The Changing Identity of Jews in the American West

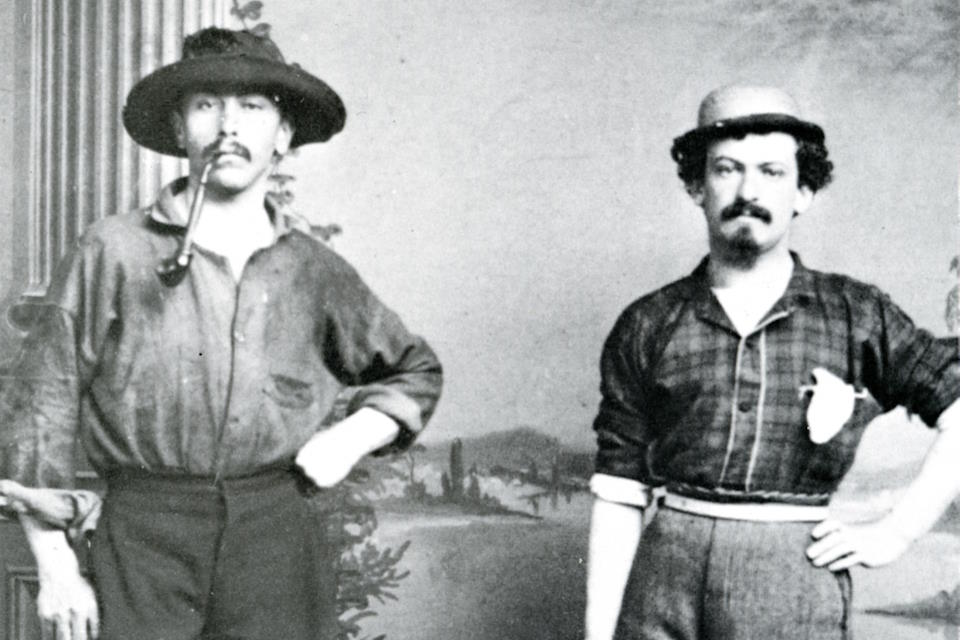

German Jewish immigrant Seligmann Heilner, left, and a friend in the mid-1800s. Heilner went west during the California Gold Rush but eventually wound up starting a store in Sparta, Oregon, selling goods and supplies to miners.

Photo Credit: Courtesy: Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education

May 22, 2023

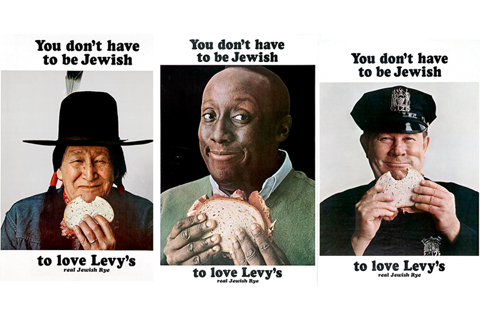

There were certainly gunslingers, cowboys, cattle rustlers, and prospectors among the Jews who settled the 19th-century American West, but most plied the same trade as Jews had since the Middle Ages — they were merchants and peddlers.

These early settlers moved West to sell everything from tents, tools, food, household goods, and, of course, shmatas (Yiddish for clothing) and soon prospered. Most famous among them was Levi Strauss, who built his San Francisco dry goods store into a blue jeans empire, but there were others all across the region.

A new book published by Brandeis University Press, "Jewish Identities in the American West," charts how migration and settlement in the Pacific West transformed the way these Jews saw themselves and viewed and interacted with Blacks, Native Americans, Latinxs, Asians, and other groups.

Edited by historian Ellen Eisenberg, the volume contains nine scholarly essays on such topics as 19th-century Jewish pioneers in Oregon, Jewish communists in 1920s Los Angeles, and the complicated attitude of Jews toward affirmative action and desegregation.

Through most of the 1800s, Jews did not encounter antisemitism out West. But this advantage had a dark side: They could participate fully in the racism and colonization perpetrated by white settlers.

But by the 1920s, with America in thrall to an anti-immigrant backlash, Jews began to feel like outsiders — "not-quite whites" or "off-whites" is how the book describes their new status. In turn, Jews rethought their relationship with other marginalized groups.

TJE spoke about the book with Eisenberg, the Dwight and Margaret Lear Professor of American History at Willamette University in Oregon.

When did Jews start moving West, and why?

They started moving at the same time as other Americans, in the 1850s. There was a big influx in the wake of the California Gold Rush. This first wave was largely Jews of Germanic origin. They were seeking economic opportunities and freedoms they didn't have in Europe.

Where did they settle, and what did they do?

The majority settled in towns, very often small and isolated. These communities sprang up, and the Jews arrived to serve their needs. Jews were supplying all sorts of goods in short supply in remote parts of the West, whether it was mining supplies, seeds for farming, or general merchandise and retail household goods.

They did this by setting up regional supply networks. There might have been a brother in New York, another in San Francisco, and then sons-in-law, cousins, and nephews who fanned out to smaller communities and sold their wares.

Were these Jews fully accepted into their communities?

