2015-2016 Eizenstat Grantees Blogs

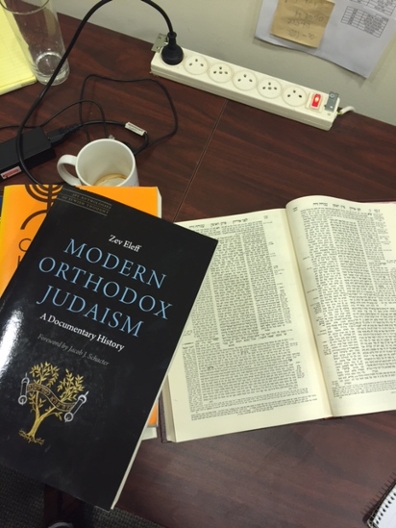

07.13.2016 Jared: "I get to study something very important to my life – Jewish Law"

Jared Kraay Blogpost #2

August 7, 2016

The summer is finally winding down. Over the past few weeks, settling in became working in earnest. After compiling large lists of Rabbinic responsa covering a variety of Jewish legal (halalkhics) confrontations with modernity, Dr. Gordis, Dr. Ellenson, and I began to construct the chapters of the book.

This included three main steps. First, I proposed a selection of responsa, from diverse streams of Judaism, including (but not limited to) Ultra-Orthodoxy, Conservative Judaism, Reconstructionist and Renewal branches of Judaism; and everything in between. Second, we had to select which parts of each responsum, or tshuva in Hebrew, and in some cases this included translations. In this step, we were particularly focused on finding those parts of the responsum where sociological, ethical, or other “extra-legal” considerations explicitly swayed a decisor’s ruling.

These considerations, born not from the text but from the world in which the rabbinic authority lived, shows the paradigmatic attribute of Jewish law which is the malleability and evolution that has happened across movements and throughout millennia. For example, there are some responsa where a rabbinic authority acknowledges that he or she is ruling in contradistinction to either tradition or accepted practice, yet each authority believes in her or his commitment to the advancement of Judaism. Whether or not Jewish law (halakha) is considered statutory or binding according to each authority, the progression of Judaism as a culture, religion, and lifestyle remains paramount in each ruling.

Lastly, we had to ensure that potential readers of this book will understand the core legal issues surrounding each topic. Therefore, I wrote introductions to several of the chapters, outlining which terms and concepts in Jewish liturgy and codes readers should be aware of as they delve into the divergent interpretations of Jewish traditions and texts.

Outside of work, I have been grateful to see many of my friends. Several friends are in the army, and I was lucky enough to catch many of them during their time off or free weekends. Friends from high school are abundant in Jerusalem as well, and we had several impromptu reunions, as well as weekends spent together in Jerusalem, Raanana, and Caesarea.

I also was lucky to join the recent Brandeis University delegation to Al-Quds University.

We traveled to the Palestinian cities of Abu-Dis and Ramallah, meeting with students and professors. While often a difficult and heart-wrenching trip, I ultimately leave hopeful.

Looking forward to sharing more of my experiences back at campus.

Jared

Jared Kraay, Blog post 1: July 13, 2016

Hello from Israel,

I’m lucky that I got back so soon, after being here for a few weeks only some months ago. I arrived smoothly, and despite El Al’s convoluted boarding process from Boston, the journey was quite an easy one. EL AL is of course a great way to acclimatize to Israeli culture, as even on the plane I heard Arabic, Hebrew, English, and Yiddish in the surrounding rows.

After moving into my apartment in Katamon, I scouted out the area for the essentials: a synagogue, a mikvat keilim (ritual bath for immersing utensils), and a supermarket. After spending my first Shabbat in Raanana (just south of Tel Aviv) I began work early Sunday morning. I had been to Shalem College before, but of course I observed it in greater detail when I knew I would be here for an extended period of time. The grounds are nice, and the building is immaculate. Modern glass architecture of the rooms blends with an old, almost “parlor” style of wooden tables, chairs, and antique lamps that surround the common areas. Tucked in the corner of the small library, where students sit on comfortable armchairs and redwood tables, lies my office which bears resemblance to the library around it. My office can get a bit lonely, but thus far I’ve been busy enough not to notice.

