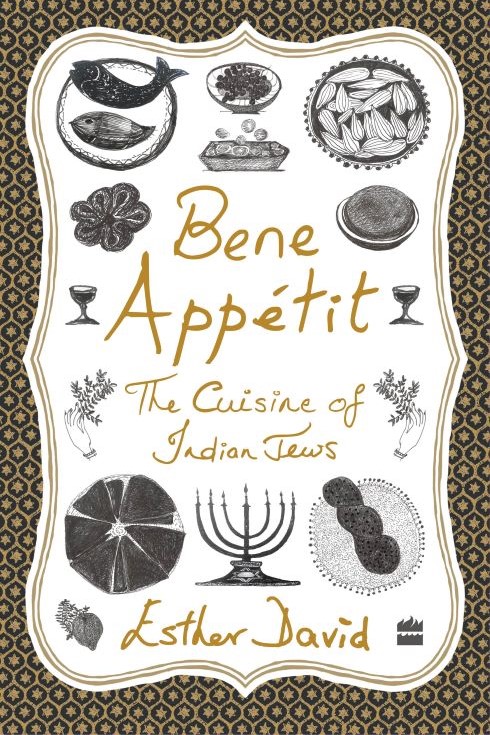

Bene Appetit — Cuisine of Indian Jews

Sept. 13, 2021

By Esther David

When my book "Bene Appetit — Cuisine of Indian Jews," was published by HarperCollins, readers wanted to know why I decided to write it. My answer is very simple. There are 5,000 Jews in India, down from about 30,000 at the peak in the mid-1950s and 1960s. When a community decreases in numbers, its traditional food starts to disappear. With this book, I have tried to preserve the heritage of Indian Jewish cuisine because food is memory and culture. Food is connected with the bonding of families and communities. Food is part of our childhood.

When my book "Bene Appetit — Cuisine of Indian Jews," was published by HarperCollins, readers wanted to know why I decided to write it. My answer is very simple. There are 5,000 Jews in India, down from about 30,000 at the peak in the mid-1950s and 1960s. When a community decreases in numbers, its traditional food starts to disappear. With this book, I have tried to preserve the heritage of Indian Jewish cuisine because food is memory and culture. Food is connected with the bonding of families and communities. Food is part of our childhood.

The Jewish community has been living in India since 75 CE and comprises a tiny but important part of the population. Many Jews settled in India after fleeing coastal areas of what is now Israel after the fall of King Solomon's second temple. They sough to avoid persecution from the Greeks. I used the word "Bene" in the title of the book, as it means "Children of Israel" in Hebrew.

There are five Indian Jewish communities — the Bene Israelis of western India, the Bnei Menashe Jews of Northeast India, the Bene Ephraims of Andhra Pradesh, the Baghdadi Jews of West Bengal, and the Cochin Jews of Kerala. Despite living in different corners of India, they are still bound by the common thread of food and religion. Over the years, members have stuck to the dietary laws and integrated Indian habits with their customs, leading to some unique ceremonies and rituals that have been passed down from one generation to another. However, with modernization and immigration, many of the traditions and recipes are fast being forgotten, hence the need to preserve them.

My narrative began as a journey to the five main centers of Indian Jewish life. This all became possible when I received support from HBI for the project in the form of 2016 HBI Research Award to study Indian Jewish food traditions. Since most Jews who came to India were fleeing persecution, they came to India through different routes and settled in different regions; choosing coastal areas. It was fascinating to note that Indian Jews of these five regions have different facial characteristics. When I photographed them, they became like a kaleidoscopic collage of contrasts and colors. Yet, a common thread bonds them together — their belief in Jewish traditions, rites, rituals, lifestyle and the dietary laws. I also discovered how Indian Jews preserve their food customs in a multicultural country like India, which has diverse food habits.

One of the uniting features of the Jewish Indian cuisine is the adherence to dietary law, much like many Jews of the diaspora. Jews do not mix milk with meat dishes and keep separate vessels for both. As yogurt is made with milk, and ghee (clarified butter) is used almostly daily in Indian homes, many Jews are vegetarians. It is also hard to find kosher meat due to a shortage of shohets (kosher meat slaughterer). Indian Jews have derived ways and means of using the correct regional ingredients to make festive food. Each community has a different culinary method, which is influenced by regional Indian cooking along with a distant memory of their country of origin.

