and distinctive mix of academic and “real world” experience, with the students, faculty and community of the Schusterman Center for Israel Studies at Brandeis University. An increasingly prominent commentator on political, religious, and social issues in Israel and the Jewish world, he is sought out by news sources such as The Atlantic and The New York Times to comment on public events and the underlying trends driving them, and has written for many outlets including The Economist, The New Republic and The American Interest as well as Hebrew journals and newspapers. Recently, The Daily Beast included his work in a listing of the finest journalistic commentary of the post-election season.

At Brandeis, Mirsky not only teaches courses such as “The World to Come: Jewish Messianism from Antiquity to Zionism,” and “Zionism, Israel, and the Crises of Jewish Modernity,” and chairs the Schusterman Scholars Seminar on Israel Studies. He also draws on his unique background to mentor many Orthodox students who are straddling two worlds, one religious and one liberal-arts. Mirsky helps them integrate the disparate currents in their lives while he himself synthesizes his life work – in writing, human rights, law, religion, and scholarship – into his current role as a devoted educator and intellectual.

Drawing on his unique background in both traditional and modern scholarship, government and civil society in Israel, he has become a mentor for students working to integrate different worlds, be they religious, intellectual or political. For Mirsky, the effort to bring together these seemingly disparate fields is very personal. His late father, David Mirsky, professor and administrator at Yeshiva University, was an Orthodox rabbi, a scholar of English literature, a gentle and beloved figure in Jewish communal life – and a sixth-generation Jerusalemite, whose ancestors were prominent 19th century pioneers. This legacy of working to synthesize theory and practice, Judaism and humanism, are central to Mirsky’s work in and out of the classroom.

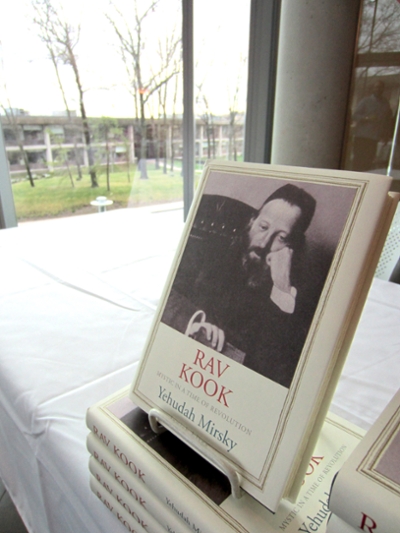

Seminal book on Rav Kook

Last spring, Mirsky won the 2016 Sami Rohr Choice Award of the Jewish Book Council, given to the best non-fiction books of the past two years, for his 2014 volume, Rav Kook: Mystic in a Time of Revolution (Yale University Press), in which he draws on his long-time fascination with a pivotal figure in Jewish, Israeli, and, Mirsky contends, world religious history. Avraham Yitzhak Ha-Cohen Kook (1865-1935), best known as the founder of the Chief Rabbinate in 1921 and the leading thinker of Religious Zionism, was rabbi, jurist, mystic, poet, public figure and philosopher all rolled into one. His stirring, combustible mix of tradition and change, Zionism and universalism resonates deeply – and is still regularly argued over in Israel – as figures on both left and right claim his mantle.

Mirsky’s challenge in writing his Rav Kook monograph was, he says, not only scholarly, but literary too. He sought to create a register of language that would speak to a variety of audiences as he portrayed the life of a passionate mystic and rabbinic figure from the inside out, while also observing him from the outside. This meant sometimes quoting directly, and at other times trying to channel both Rav Kook’s voice, and those of his critics, in an attempt to create a living tapestry.

Mirsky attributes his writing style to his undergraduate English literature major, ruminating that a literary background is helpful in scholarship when “entering imaginatively into the lives of others.” He notes that even his “more scholarly work with lots of footnotes and dependent clauses” tends to have an essayistic feel. He finds himself trying to do interesting things with words, inspired not only by his life-long love of literature, but also by great journalists (George Orwell, Robert Caro, Neil Sheehan, his friend Robert Kaplan), who are dedicated to rigorous thinking and able to produce great work without needing, as academic historians must, to explain in the footnotes why they disagree with others. In Mirsky’s view, they achieve something that historians struggle with: capturing the passion that drives the people they are writing about, something he finds in thinkers who inspire him, like Isaiah Berlin and Leszek Kolakowski.

A native of New York’s Upper West Side (“pregentrification,” he emphasizes) and raised Modern Orthodox, Mirsky was first introduced to Rav Kook at the age of 18 while studying in Yeshivat Har Etzion on the West Bank, before graduating from Yeshiva College in New York in 1982. As a young student in Israel, Mirsky was caught up in Gush Emunim, who were “the spiritual vanguard of the settlement movement,” following their interpretation of Rav Kook’s teachings. Around the same time, he was also introduced to Rav Kook by a very different source, the dean of the yeshiva Rabbi Yehudah Amital, a remarkable figure who eventually founded Israel’s only (and short-lived) religiously-based peace party, Meimad. Mirsky’s work in the decades since, not only his scholarly work but also his work in the US State Department, at think tanks, and as a founder and board member of Ha-Tenuah Ya-Yerushalmit – a movement for a pluralist and livable Jerusalem – have taken him a ways from the settlement movement, even as he is still, as both scholar and activist, deeply engrossed in the world of Religious Zionism.