The work is rewarding, and I’m learning a lot. I work personally with Dr. Daniel Gordis on a new book he and Dr. David Ellenson hope to publish in the coming few years. The book deals with rabbinic responsa, also known as she’elot v’tshuvot in Hebrew. The topic interests me for several reasons, most importantly because I get to intensively study something very important to my life, Jewish law, or halakha. Additionally, I have been able to acquaintance myself with other ways of looking at the evolving system of Jewish law. In response, unlike other types of Jewish law, one really notices the process that the halakha goes through as it reacts to its environment. As an Orthodox Jew, it has been particularly enlightening to see how Ultra-Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, and Reconstructionist rabbis have used responsa to try and preserve yet advance their respective denominations.

Of course, I’ve made time for seeing my friends, from Brandeis, from high school, and those from my yeshiva (religious seminary). It has been especially lucky to see my friends from yeshiva, considering that almost all of them are currently serving in the IDF and have limited free time. I’m looking forward to another great month here.

Jared

07.03.2016 Camille: "Immerse myself in an Israeli environment and improve my Hebrew"

Camille Brenner’s first blog post: Getting Grounded.

For her special blog site, click here.

JULY 3, 2016

Hey everyone!

I hope you have been enjoying your summers so far! I am now well into my adventure in Israel, so it is about time I share a bit about my experience. Here is what I have been up to:

Somewhere in the middle of a street called Derech Hagefen in Moshav Beit Zayit just outside Jerusalem, there is a little path carved out between the bushes. At around 7:20 a.m. each day, I turn off the street to take this path, pushing through wild plants to arrive at a rugged dirt road. I walk down this road past a cucumber filled greenhouse and a small shaded field of eggplants, zucchini, and fakus (Armenian cucumbers). Just a little bit further and I have arrived at the main porch of Kaima.

Kaima is a sustainable farm that accomplishes the extraordinary task of growing fruits and vegetables in land that is not so easily cultivated. It operates by selling its produce through a Community Supported Agriculture program, a model that is relatively new to Israel. The farm is also unique in that it is run by a motivated staff who work alongside youth that have dropped out of school. It aims to provide an alternative space for these youth to grow and develop on both practical and personal levels. Thanks to the Eizenstat Travel Grant, I have been fortunate enough to spend the last several weeks volunteering here.

My interest in working at Kaima has multiple roots. One of the main ones was to simply to immerse myself in an Israeli environment and to improve my Hebrew. Though I’ve got a long way to go, my Hebrew has already gotten much better and I’m gaining an extremely specific vocabulary. If you are ever wondering how to say “wire,” “wheelbarrow,”or “hydroponic greenhouse” in Hebrew, I may actually be able to help.

The second motivation was what might actually be described as a lack of direction. Since in my third year of college I’d yet to find clarity about my future career, I decided to quit worrying about what might build my resume and do something I was certain I’d enjoy. Kaima’s model intrigued me and seemed to match many of my values surrounding education and social change. Moreover, I was eager to spend the summer outdoors.

So far my time at Kaima has been awesome. On top of the satisfaction of being outside and doing physical work, I’ve been loving all of the people and the overall community that Kaima provides. Each day we sit together and share breakfast and lunch, and relationships have space to flourish throughout the day. As I hoped I would, I am learning a ton from both the staff and teenagers about Israeli culture and society, agriculture, and different ways of contributing to community.

What seems to make Kaima particularly special (and successful) is the level of respect given to each person who comes to work. Every participant is assumed to have something to offer – both in terms of labor and friendship. In my second week, I was invited to join an “erev banot” (girl’s night) to celebrate someone’s birthday. The group contained two teens, two staff members, and myself. We swam in a maayan (spring), ate ice cream, made sushi in a staff member’s yurt (!), and attended a concert – all as equals.

