The Literary Equivalent of Eavesdropping

Nov. 13, 2017

By Violet Fearon

Editor's note: This is one of an occasional profile of the expanding Jewish-Feminist collections at The Archives & Special Collections at the Brandeis Goldfarb Library.

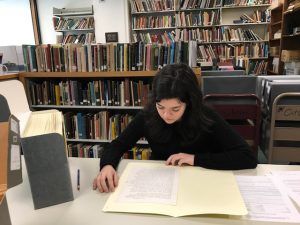

Before I gain access to the carefully stored correspondence of Esther M. Broner, I'm given a few instructions: no pen, keep the documents flat on the table at all times, file everything back exactly in the order you found it. In this quiet room, filled with books and cardboard boxes, it feels a little like I'm about to undertake some kind of secret mission. The first letter I examine is dated from the early 60s; it feels brittle and thin. Even if I hadn't been briefed on proper handling procedure, there's something about old paper that tells you to treat it with care.

As I place the designated cardboard marker in the box to hold the document's place, two women across the room are having an intense whispered conversation. Their low voices mean it is something I am not supposed to hear; a private conversation. At the back of my brain — and I don’t think I'm alone in this — is a curiosity. We all want to be privy to things not meant for us.

As I place the designated cardboard marker in the box to hold the document's place, two women across the room are having an intense whispered conversation. Their low voices mean it is something I am not supposed to hear; a private conversation. At the back of my brain — and I don’t think I'm alone in this — is a curiosity. We all want to be privy to things not meant for us.

Maybe that's why I was excited to come here. Reading correspondence is, after all, the literary equivalent of eavesdropping. There's a sense that you're being a little sneaky — a little bit of a busybody. And, if I'm honest with myself, that's where most of the fun of the whole endeavor comes from. You are reading something not meant for your eyes, something intended to be kept to the confines of friends and family. All of a sudden, the famous figures I remember reading about who instructed their diaries and letters to be burnt upon their deaths suddenly seemed like very forward-thinking individuals.

First, a little backstory. Esther M. Broner was a Jewish American author, whose works focused on fusing her feminism with her faith. She wrote 10 books, among them renowned works like "A Weave of Women and The Women's Haggadah," which largely revolved around themes of creating new, women-centric Jewish rituals forging a feminist identity within the confines of religion and tradition. In 1976, she held the first all-female Passover seder on the floor of her NYC apartment, surrounded by a horde of plants, with women such as Letty Cottin Pogrebin and Gloria Steinem (the founders of Ms. Magazine) in attendance.

In her correspondence, some of what I found was expected: evidence of a woman with an intense focus on Judaism and feminism (or, in her own words in a letter to a friend, "my Jewish thing"). But I also found something else — something that makes correspondence uniquely valuable to researchers: a human being. There is joy when babies are born, and sadness when relatives die. She commiserates with friends over the incompetency of various politicians. During a visit to London, there’s musings on her love for the picturesque gardens, though some cultural frustrations that still ring true today ("The British are quite relaxed, and to the impatient American it can be somewhat exasperating — it's always "Would you have another cup of tea," when you’re trying to get a steady stream of work done.").

A letter from a friend, Susan, who tells Broner to never forget to be cheeky, because "sass is so fine." A note from a writing mentor, Professor Edward Albee, to "Work hard — you are so good." Albee also talks about the process of writing his latest play; he hasn't settled on a title yet, but he likes the sound of "Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?"

When we study an author's works, it's easy to see them as static creations — things that were always there, or that were summoned into creation in some frenzy of creativity. In reality, of course, writing is a long and gradual process, no matter who's doing it. There’s no clearer way to find this out than by reading personal, casual writings. In a 1976 journal entry, Broner described the beginnings of the themes that would come to define her work, writing, "Michele and I talk about magic and the idea for my book becomes clearer — a ritual between women, holidays and rituals — births to deaths — and the weave of women who enact these occasions and what happens to them, Israelis and Americans — here and there — who live together and who returns, who dies by fire and who by hunger... I don't like the idea of women and black magic — but women and ritual — and ritual deep in our roots and cultural origins, can organize the book."

Working your way through years of a person's life in the space of a few hours can be a strange experience. In the course of a few pages, her daughter, Nahama, has transformed from a little girl in the 1960s trying on trenchcoats and deciding to get her hair cut into "the most adorable bangs”" to a 1970s teenager who "laughed nastily" at her father's recounting of Esther and his honeymoon, prompting Esther to write a long passage on how difficult teenagers are.

(In the spirit of research, later I googled "Nahama Broner," hoping to find some old family photographs so I could put faces to story. Instead, I found her RateMyProfessor page, with a stream of NYU undergraduates reviewing her skills in teaching psychology. She seems to be a very good professor, though now bereft of bangs).

In a way, it was much more — "disturbing" is too dramatic, but perhaps "perturbing”" is the right word — than I expected, paging through decades of a life in a single afternoon. Years slip through your fingers; there is joy, then sadness, then anger, then joy again. In one of the earliest documents, Broner discusses an uncle who had just passed away; she muses over his life, wonders if he spent more time happy or sad. In closing, she writes: "And his death is painful because he had not realized all of his dreams. But then, who does?"

Violet Fearon, a freshman and Humanities Fellow, s the HBI student blogger.

Violet Fearon, a freshman and Humanities Fellow, s the HBI student blogger.

To learn more about the Jewish-Feminist collections or to make an appointment, email Chloe Morse-Harding, Reference and Instruction Archivist, or call 781-736-4657.