Working for the greater good

After college, and reeling from his father’s untimely death in 1982, this now-formidable scholar did not think he had what it took to “make it in the field of Jewish studies,” particularly in comparison to the magisterial scholars he was reading, such as Jacob Katz, Gershom Scholem, and Saul Lieberman. Instead of following in his father and grandfather’s footsteps, he chose to go to law school, which he attributes partly to a realization he had as a college student: that the Holocaust might never have happened had Germany had a proper Constitution. At Yale Law School, he was an editor of the law review, and an article he wrote while still a student, on features of the separation of church and state, was cited by the US Supreme Court. According to Mirsky’s account of his legal career, a few months at a law firm “made clear that whatever talents I might have presumably lay elsewhere,” and he struck out in the direction of his passions for writing and public service.

In the late 1980s Mirsky was drawn to Al Gore’s senate campaign due to the fact that Gore was then the standard-bearer of liberal anti-communism, the ideology that sought, in Mirsky’s words, “both to work for freedom at home and abroad and to put government to work enabling citizens to pursue their own lives by their own lights.” He was also working in journalism, for The Economist and now-defunct social democratic journal The New Leader in speech writing, and as a stringer before finding his way to Washington to work as an aide to then-Senators Bob Kerry and eventually Al Gore, with whom he worked on the preparation of his best-selling volume Earth in the Balance: Ecology and the Human Spirit.

After several years at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Mirsky served, from 1994 to 1997, as a political appointee in the Human Rights Bureau of the US State Department under Clinton. He calls this an “extraordinary” experience that taught him what it takes to “move the needle even a little bit” on the issues. Among his roles were bureau spokesperson, speechwriter and staffing special projects (like the Secretary of State’s Advisory Committee on Religious Freedom).

As history unfolds, it all comes back to Judaism

History had a decisive impact on Mirsky’s life at several junctures. Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination in 1995 shook him deeply, eventually inspiring him to redirect his focus from human rights – a universal focus – to Judaism and Israel. He left Washington in 1997 to pursue a mid-career PhD in Religion at Harvard, and to eventually go on Aliyah. He’s written of that experience:

“This was in some ways a quintessentially modern Jewish experience. You are trying to work in a broader societal context to advance universal moral values when something hits you over the head and sends you home, sends you to a place more complex, more obscure, more primal, and more frightening – yet you know that is the place where whatever it is that you are building must begin, and the place where your responsibilities call most urgently, where responsibility points most directly at you.”

A second such juncture came in 2001 with the September 11th attacks, when Mirsky, then living back in New York, served for several months as a volunteer chaplain for the Red Cross, having obtained rabbinic ordination not long before.

Shortly thereafter and in the middle of the Second Intifada, Mirsky made Aliyah and settled in Jerusalem. He was a Fellow at the Van Leer Institute and the Jewish People Policy Institute when he became involved in grass-roots activism in Jerusalem, especially around issues of civic pluralism and fighting gender segregation in public transportation, and was one of the founders of Hatenuah Hayerushalmit, the movement for a pluralist and livable Jerusalem.

He was recruited to Brandeis by Professor Ilan Troen, founding director of the Schusterman Center, and came back to the US along with his family. His wife, Tamar Biala, is a leading figure in Israel’s community of religious feminists. She has twice been a fellow of the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, and has just finished the second volume of her work collecting and editing Midrashim written by contemporary Israeli women (including herself). The couple is now working on an English edition.

Dr. Mirsky is currently working on his more detailed monograph on Rav Kook as well as beginning a new project, one he’s been thinking of since his days in Washington. “I’ve long felt that our basic notions of human rights need some serious rethinking in order to be saved, and that is now, after the last election, clearer than ever before,” he explains. “There are many lenses to be brought to bear on this and the historical experience of Jews and Israel, for good and ill, and the treasures of Jewish thought are very much among them. While being away from Israel is hard, I’m fortunate to be in a setting where my colleagues and especially my students force me day in and out to think harder and as honestly as I can.”

Recently published articles

- "From Every Heresy, Faith, and Holiness from Every Defiled Thing: Towards Rav Kook's Theology of Culture," in Yehuda Sarna, ed. Developing a Jewish Perspective on Culture (New York: KTAV/Yeshiva University Press, 2013), pp. 103-142.

- (With Reuven Ziegler), “Torah and Humanity in a Time of Rebirth: Rabbi Yehuda Amital as Educator and Thinker,” in Torah and Western Thought: Intellectual Portraits of Orthodoxy and Modernity, eds. Meir Y. Soloveichik, Stuart W. Halpern and Shlomo Zuckier (Jerusalem and New York: Maggid Books and the Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought, 2015), pp. 179-217.

- "Revelation and Redemption: Avraham Yitzhak Ha-Cohen Kook, 1865-1935," in J. Picard, et al, eds. Makers of Jewish Modernity (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), pp. 92-107.

A number of Mirsky’s articles, essays and reviews are available online at https://brandeis.academia.edu/YehudahMirsky.

Mirsky is also on Twitter: @YehudahMirsky

Further reading and viewing

"Visions of Israel: Citizenship, Common Cause and Conflict" [Video of Panel at Brookings Institution]

"How Rabin's Murder Changed My Life"