Kaima recognizes the reality that the traditional path is not the only way to contribute to society. So far, one teen has shared with me his dream to open his own farm someday. With another, I discussed the possibility that the discipline and work experience he has gained on the farm are preparing him for his entrance into the army next year. One girl who wakes up at 4:30 a.m. to travel to the farm told me simply that “it’s worth it.” Despite my broken Hebrew, the message has been clear: Kaima is a place of learning and growing in the most authentic sense. The feeling resonates for me as well; I leave the farm each day feeling productive, strong, and at ease.

I am looking forward to the second half of my farm experience and to sharing more about the things I am learning. More updates to come–and hopefully some more pictures!

Best wishes,

Camille L. Brenner

06.27.2016 Austin: "I have the opportunity to uncover a massive building, never before seen by the modern eye"

Austin Shanabrook – Blog post 2: July 28, 2016

Here's the next blog post, with the end of my experiences in Jerusalem and everything that happened at Tel Hazor.

My time spent uncovering the Byzantine palace in the Old City of Jerusalem came to an end about a month ago, after I had spent 6 tireless weeks learning from Moran and the other workers.

Two weeks before I was meant to leave Jerusalem, my supervisor Moran was called to serve with his military unit in the reserves. Although his leaving was unfortunate, it gave me the opportunity to work at another site across from the city of David. This site is far more well known; it is called the Givati Parking Lot.

At Givati, I worked under an archaeologist named Yana Tchekhanovets to uncover a Byzantine era street, which once served to connect the buildings and markets of the outer city with what we now call the Old City. The methodology was far different at this new site, and although I only had two weeks to work, I had the opportunity to learn a new style of excavating, and I met another intelligent archaeologist.

I generally worked on the floor with small tools, using them to slowly, horizontally pick away at the sediment which covered the tiles of the road. In the process of digging, I found pottery shards, bones, and mosaic tiles, all from the surrounding buildings that no longer exist. Because this site was more pure, in that it was not used as an earth-fill, the artifacts I found were of far more interest; they told me about the date of the street, the style of buildings and even the food the people ate. What is perhaps most important is that I was exposed to my first bucket chain, a process in which we throw hundreds of buckets of dirt to each other.

After the conclusion of my eight weeks in Jerusalem, I left for a site in the northern area of the country, not far from Rosh Pina. This site, Tel Hazor, was essentially the birthplace of Israeli archaeology; there I learned from Hebrew University archaeologists Shlomit Bechar, a PhD student and director of the excavations, and Amnon Ben-Tor, a long time archaeologist at Hazor, along with other volunteers from all over the world.

Hazor, though not well known, is everything an archaeologist could want. In ancient history, Hazor was a massive city and trading center, home to native Canaanite cultures for thousands of years. It is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible in the books of Joshua and Judges, which call Hazor the greatest of all the Canaanite kingdoms. Around 1200 BCE, the city was burned to the ground. According to the Book of Joshua, it was Joshua himself who destroyed the city after defeating an alliance of northern kingdoms.

Although the Byzantine era sites were of great interest and enjoyment to me, it is Hazor that captures my interest. I had the opportunity, along with the other volunteers, to excavate what is thought to be the Administrative Palace of the local rulers, in the exact layer that shows the Late Bronze Age destruction, thought to have been carried out by Joshua.

For an archaeologist interested in Bible scholarship, this is fascinating. The discoveries found in this spot could shed light on Joshua's brutal conquests. Firstly, it can clarify the historicity of the biblical accounts. Secondly, it can tell us about how Israelite conquerors dealt with fallen cities. For example, so far no human bones have been found, suggesting at least some parts of the city were abandoned at the time of destruction. Other finds, like pottery, can tell us approximate population estimates, trade ties and wealth of the city, which would give context to the city and Canaanite civilization before the arrival of the Israelites.

Hazor proved to be the best and most interesting of the three sites. Not only because of its relevance to my interests, but because of the team. I found the group, led by our fearless leader Shlomit Bechar, along with the famed archaeologist Amnon Ben-Tor, to be quite family-like. I met people from Canada, South Africa, Spain, Germany and many other places of all different ages. The entire group felt like a community, even if it was only for three weeks and despite its diversity. Both of my roommates for example were Jesuit priests in training.

