Reclaiming a More Inclusive Yiddish

Aug. 5, 2021

By Alec Weiker

Editor’s note: The HBI Research Award program awards grants annually to support research or artistic projects in Jewish women’s and gender studies across a range of disciplines. In 2021, HBI gave out 16 awards totaling $62,000. This is one in an occasional series on past research award recipients and their ongoing work.

What if we are missing whole aspects of Yiddish-Jewish life because we are not looking in the right place? What if the exclusion of certain Yiddish-Jewish narratives served to exclude those who may have been there all along?

What if we are missing whole aspects of Yiddish-Jewish life because we are not looking in the right place? What if the exclusion of certain Yiddish-Jewish narratives served to exclude those who may have been there all along?

These are some of the questions that Zohar Weiman-Kelman (who goes by they/them and she/her pronouns) is asking. They are part of a group of academics challenging the way that Yiddish is characterized and studied in the modern Jewish world. HBI granted Weiman-Kelman a 2021 Research Award to complete research focusing on both the published and unpublished work of Yiddish poet Celia Dropkin. They plan to analyze this work through a combination of different methods including poetic analysis, philology, and sexology. This methodology hopes to serve as a path to "understand[ing] what happens to us as readers when we read [her poetry] and what it meant to use that erotic imagery in the time of writing."

Weiman-Kelman notes that Yiddish, often is either treated with contempt or relegated to a specific cultural role associated with nostalgia, humor or the family. These narrow and heteronormative confines of Yiddish fail to take into account the dynamic nature of Yiddish language and culture in 20th century America. Yiddish was not only a facet of early Jewish family life, but played an important role in the political, cultural and sexual lives of Jewish Americans. Thus this conception of Yiddish does more to "erase rather than to reveal," they said.

"We're covering especially radical histories, political histories and queer histories. It is a really important way of adding nuance to historical accounts and then also adding nuance to present politics," they said.One aspect that common discourse about Yiddish forgets is the interesting and meaningful aspects of Yiddish culture on the margins of society. "The narrowing of Yiddish also stood in or created a narrowing of what being Jewish was in America," they said. One place to start expanding the interesting and meaningful aspects of Yiddish culture is with Dropkin.

A Yiddish poet from early 20th-century America, Dropkin published only one book of poems in her lifetime: "In Heysn Vint (In the Hot Wind)." Included are poems that transgress normative sexuality, poems that express anger and passion, and poems that embody unmitigated sexuality and eroticism. Despite Dropkin's work representing a rich trove for those studying Yiddish culture, the Jewish world has long been hesitant to engage with her work and the realities of Yiddish sexuality. Much of Dropkin's other unpublished work remains unstudied. Zohar Weiman-Kelman is striving to change that.

A Yiddish poet from early 20th-century America, Dropkin published only one book of poems in her lifetime: "In Heysn Vint (In the Hot Wind)." Included are poems that transgress normative sexuality, poems that express anger and passion, and poems that embody unmitigated sexuality and eroticism. Despite Dropkin's work representing a rich trove for those studying Yiddish culture, the Jewish world has long been hesitant to engage with her work and the realities of Yiddish sexuality. Much of Dropkin's other unpublished work remains unstudied. Zohar Weiman-Kelman is striving to change that.

This research on Dropkin is part of a larger book-project tentatively titled "(Un)Archiving Yiddish Sex." They are focusing not only on taking pieces out of different archives of Yiddish history, but working to create a broader archive of Yiddish sexuality. "I think of [this] as an archive at the connection of body, language and history," they said. In this way, Weiman-Kelman hopes to explore the body of Yiddish culture that has been forgotten, yet can be incredibly significant for modern Jewish readers, especially Jewish outsiders.

