Virtual Exhibition

Dana Arieli

Dana Arieli

Curator: Rotem Rozental

April 19 - September 30, 2021

The Schusterman Center for Israel Studies is thrilled to welcome you to our very first online exhibition! Take your time, explore the texts, delve into the images and create your own journey.

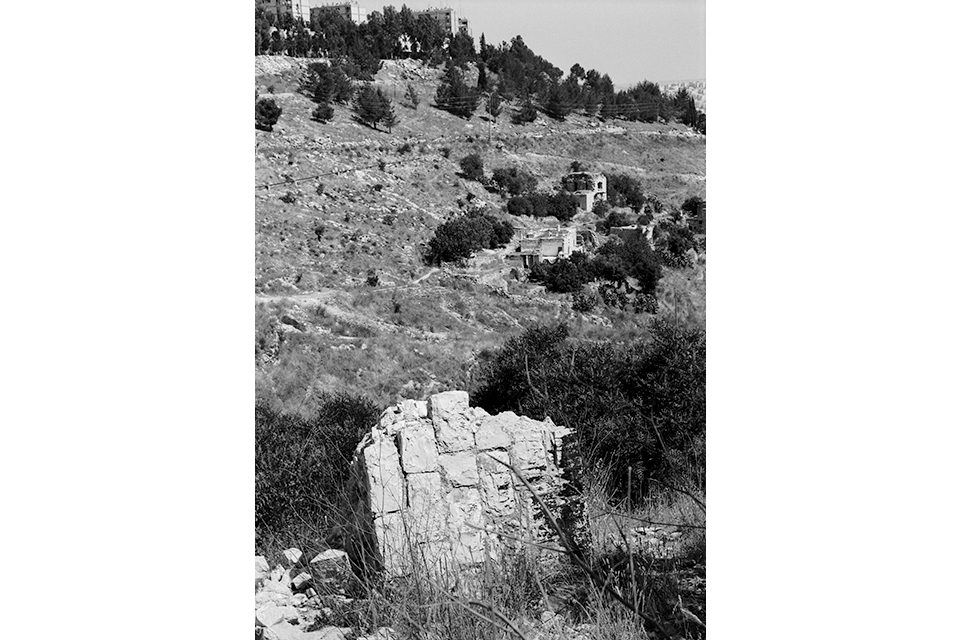

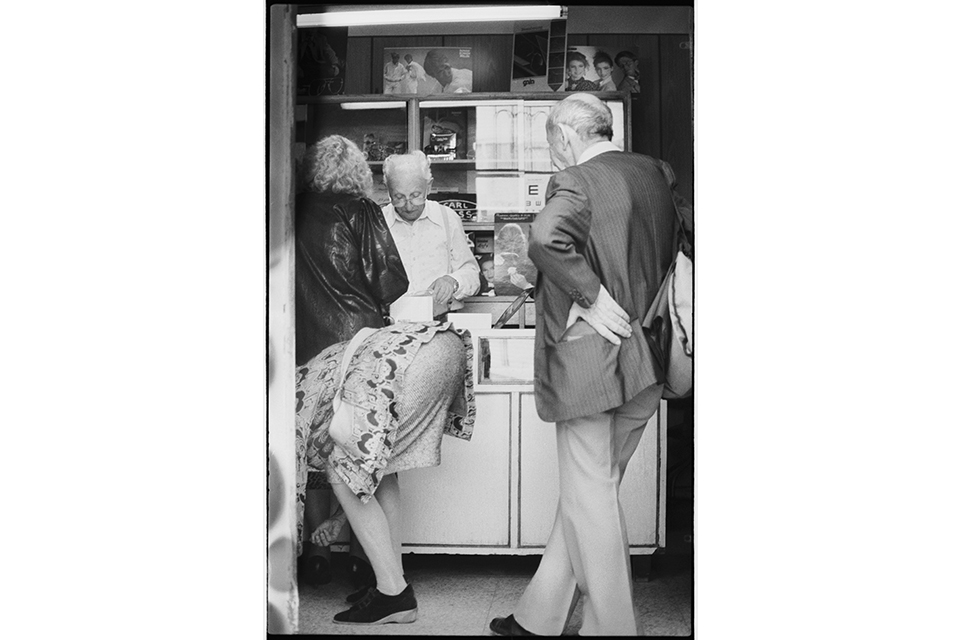