Sadly, with I leave Israel in just a few days, after I leave Hazor. This summer has been unspeakably fruitful, and I feel more confident that ever in my decision to pursue archaeology. The educational aspect of my time is Israel is paired with the sheer fun I experienced, and I certainly had the best summer of my life.

Hello, my name is Austin Shanabrook, and I'm a rising junior studying archaeological anthropology and NEJS at Brandeis University. As an aspiring archaeologist, one my interests is biblical archaeology, in which I hope to utilize material finds in Israel and biblical analysis to learn more about the world of the Hebrew Bible.

The Eizenstat grant has enabled me to begin gaining experience in Israeli archaeology. My first experience is to spend 8 weeks participating in a dig in the Old City at the Davidson Archaeological Center, right in the shadow of the Al-Asqa mosque. At this site, I work under Israeli archaeologist Moran Hagbi of the Israeli Antiquities Authority and with several other workers to uncover a Byzantine era structure that likely served as a palace of public building.

Even with the later time period, the experience has so far proved invaluable from what I have learned regarding methodology. At this specific site, most of the dirt was what is called an earthfill, essentially a trash site for later civilizations, who dumped useless artifacts into the older structure. We have to dig out the earth and collect enough artifacts to learn about what time periods were deposited there. However, there are unlikely to be significant finds, because all the materials are commonplace vessels that have been purposefully disposed of.

The labor is a lot of digging and hauling dirt to uncover the structure underneath. I often feel the work is a rite of passage for archaeologists, who need to go through the experience of a manual laborer before they can be a leader of their own team.

My work environment is largely made by my coworkers, who are teaching all the necessary skills for such an excavation. My boss, Moran Hagbi, works under the Israeli Antiquities Authority as an archaeologist directing the site. Trained at Bar Ilan University, he has taught me much about his work and has provided invaluable insight into joining the world of archaeology. It certainly does not hurt that his English is better than my Hebrew, by a significant margin.

All the other workers are manual laborers, and all happen to be Arab Israelis who live in East Jerusalem. Although they are not archaeologists, they are experienced in practical methodology, such as how to dig through sediment layer by layer, and have taught me much. What perhaps makes my experience more of a novelty is that they are all between the ages of 45 and 55, but have the care free and fun loving personalities of men far younger than they are. When we are tired and are in need of a break, they often pass the time by throwing pebbles at the others when their backs are turned, untie their shoes or dump water on their unsuspecting heads. I'm happy to say I've joined in their antics, accepting it as part of the experience.

My progress so far can be summarized as follows. I have the opportunity to uncover a massive building never seen by the modern eye, while learning the practical process of archaeological excavations. I am learning about the world of Israeli archaeology, and to be perfectly honest, I am having a fantastic time.

Austin Shannabrook

06.21.2016 Gabriel: "After five months of study in Israel at the Hebrew University."

Gabriel Sanders: June 21, 2016

Back in Denver, Colo. after five months of study in Israel at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, I cannot help but reflect on the experience I have had, the people I have met, and the places and land I have seen. I feel immensely grateful to be safe at home. I feel immensely grateful for the time I had to study in Israel—a dream I have had for years. I am indebted to the Frances Taylor Eizenstat Undergraduate Israel Travel Grant for making it possible.

On Yom HaZikaron, the Memorial Day for Fallen Soldiers and Terror Victims in Israel, as the siren sounded throughout Israel, I could not help but think of all those who were hearing it with me. I could not help but think of all those in Israel, all those in the West Bank and Gaza, who heard the same siren, the same sound. I thought of all those who gave their lives so I—so we—can hear the siren. Those who died so I can be in Israel. Those who have died fighting for Israel. Those who died fighting to get to Israel. And those who died fighting to get to Palestine.

I thought—and think—of the 68 years that have past; the 68 years the country of Israel has been in existence. I think also of the 68 years that have passed since the Palestinians saw their dreams collapse. When Israel came to exist, the Palestinian dream of nationhood ceased and deceased. It is my hope that love can penetrate the hearts and minds of leaders and people in Israel, in the West Bank and Gaza, in the Middle East, and in the world. I wish that hearts and minds will open and look inwards and outwards to uncovering the past and the truth and to discovering each other and themselves and allow all peoples to realize their dreams in harmony.