They note that studying and analyzing queer history and deviant sexualities becomes an important project not just for queer people, but for Jews as a whole largely due to Jews' unique historical circumstances in America. For Jews, the issue of Jewish continuity remains an everlasting question: how do we perpetuate Jewish existence? While for some the answer is simple, Weiman-Kelman has spoken about how the study of Yiddish can present an alternative model of continuity especially for queer Jews for whom biological reproduction is not an option. When we study and pass on pieces of Yiddish and Jewish culture, like that of Dropkin, we drive the process of cultural transmission, achieving a powerful and queer form of Jewish continuity.

Another important function of this project is that it illuminates the fact that Jewish sexual outsiders have been around all along, but their legacies were left behind. Studying queer and deviant culture in Yiddish can allow for those in the Jewish community to see themselves in the Jewish past and therefore the Jewish present. "It's less the case now, but for a good number of years, mainstream institution Judaism was not un-homophobic and even very inhospitable to even people still alive," Weiman-Kelman said. The realities of queer and Jewish sexuality serves as an important tool towards reclaiming that past.

Dropkin's transgressive poetry fits into this larger project. Weiman-Kelman notes that Dropkin came to their attention due to the incredibly powerful erotic voice that she uses. "For anyone in general and for women in particular to express anger, sexuality and violent sexuality, pain and pleasure, the things that are written all over her poetry, is quite unusual." Dropkin, who unapologetically and beautifully wrote and embraced sadomasochistic and deviant sexuality, was "no more marginalized than other women poets."

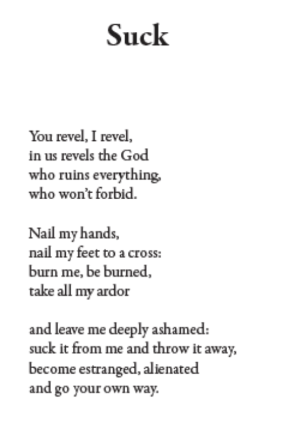

Thus, Dropkin's poetry remains a uniquely useful cultural artifact. It not only contains important information about the time period and society in which she was writing, but is still pleasurable for modern readers today. Weiman-Kelman sees Dropkin's work as "timeless, it is both direct in its address and expression, and is both raw but also very poetically sophisticated." The poem "Suck" shows Dropkin's playing with questions of sexuality, pain and pleasure while also engaging in a vivid and sophisticated way with Christian imagery.

Thus, Dropkin's poetry remains a uniquely useful cultural artifact. It not only contains important information about the time period and society in which she was writing, but is still pleasurable for modern readers today. Weiman-Kelman sees Dropkin's work as "timeless, it is both direct in its address and expression, and is both raw but also very poetically sophisticated." The poem "Suck" shows Dropkin's playing with questions of sexuality, pain and pleasure while also engaging in a vivid and sophisticated way with Christian imagery.

While Weiman-Kelman sees this project as being important on its own merit, they also hope that the exploration of forgotten, or erased, Yiddish histories is only the beginning of a lot of examination and work needed to be done in the Jewish community.

They hope that a reclamation of Yiddish can serve as a model that pushes us in the community to reflect on other aspects of the Jewish life and the relationship between the mainstream Jewish community and minority Jewish groups. They want folks to see this project and ask "what else haven't we been told? What else has been erased or stolen from us in terms of our history and what could be the significance of tracing other histories, be it Sephardic or Mizrachi histories, other histories of Jews of color, other things happening between the boundary between Judaism and other religions and cultures?" They emphasized, "It is really important to not stop with Yiddish."

Alec Weiker is a rising sophomore at Georgetown University and a 2021 HBI Gilda Slifka Intern.

Alec Weiker is a rising sophomore at Georgetown University and a 2021 HBI Gilda Slifka Intern.

Zohar Weiman-Kelman, a recipient of a 2021 HBI Research Award, is a senior lecturer in the department of foreign literatures and linguistics and holds the Blechner Career Development Chair in East European Jewish Culture at Ben-Gurion University.

Their first book, "Queer Expectations: A Genealogy of Jewish Women’s Poetry," was published by SUNY Press in 2018. (Photo credit: Neomi Itzaky)