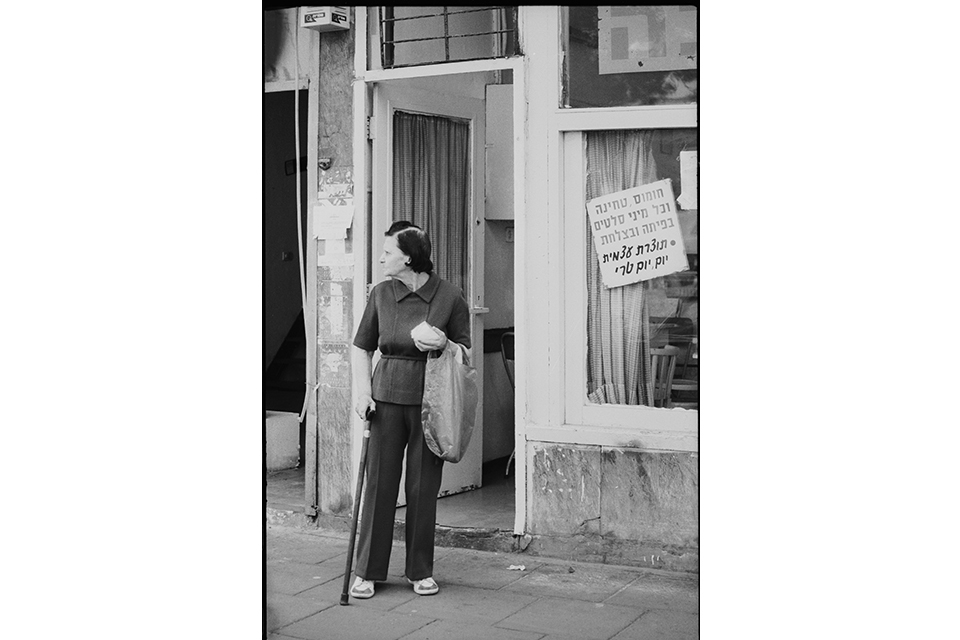

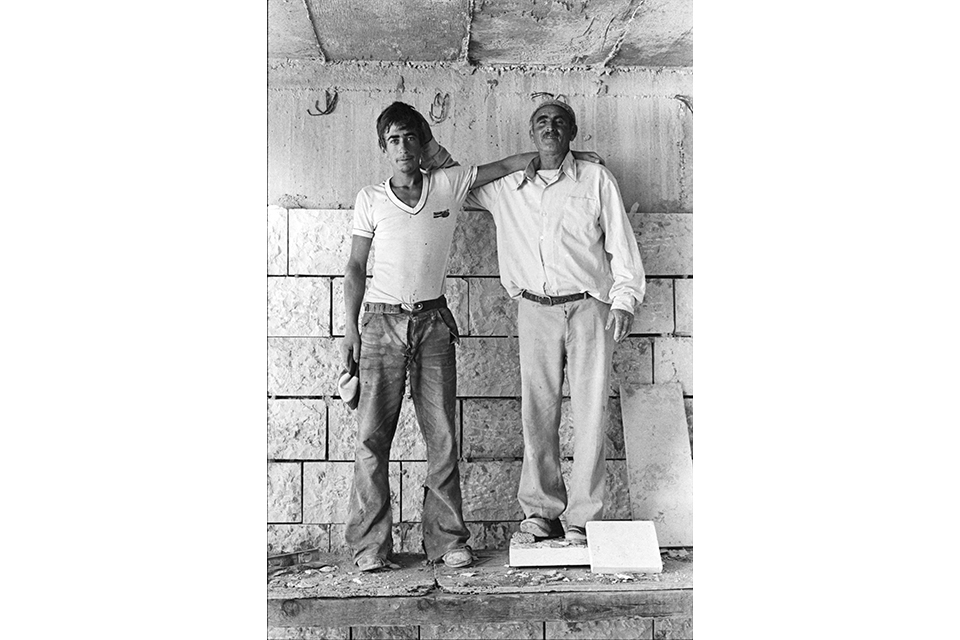

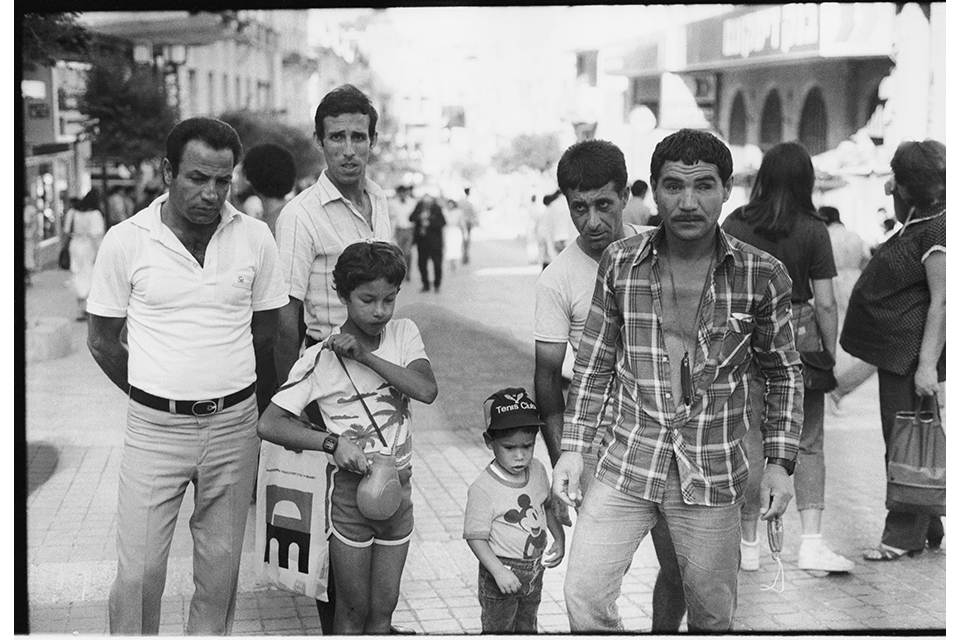

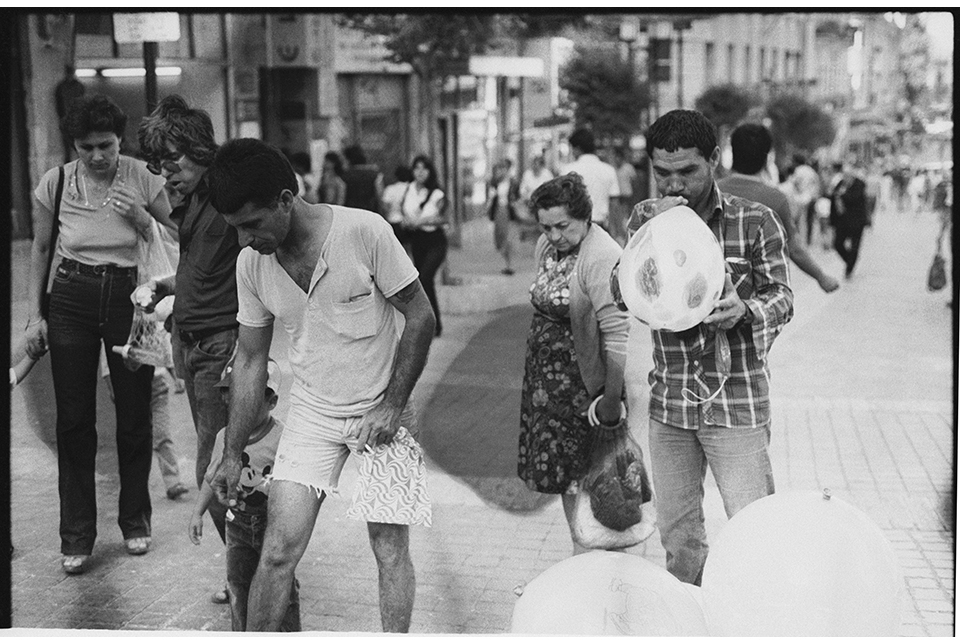

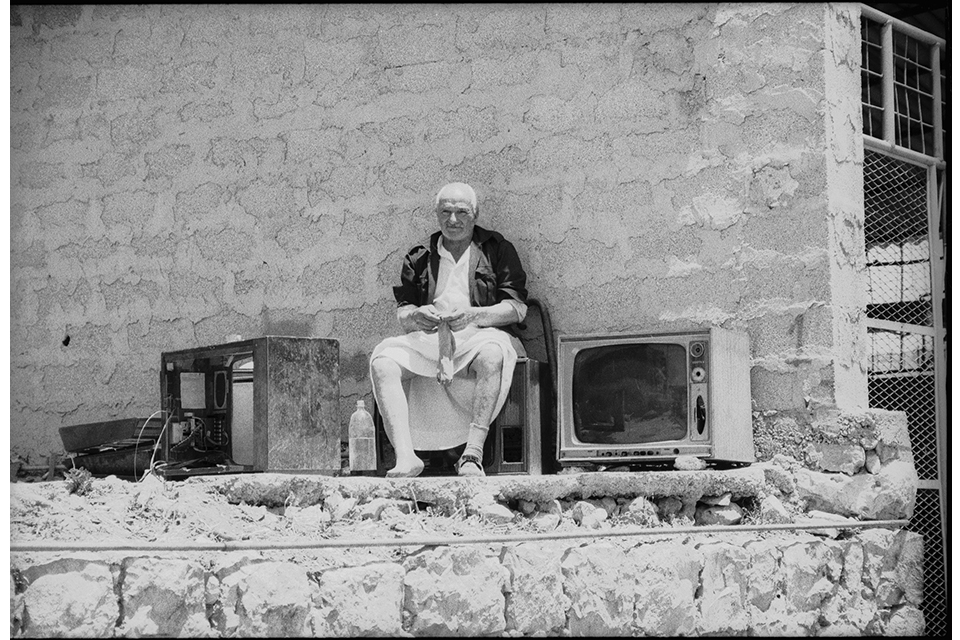