Being in Israel has given me a greater appreciation and a deeper understanding of the forces contributing to the Israeli psyche and Israeli mentality. I learned in my courses on Palestinian Modern History and Contemporary Israeli Identities the intricacies and complexities surrounding Israeli and Palestinian identity and their self-understanding. I have learned extensively about the development of Israel—the early Zionist thinkers, the pre-mandate and mandate period, Israel’s establishment, the huge waves of immigration from Europe, the Middle East and North Africa in the 1950s, the wars of 1967 and 1973 and their lasting impact, the tumult of the late 1980s and the peace process of the 1990s, the rise of the political party Shas which gave voice to the Sephardi immigrants of the ‘50s, the restarting of negotiations in the early 2000s, and the recent developments that have contributed to the current status between Israel and the Palestinians and the world. I have learned that the way forward is marked with difficulty and is predicated on a need for greater understanding and empathy. It was vital for me to enhance my skills in Hebrew and Arabic, which gave me a greater understanding of Israelis and Palestinians, and on a more personal level, gave me access to speak with professors and people. In my courses I have also strengthened my acumen in economics and in understanding the economic implications affecting Israeli and Palestinian relations.

I had the opportunity to travel Israel—from Eilat in the south to the Golan Heights in the north, and much in between. I spent time in Tiberius and the Galilee, Mitzpe Ramon and Sde Boker, Be’er Sheba, Netanya, Herzliya, and Raanana. As my sister, Tiffany who is a rising senior at the University of Colorado Boulder, was studying at Tel Aviv University (TAU), Tel Aviv became my second home. We would frequent the beautiful beaches of Tel Aviv as often as we could and explore its vibrant and welcoming atmosphere. When we weren’t in Tel Aviv, my sister would travel to Jerusalem, where we would explore the emerging nightlife scene and the historic and religious dimensions of the city. One of the highlights of my trip was connecting with family in Israel.

My father has three siblings who have made aliyah (moved) to Israel. Two live in Jerusalem and one in Raanana. It was an unbelievable joy to get to spend so much time with them (my aunts, uncles, and cousins), celebrating Shabbat and holidays and coming together for special family occasions. We went to student day concerts in Jerusalem (Hebrew University), Tel Aviv (TAU), and Be’er Sheba (Ben Gurion University), where one of my cousin’s studies. On my mother’s side we have relatives who moved to Israel (then Palestine) in the 1930s to start a moshav, a community like a kibbutz that is more privatized, just outside of Netanya. My sister and I spent a lovely weekend there and learned about our family history, the history of the moshav and Israel. During our last week in Israel, we had the pleasure of a visit from our father, stepmother, and half-sisters—it was our stepmother and half-sisters first time in Israel. Celebrating the holiday of Shavuot, a harvest festival that marks the completion of Sefirat Ha’Omer (the counting of 50 days leading up to the holiday) and the Jews’ receiving of the Torah on Mount Sinai, with them and our family was a great way to bring our experience to its conclusion.

Five days before my departure from Israel, an attack was perpetrated at the Sorona Market in Tel Aviv, an upscale, lively outdoor—and indoor—marketplace. The night before the attack I was at the Sorona Market— for dinner with my sister and brother at the same time terrorists attacked restaurant goers the following night. (My twin sister, Tiffany, studied at Tel Aviv University this semester, and my brother, Benjamin, joined us in Israel after leading a Taglit Birthright trip for the University of Colorado Boulder.) It is chilling to envisage how our time in Israel could have ended had we been there the following night or had the attack been carried out the night before. We are lucky. In the world of today, many are not. The attack in Orlando as well as the attack in Tel Aviv (and attacks of this sort) are somber and stark reminders of the preciousness of life.

It makes one appreciative of life and emboldened to continue to live fully and unencumbered. This was the way I lived in Israel this semester. Though surrounded—in Jerusalem—by tensions and at times toxicity, I chose to be alert, but also aware of the joy, love and spirit that make up the Israel I know and love.

In the words of one of Israel’s great writers, Amos Oz, “Both sides know compromise is essential. They don’t love each other. They cheat on each other. They shout at each other. But whether they like it or not, they see each other.” In recognizing the mutual blindness that has occurred and seeing each other face-to-face, the hope is that forward movement can begin.