I observed that each community had a different way of following the dietary law and rules of kashrut in their food habits. Yet there is a common thread which links each Jewish community to the other. Indian Jews who eat meat follow the law by not mixing dairy products with meat dishes. They have fish with scales and a taboo on pork. With meat dishes, they prefer to end their meals with fruit. As a substitute to dairy products, Indian Jews use coconut milk to make curries and sweet dishes.

Most Indian Jews live close to bodies of water, which influences their cuisine. They live around sea-shores, lakes and rivers and have a preference for fish and rice. Before, Indian Jews took to the urban way of life and moved to cities, they were farmers and owned paddy fields, along with coconut and banana plantations. The Bene Israel Jews were oil-pressers, but did not work on the Sabbath and were known as "Saturday-Oil-People." They settled in Maharashtra near the Arabian Sea. In Gujarat, Jews settled along rivers. Cochin Jews chose the Kerala coastline. While Baghdadi Jews first arrived in coastal Surat in Gujarat, they moved to Mumbai and eventually settled in Kolkata, along the Hooghly River in west Bengal. Bene Ephraim Jews chose the seashores of Andhra Pradesh, while Bene Menashe Jews of Mizoram and Manipur chose lakes and mountains.

An important factor of Indian Jewish cuisine is that many festive and ceremonial foods are made by the women at home or at the synagogue, under the guidance of a woman who knows the recipes. For example, kosher wine is not available in India so dried-grape sherbet is made for shabbat and festivals. The sherbet, (see recipe below) a traditional recipe for the end of Shabbat or Yom Kippur, is typically made with the women soaking black currants in a vessel of water and washing them, while the men crush, strain and bottle the sherbet. Men also tend to offer glasses of sherbet to the congregation at the end of the Shabbat or Yom Kippur prayers.

Challah was available at a Jewish bakery in Kolkata for Baghdadi Jews, but not elsewhere. So, Indian Jews tend to make flat bread or buy freshly baked white bread or buns. More recently, some women have learned to bake their own challah. In the same way, Indian Jewish women make flat-bread matzo for Passover along with charoset from dates and other ceremonial foods.

Indian Jews are proficient in English and regional languages, but chant their prayers in Hebrew. Since most Jews have immigrated to Israel, those remaining celebrate festivals together at the synagogue or at a rented hall and eat together like one big family.

To learn more about the recipes and customs of Indian Jews, read Bene Appetit which is available online or from your local bookseller.

Grape Juice Sherbet Recipe (traditional at the end of Shabbat or Yom Kippur prayers)

Ingredients

500 grams (two generous cups) dried black seedless grapes

One liter water

Sugar to taste (optional)

Directions

Wash the dried black seedless in a colander until clean. Soak them in a bowl of water from early morning to late afternoon (seven to nine hours). Then process in a mixer, strain through a thin muslin cloth or fine mesh strainer, bottle and refrigerate.

At sunset, the sherbet is poured into a goblet for the Kiddush prayers. The person who says the Kiddush sips sherbet from the goblet and passes it to a family and friends present. Sometimes, smaller shot glasses are filled with sherbet for guests. The sherbet stays fresh in the refrigerator for two days. Indian Jews make this sherbet because kosher wine is unavailable.

Esther David is a Jewish Indian author and illustrator, and part of the Bene Israel Jewish community of Ahmedabad. Her 2008 book, "Shalom India Housing Society," was published in the Reuben/Rifkin Jewish Women Writers Series, a legacy project of HBI and Feminist Press. Her novel, "The Book of Rachel," received the Sahitya Akademi Award for English Literature in 2010. She received a Hadassah-Brandeis Institute Research Award in 2016 for this research.

Esther David is a Jewish Indian author and illustrator, and part of the Bene Israel Jewish community of Ahmedabad. Her 2008 book, "Shalom India Housing Society," was published in the Reuben/Rifkin Jewish Women Writers Series, a legacy project of HBI and Feminist Press. Her novel, "The Book of Rachel," received the Sahitya Akademi Award for English Literature in 2010. She received a Hadassah-Brandeis Institute Research Award in 2016 for this research.