Yes. What was different for Jews out West was that they were getting in on the ground floor. They weren't entering an already established society, like Boston. There was no existing social hierarchy.

If you look at Jewish participation in local organizations like chambers of commerce, they were often founding members. They also served on town councils or school boards.

In many western states, there were "native sons" and "pioneer" groups. These groups were for those who could trace their lineage to before the territory became a state and were fairly exclusive. In some cases, Jews served as presidents and elected officers.

To what extent did Jews participate in driving Native Americans from their lands?

Our understanding and view of this have really changed in the last few years. It used to be, "Oh, wow, Jews were pioneers? Isn't that amazing!" Now, it's "Jews were pioneers. They participated in settler colonialism."

So, it wasn't just that Jews were in the chambers of commerce. They were also in or supported the militias. They fought against Native Americans and, at times, participated in genocide.

And while it's true that few Jews were homesteaders [settlers who claimed land under the Homestead Act of 1862], they helped open up the area for further settlement. It was their commerce and provision of supplies that enabled people to settle in these remote areas.

Although Jews were a small minority in the West and certainly not the instigators of the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, they did play a role in the colonization process that pushed Native Americans off the land.

What changes took place in the 20th century?

This was when you saw antisemitism rise in this country. There were exclusive country clubs and law firms that previously welcomed Jews but now wouldn't hire them.

There was also segregation.

In the mid-to late-19th century there was no such thing as a Jewish neighborhood. There was a lot of mixing with the general population. But as the 20th century got underway, and with the arrival of a new wave of Eastern European and Sephardic Jews, they started creating and living in predominantly Jewish neighborhoods and communities.

How did this change how Jews saw themselves?

Earlier arrivals had considered themselves, and largely been treated, as part of white society, but now, Jews started to think of themselves as a minority. In general, there was much more of a sense of otherness.

Which changes the way Jews related to other marginalized groups.

Yes, we see Jews relating to other groups experiencing discrimination and racism.

It was facilitated by the fact that many of the communities where Jews were living were mixed neighborhoods. If you take, for example, what was then called the central district of Seattle or Boyle Heights in Los Angeles, those neighborhoods were not exclusively Jewish. They were neighborhoods with a high Jewish population, but there were also substantial numbers of Mexican, Japanese American, or other groups.

There was this mixture of all sorts of folks. The kids all went to school together. So there's much more of a connection with these other marginalized groups.

One example of Jews aligning with other minority groups is the L.A. Young Communist League. In the book, UCLA historian Caroline Luce writes about how the Jews in the league initially wanted little to do with their Judaism, but that soon changed.

Many members of the Communist League grew up in lefty Jewish families of Eastern European descent. They were involved in the communist movement in Los Angeles in the 1920s and '30s by organizing farm and factory workers, Mexicans, Italians, the Irish, and other groups.

They wanted to identify as internationalists. They separated themselves from their Jewish identity. A number of them even changed their names.

Luce recounts one incident where a mob beat up several young communists. The newspapers described several victims as having very ethnic kind of traits, as "dark and sultry." They used words that linked them to Jewishness. Inevitably, this kind of antisemitism, whether it was from the public, government, media, or other forces, connected the communists back to their Judaism again.

Then as in the 1930s, with the rise of Nazism and antisemitism in Europe, some re-embraced their Jewish identity.

How did Jews in the West respond to the civil rights movement?

There's no question that Jews were more supportive of civil rights than the white population as a whole. But the situation was also complicated and nuanced.

Sara Smith '09, MAT '10, a Jewish educator in Los Angeles, writes about the history of public school busing in the 1970s. Officially, many L.A. Jewish leaders advocated for busing because they supported desegregation and civil rights.But the reality was that many Jewish parents didn't want their kids to be bused. And this led to the opening of many Jewish day schools in the area. Rabbis were on record saying they supported busing but also saying they'd long had this dream of opening a Jewish day school to ensure continuity among the Jewish people.

It was a conflicted moment for Jews where what they said publicly didn’t necessarily conform to how they behaved.

Max Modiano Daniel, a Jewish educator in Northern California, writes about Sephardic Jews out West in the post-World War II period. How did they make sense of their Jewish identity?

It really depended.

Daniel discusses the case of Marco DeFunis Jr., a Sephardic Jew in Seattle, who was rejected from law school at the University of Washington in 1971. He said he was rejected because he was white. He didn't claim his Sephardic status as a minority status.

But then, in Los Angeles, Sephardic Jews applied for the public school system's program to diversify the teaching staff. They said they were eligible for the program because they were Hispanic.

But in 1978, the school district issued a memo saying, "Sephardic Jews are white."

Many Jews are now wrestling with how responsible they should feel for the sins of America's past. Looking at Jews out West, how do you assess that?

I don't think there's an easy answer. If we're looking at the Pioneer age, I don't see much difference between Jewish attitudes and those of other whites toward marginalized groups.

But that was not so true in the mid-to late-20th century, where there's no question Jews supported civil rights.

I think it's a really important conversation to have, though, because many of us now have the advantages and privileges of whiteness. On the other hand, Jews of color are a growing demographic.

When we speak about Jews today, it starts to get very complicated.