Thank you to the Frances Taylor Eizenstat Undergraduate Israel Travel Grant and to the Schusterman Center for Israel Studies at Brandeis University for inspiring students at Brandeis to pursue study in Israel and for making my study in Israel possible. I am most grateful.

Gabriel Sanders ‘17

Gabriel Sanders: June 10, 2016

My academic semester is underway at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where I am spending a semester abroad pursuing my degrees in Economics and Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies. I am extremely privileged to live in Jerusalem and study at a university, much like Brandeis, that prides itself on academic rigor and academic exploration.

Being in Israel allows for a fuller and deeper picture to come into focus as to the many facets and pieces that play into the Israeli and Palestinian puzzle. In Jerusalem, two peoples, two nations, two societies are presented with the opportunity for coexistence. The Hebrew University borders the West Bank, while still remaining in the confines of the Israeli state; the university itself sits, physically, and in terms of its rich student body of Jews, Christians, Muslims, and a wide array of others, in both camps. Longstanding ideological and historical conflict have prevented, and at times stymied the prospect of peace and prosperity. Yet that dream—of peaceful coexistence, of self-determination for two nations—is still very much alive today. For it to ever exist in true confluence, Jerusalem, the sacrosanct locus of Israel and Palestine and the home to the religious triumvirate of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, must serve as an integral part of this amalgamation. Yet, can these aspirations, at many times—historically and currently—competing, find a way to converge?

My semester began with a month-long intensive Hebrew language course called Ulpan. Ulpan aims to help students acclimate to Israeli society and gain necessary speaking capabilities to communicate while in Israel. I am also pursuing study of Arabic. It is critical, for my personal and professional goals, to learn Hebrew and Arabic. Both languages and cultures have rich and complex histories. By showing an appreciation and seriousness to learn another language, one takes the first of many steps in reaching a state of compassion and attaining greater understanding of the larger picture and whole story. Once people are able to understand what the other is truly trying to say, greater comprehension can occur, leading to a realization of shared commonalities and goals.

My coursework for this semester abroad at the Hebrew University is split between Economics (Game Theory and Neuroeconomics) and Middle Eastern Studies: (The Palestinians: Modern History and Society and From Pioneer and Sabra to Contemporary Israeli Identities). It is a truly special opportunity to study alongside students from around the world and learn from excellent professors, who have thoughtful and deep understandings of the issues in Israeli and Palestinian society and in their areas of expertise.

At The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, students—Jewish, Muslim and Christian—live and study together. On a given Wednesday or Thursday night at the Einstein campus bar, one can see all these students interacting and sharing conversation over beer or a cocktail. Food and drink have a way of bringing people together. At French Hill Falafel, arguably the best falafel in Jerusalem, student life is the topic of conversation and preconceived notions are abandoned, or at least put on hold, while students and professors, locals and foreigners, Israelis and Palestinians, share what is common rather than what divides people. It is here, in Jerusalem, that greater integration and the realization of two aspiring nations can come to fruition. There are many models in Israel that should be internalized and exemplified. Haifa, a historic seaport town located to the northern rim of Israel, boasts a vibrant and robust Palestinian community; an intersection of Israeli and Palestinian life. Tel Aviv, a city where secularism converges—and at times conflicts—with the religious dimensions of Israel, is host to pockets of Israeli and Palestinian integration.

However, tensions still exist.

Attacks continue to be perpetrated by Palestinians targeting Israelis. Israel continues to occupy areas in which Palestinians live. Many Palestinians are fed up with their inferior position; many are disenchanted, frustrated, disappointed, and plainly, unhappy. They have a right to feel this way.

They cannot live this way forever. Israel cannot live this way forever. Something must be done.

Through the Frances Taylor Eizenstat Undergraduate Israel Travel Grant, I have been able to gain a better appreciation and understanding of the stories of the Israelis and Palestinians; to explore their histories, areas of contention, and possibilities for peaceful coexistence. I am most thankful to have been given this opportunity.