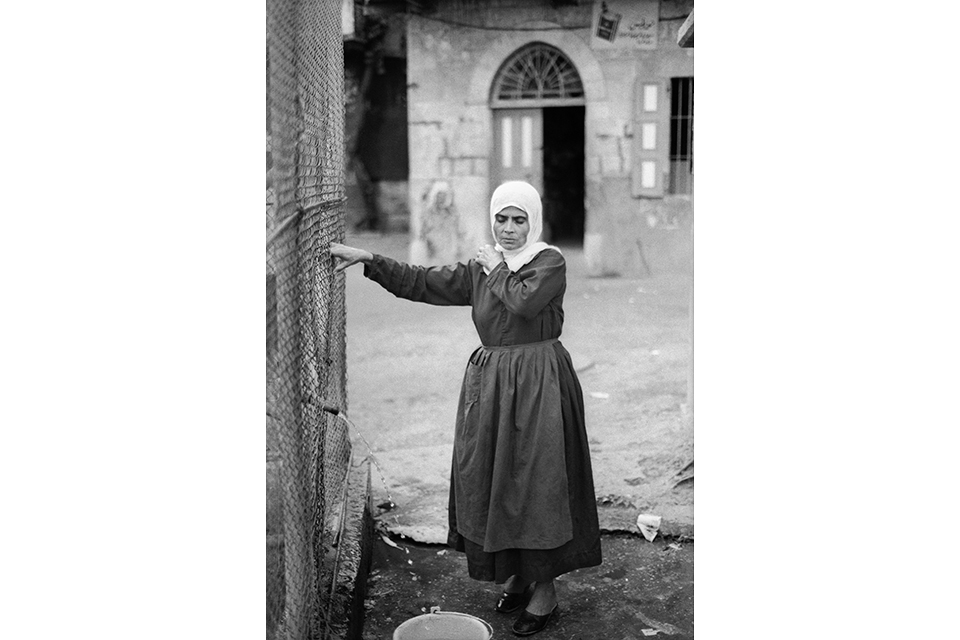

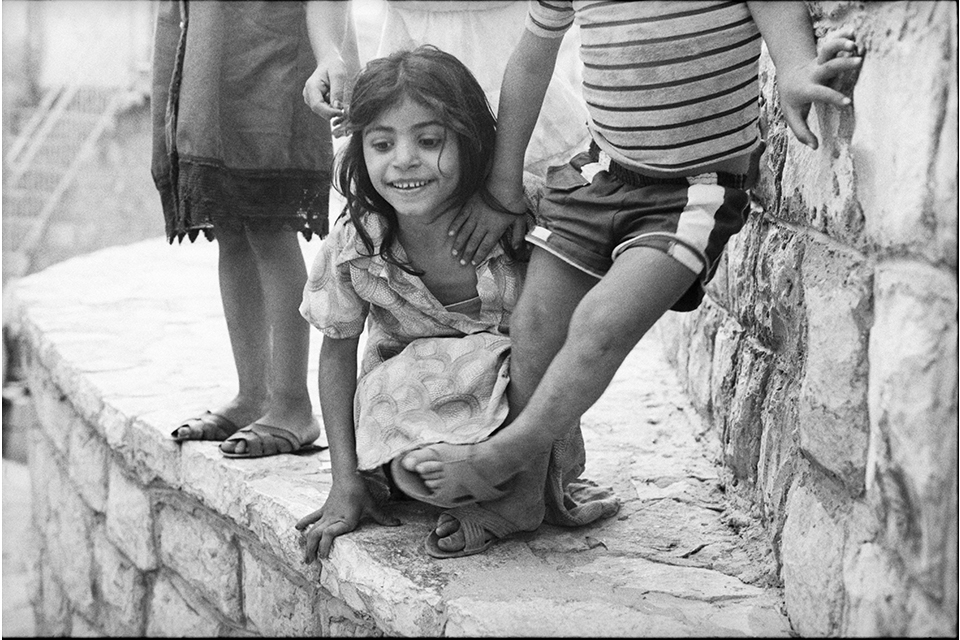

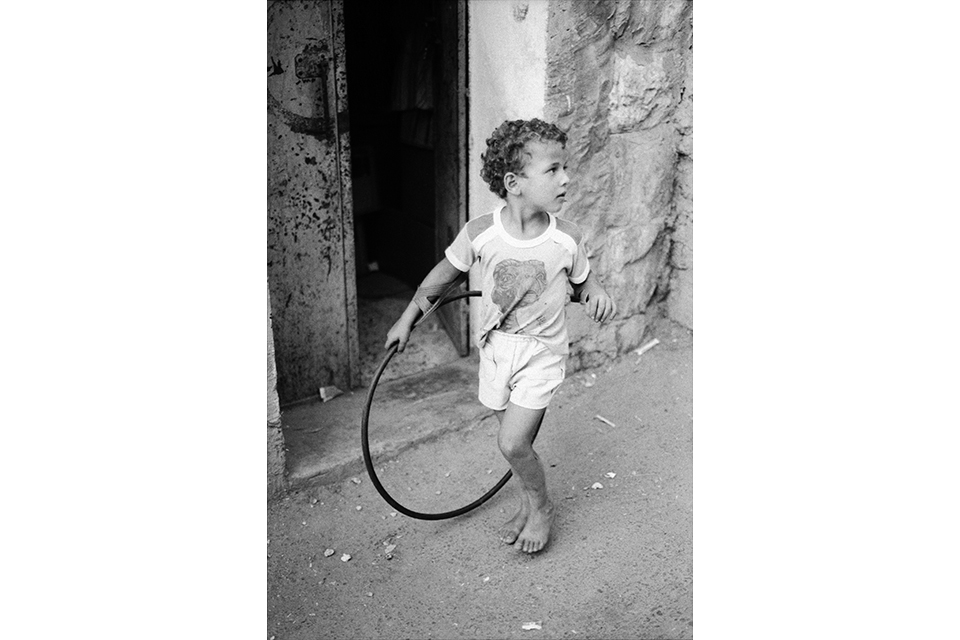

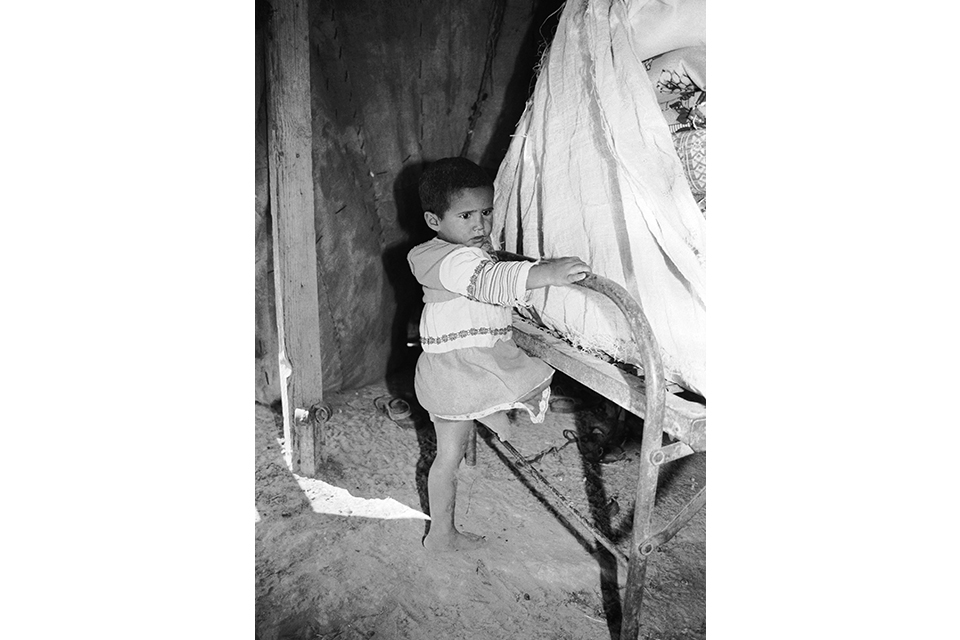

Through these images, Dana Arieli shapes a panoramic view of a landscape defined by its haunting ghosts, missing limbs, what should have been there and will never return.

View the image galleries:

- Disturbing Remains

- People with Numbers

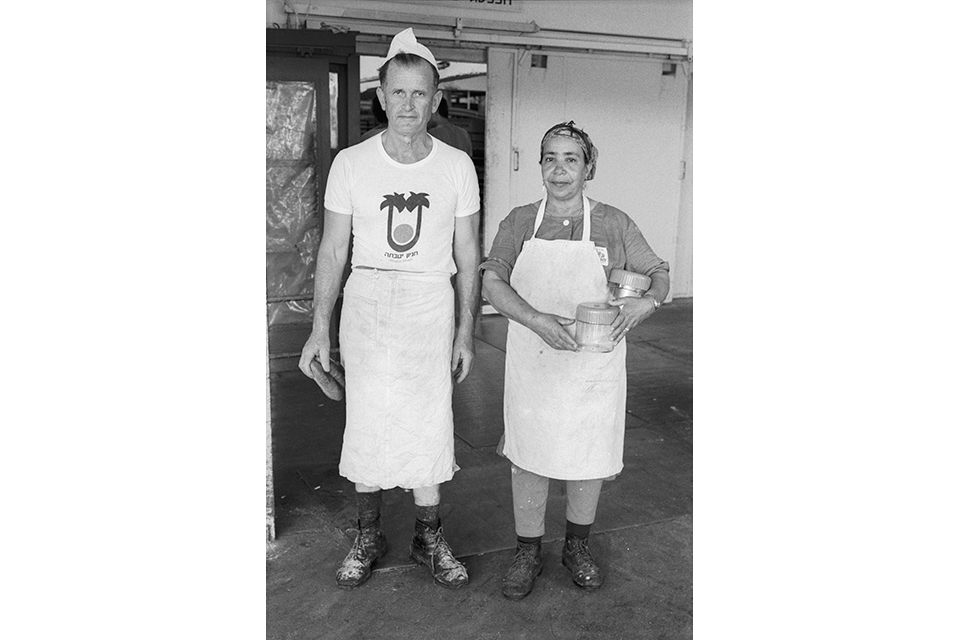

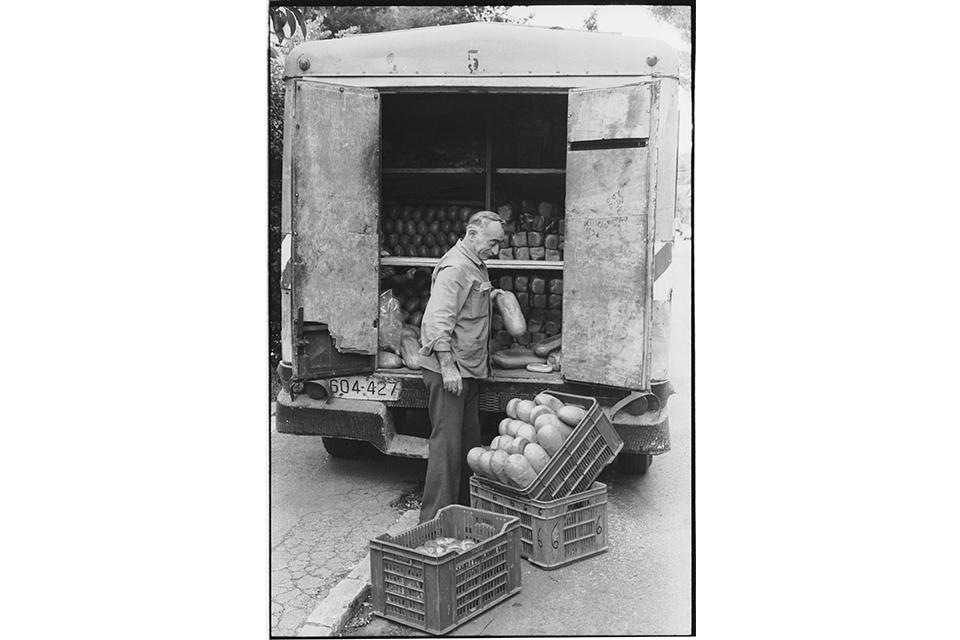

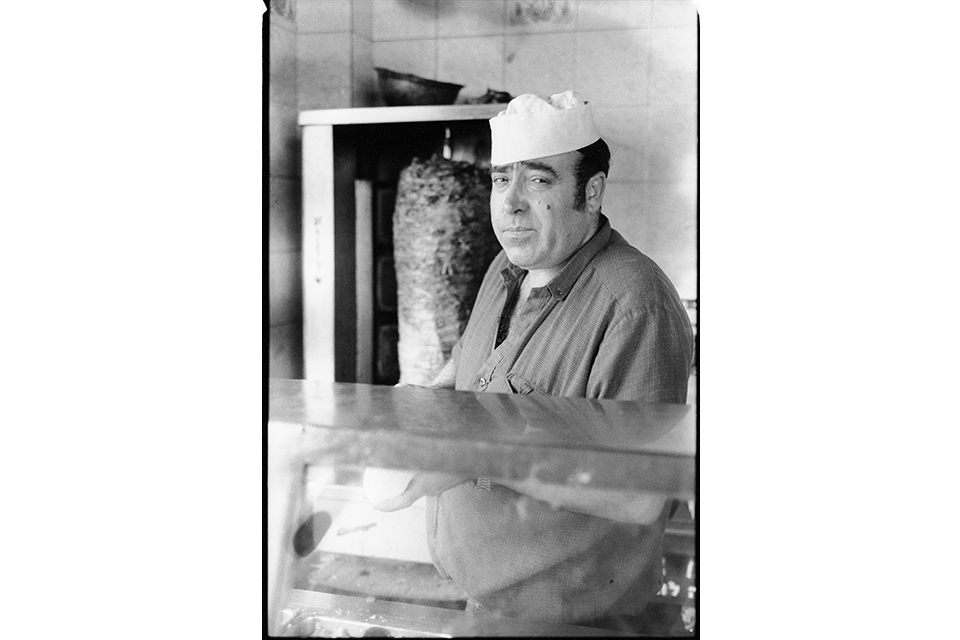

- Labor Movement

- Collection Houses

- Coordinates

- Youth Republic

- Vagabonds

Dive in:

- Curator text: "Is/Was: On Phantoms and Internal Malfunctions"

- Artist statement: "A Personal Lexicon"

Is/Was: On Phantoms and Internal Malfunctions

by Rotem Rozental

Collective Memories. Gray, cloudy skies are framed by geometric forms made of concrete: a cylinder connected to an oval by a rounded surface, another rectangle meets another rounded surface. There are markings in the rhythm of the concrete, textures, lines, change in tones. Perhaps it’s wet. Another image is occupied by concrete, flattening our point of view. Names of locations appear in Hebrew --Tze’elim, Hazerim, Halutza, Urim. Dotted lines have been carved, marking borders: a map embedded in stone. These close-ups offer partial views of Israel’s famous Monument to the Negev Brigade, designed by Dani Karavan. This site commemorates the fallen Palmach warriors who fought Arab forces in 1948, during the devastating war that followed Israel’s Declaration of Independence. Sprawling in the desert, the monument asks to underscore local history and continually recover it, eternalizing both a particular form of memory and itself as the embodiment of this memory. Although a caption tells us we are situated at the monument, it is unrecognizable in these images. At the same time, it seems eerily familiar. We remain trapped between the brutalist geometric shapes that define (or block) our view.

The Zionist Phantom: A Personal Lexicon

by Dana Arieli

Phantom/Phantoms

The French word “fantôme” means “ghost” or “visual illusion.” Dictionnaire de la langue Française by Emile Littré defines the word as “fictitious entities that engage the imagination” or an “image of the dead that usually appears in a supernatural way.” The word “phantom” is a distortion of the ancient Greek word “phantasma, meaning a ghostly apparition.”

