Jewish Ghosts and Why We Should Stop Looking for Them

Oct. 29, 2021

By Alec Weiker

How do we cope with that which we cannot understand? How can we manage when someone we know or love stops acting the way that we hope they would? Why do we desire to rationalize the manner in which our queer family or friends live their lives?

How do we cope with that which we cannot understand? How can we manage when someone we know or love stops acting the way that we hope they would? Why do we desire to rationalize the manner in which our queer family or friends live their lives?

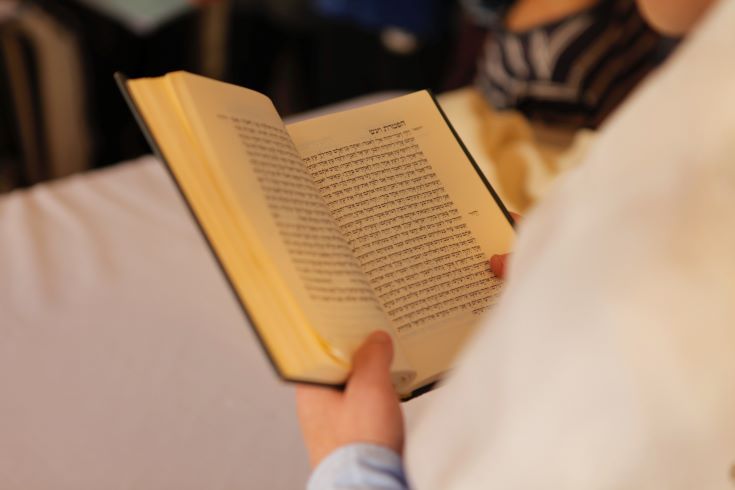

I didn't expect to encounter such questions this past summer while researching the phenomenon of the dybbuk in the Hasidic world, but they arose nonetheless. The dybbuk, a distinct figure in Kabbalistic mythology, was a uniquely nasty spirit–usually male–that possessed the body of young people, most often young women and caused erratic, strange, and transgressive behavior in its victims.

Numerous reports of dybbuk possession from across the Hasidic world were documented in both folk literature and more formal accounts of possession and exorcism written by rebbes. In fact, much of the knowledge we have of the dybbuk is based entirely on those reports written by men; this male control over the dybbuk narrative is key to understanding its function.

This can be seen most clearly through the case of the Maiden of Ludmir. Hannah Rachel Verbermacher, later known by the Maiden moniker, was a legendary figure who lived in 19th century Ukraine and became one of the most influential female Jewish religious leaders of the time. She attained a large following of both men and women and opened her own beis midrash (a house of learning), which was unheard of for a woman acting without the assistance of a man. Perhaps most transgressive for the time was her refusal to marry for the majority of her life.

Modern terms like lesbian or LGBTQ+ did not exist in the Hasidic world in this time, and we cannot aptly apply these labels to people living then either. Regardless of the Maiden of Ludmir's sexuality, she was queer in the broadest sense of the term, vigorously challenging and rejecting gendered power structures. By rejecting compulsory heterosexuality, the Maiden of Ludmir, at least in the eyes of her contemporaries, challenged the centrality and necessity of men. Further, in a society where religion was a central aspect of life, the abnormal and radical nature of the Maiden's religious leadership added to her queer identity.

Thus, despite her large following, the Maiden's success and gender nonconformity prompted many of her religious contemporaries’ disapproval. Rebbes reportedly alleged that the Maiden of Ludmir was possessed by a dybbuk who was using her to lead Jews astray. These accusations were mirrored by rumors of possession throughout the community.

Thus, despite her large following, the Maiden's success and gender nonconformity prompted many of her religious contemporaries’ disapproval. Rebbes reportedly alleged that the Maiden of Ludmir was possessed by a dybbuk who was using her to lead Jews astray. These accusations were mirrored by rumors of possession throughout the community.

The Maiden, however, not only denied claims of possession, but instead used similar theological terms to creatively resist. The Maiden claimed that she had received ibbur, which in contrast to the dybbuk was a positive form of possession in which the spirit of a male rebbe would enter into the body of a man, and exclusively a man, to assist him in completing a certain commandment. The Maiden claimed that she had received a "new and lofty soul" which helped her transcend her womanly boundaries to achieve religious prominence.

But the other rebbes rejected the Maiden's story. The cultural lexicon held no example of male ibbur occurring in women, while the dybbuk narrative seemed to fit much better. Thus, for a majority of the community, the dybbuk narrative negated the Maiden of Ludmir's ability to describe herself in her own terms. The discovery of this ghost explained away the Maiden of Ludmir's agency and blunted the societal impact of an inherently queer woman.

In addition to the Maiden of Ludmir, Yiddish stories used Jewish ghosts to explain excessive homosocial-behavior by a young man, lust in young women, and one woman's desire to inherit her father's position as an influential rebbe. In each case, the victims of possession, queer in their own way, are stripped of their agency and influenced, seduced, or forced to commit these transgressions by malevolent ghosts.

These examples depict a community that used familiar cultural idioms to explain and lessen the radicalness of gender nonconformity rather than directly engage with it. What struck me as I studied this function of the dybbuk was that American society seems to function in much the same way.

American culture obsesses over explanations, especially when it comes to queerness. Teens are using they/them pronouns because it's "trendy" or coming out as bisexual as part of a "rebellion phase," we're told. Additionally, people are quick to point to growing queer visibility in the media as the specter behind an increasingly queer-identifying youth. Besides negating the experiences and struggles of queer folks throughout history, these common explanations strip today's young queer folk of their agency by using the familiar societal narrative of the naive child.

It's easier for parents to blame gender nonconformity on external factors, or malevolent ghosts, than to imagine that their child doesn't fit their gender standards. But by taking something so complex and beautiful as queerness and forcing it into terms we understand, we take something away from it. Sexuality and gender identity are complicated and beautiful products of culture, identity, and behavior, and they can change based on time and place. Rigid labels are far too restrictive to capture that complexity. And that's okay. Queerness is inherently radical. It can't, and shouldn't, be simplified for our own comfort.

When we love someone close to us more than anything, we'll do almost anything in order not to lose them. We fear that we don't, or can't, understand a new aspect of a loved one, like queerness. We need a new narrative. Thus, the Maiden of Ludmir's story comes to us as a cautionary tale: if we go looking for ghosts, there's a good chance we'll find them. For those who could have found meaning and power in how Maiden creatively looked to re-envision the practice of Judaism, her delegitimization was an extraordinary loss. How much more meaning could we find in our own lives if we allowed ourselves to be surrounded by interesting people who we might not, or need not, understand?

But there's also an aspect of her story that can be extremely empowering for us as we navigate our queer identities in a heteronormative world. The Maiden of Ludmir, through her co-optation and subversion of a violent narrative, found empowerment on her own terms. Even if she wasn't successful in the eyes of her contemporaries, she made a space for herself to comfortably practice religious leadership, unfazed by the ghosts of convention.

Alec Weiker, a sophomore at Georgetown University, was a 2021 Gilda Slifka HBI Summer Intern. He researched the phenomenon of the dybbuk in the Hasidic world.

Alec Weiker, a sophomore at Georgetown University, was a 2021 Gilda Slifka HBI Summer Intern. He researched the phenomenon of the dybbuk in the Hasidic world.