Gabriel Sanders

Brandeis University ‘17

01.18.2016 Sophie: "Research excites me because of the potential it has to shape our knowledge about how to help people get through their experiences of trauma."

In more ways than one, my winter at the trauma center is now characterized by fire. In my last week in Jerusalem, there was a fire on the floor below us in the offices of B’Tselem, a non-profit that receives a lot of political attention. Luckily no one was injured, but there was a fair amount of damage to the building, leaving our offices inaccessible. The response by the center’s leadership, in my mind, exemplified what I love so much about Israel: our director invited everyone to his house Monday morning and while we ate breakfast together, a plan was made to use other spaces throughout the city for therapy rooms and group programs, and business went on as usual.

In addition to continuing to work on the international course, I was involved in multiple research projects, some of which I will continue working on from afar. I always thought I wanted to work with people in a clinical setting, which I still enjoy, but my work at the center has helped me discover how much I love research. I worked on a literature review about building resilience in children through attention-training, a completely new topic for me, as well as a literature review of the use of EEG in differential diagnosis of PTSD and related anxiety disorders and a subsequent recommendation for the use of EEG in the center’s interventions. I also had experiences at the opposite end of the research process revising and preparing articles for publication, a very valuable experience for a young researcher.

Research excites me because of the potential it has to shape our knowledge about how to help people get through their experiences of trauma. In the excitement of the “detective” work involved; of the technicalities of measurements, definitions, methodology, etc., I think it is possible to lose a small bit of sight of the essence of trauma. Especially for this reason, I’m grateful that I’m exposed to both research and real stories through my work at the trauma center. During a Saturday meal I spent with one of the leader’s of the center, we talked about an incredibly difficult case of domestic violence and abuse, which most staff members were aware of due to the truly heinous nature of the trauma. It was a special experience in itself to hear active case studies from such an established professional. I wanted to learn more about some treatment techniques (EMDR, for example). In experiencing these techniques in a training setting, I was struck by the amazing ability that the clinicians at the center have to listen to and work with deeply traumatic material. Today, I sat in my Waltham apartment, reading about the brutal murder of Israeli nurse Dafna Meir, killed in her home defending her six children from a knife-wielding terrorist. I was deeply pained by the story, but I also found myself thinking, “what kind of help does her family need? what kind of programs could really help her kids?” Working at the trauma center has left me with a bittersweet hope – a combination of the understanding that seemingly unimaginable traumas will happen, along with the belief that in every trauma there is also the potential for growth and coping.

Despite the “big” lessons I’ve learned at the center, my most treasured memories are the “little” moments. I spent one of my last days at Hebrew University, with the professor I work most closely with, writing a research proposal for a new project to eventually develop and pilot an intervention to shield youth from radicalization through individual, family and community resilience building. We liked the timeless phrase, “what fires together wires together”, and had spent a good few hours re-wording the explanation in our proposal of the connection between biology and behavior. Per usual, we didn’t have as much time as we needed, but were determined to finish what we had started, so I typed furiously on my laptop in the back seat of her car as we flew first through Jerusalem’s rush hour traffic and then down the remote hills of a Moshav (village) on our way to a center staff goodbye party. It’s these moments that are the most memorable. We laughed at ourselves, but at the end of the night, as we sadly said goodbyes, she made the beautiful connection, returning to the idea of fire, that the sentence we worked so hard on could also be applied to our work together. “What fires together wires together”; I’ve never felt as stimulated as I have during my work at the trauma center, surrounded by such intelligent and passionate mentors, and our mutual excitement and teamwork results in incredibly strong connections.

At the end of my first experience at the center, my supervisor gave me a pair of sandals I had been admiring all summer, with the following note: “In Israel, we have a saying that it’s not wise to give a person a pair of shoes, because they’re sure to walk away in them. That said, we know it’s your time to go, so we hope you leave us feeling enriched and confident. We also hope that the path you take might someday bring you back to us.” I’m incredibly thankful that my continued personal and professional journey did bring me back to the center, and as sad as I am to have left Jerusalem, I’m excited to use what I’ve learned this winter as I continue to learn and grow.

Sophie Brickman

01.01.2016

My passion for the field of trauma psychology developed when my academic interest in psychology began to merge with my personal experiences in Israel. Although I had spent much prior time in Israel, the summer of 2014 piqued my interest in trauma psychology. Operation Protective Edge was just beginning and my journey home to Israel was already tense as I flew from South Africa to Turkey to Israel on one of the last flights from Istanbul before the Turkish government started banning flights to Tel Aviv. While I was staying in the South during my first week, I heard 18 rocket sirens: In the middle of the night, at the mall… Once, while we were driving through Herzliya, we didn’t see a nearby shelter, so we stood against a brick building and watched as the Iron Dome intercepted a rocket above. I moved to Jerusalem a week later, where threats changed but tension remained. I watched, once, as a terrorist drove a bulldozer into one of the cars of the light-rail (metro) behind mine. I left the old city when flare-based explosions set off in neighboring villages were too overwhelming. We were told not to walk on our own due to the attempted kidnappings, not to take the light rail, as it was the target of much violence, and not to take cabs since decoys were being used in kidnappings. Yet, life went on. I spent inspiring days learning in the Old City; everyone went to work, to restaurants, to the grocery store. I had the unique perspective of experiencing this reality as both an insider and an outsider, and while this was not my first exposure to the tensions of life in Israel, I was fascinated. I wanted to learn everything about the strength and resilience I saw daily.

This desire led me to an incredible organization, the Israel Center for the Treatment of Psychotrauma (ICTP). I began my work at the center in the summer of 2015 as a teaching assistant for their international course, “Trauma and Resilience: Theory and Practice from the Israeli Experience”. It was a valuable experience to bring students and professionals from 14 different countries to Jerusalem to learn and teach collectively. I also became involved with an additional research project focused on developing an intensive PTSD treatment program. It was a great introduction to the field, and I knew I wanted to continue my involvement. Returning to the trauma center for the winter break is allowing me to continue the work I began with more experience and focus. I’m working on coordinating the course for next summer and am participating in research projects focused on self-regulation, resilience interventions, and post-traumatic growth. I spend most of my time at the trauma center, and some days at Hebrew University working on our research project. Each experience provides a new opportunity to turn what I’ve learned about from my courses, into practice. I love research because it allows us explore potential answers to pressing questions, but I’ve recently gained both a new appreciation for and perspective on the research process. I received a crash course in structural equation modeling, perhaps the most tedious and precise part of a research project, which exemplified the important relationship between theory and evidence in research across disciplines. I’m working most intensely on a proposal for a new project that would be implemented in tiers of information gathering, intervention design, and assessment. Such a long-term project helps connect research to clinical interventions and emphasizes the importance of first asking both “what do we already know” and “what do we need to find out” before attempting to propose any plan for intervention.

Through the international course, I’ve learned about the concept of a shared traumatic reality, which characterizes situations in which the helper/professional is exposed to the same communal trauma as the people being helped/treated. Unfortunately, this is common here. It makes the work that ICTP does so inspiring. The “Wave of Terror” that began in September of this year has included approximately 88 stabbings, 9shootings, and 14 car-rammings, yet here I am sitting with a team of professionals committed to exploring risk and protective factors for the development of post-traumatic stress and risk-taking behaviors, designing interventions for grieving families, soldiers, children growing up “under fire”, and understanding the idea of post-traumatic growth.

Yesterday, I walked with a friend into the Old City through the same gate where two Rabbis were killed in terror stabbing just a few days ago. We talked for almost an hour with a Bedouin jeweler in the Christian quarter market about his family history, culture, artwork and education. I practiced my Arabic. It was a beautiful interaction, and as I left the Old City, I was reminded of something a friend said about visiting Israel: “This is not a dress rehearsal.” It’s easy, even natural, to feel afraid, to stop reading the news, to look for distractions and ways to forget about a high-stress environment, or to forget that all over the globe we are at times surrounded by trauma. However, it is 100% true that this is not a dress rehearsal; it is a reality. My experiences in Israel and at the trauma center continue to teach me the importance of facing this reality head on. This way, we can help turn fear into motivation, understanding and help for others.

Sophie Brickman