The attempt to capture ghosts is doomed to failure, or, at the very least, is complex and elusive. Psychologists use the term “phantom pain” to depict the physical pain amputees experience arising from their body and psyche. When I visit a battlefield, like Tel Saki in the Golan Heights, I can almost feel the phantom pains of the wounded.

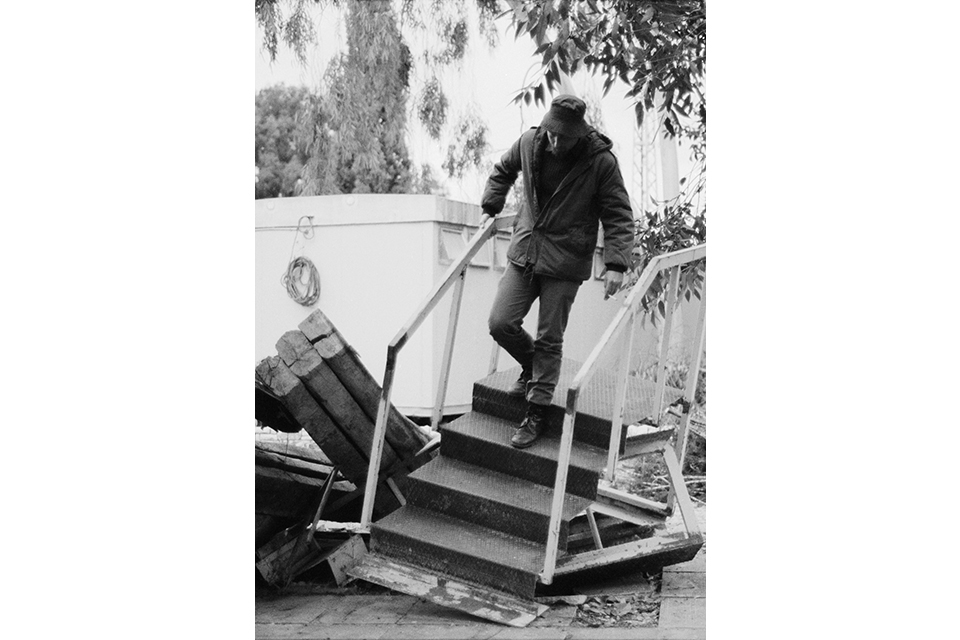

I don’t believe in ghosts, and do not try to document them. I am interested in the remains left behind by history. In the Zionist Phantom project, I was drawn to research trauma caused by political power, or by protest against it.

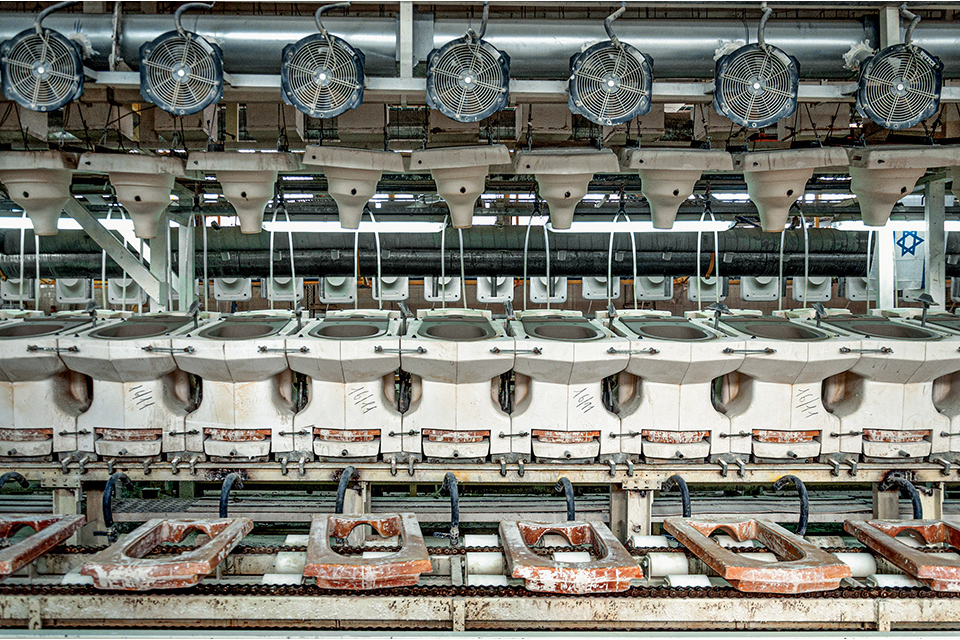

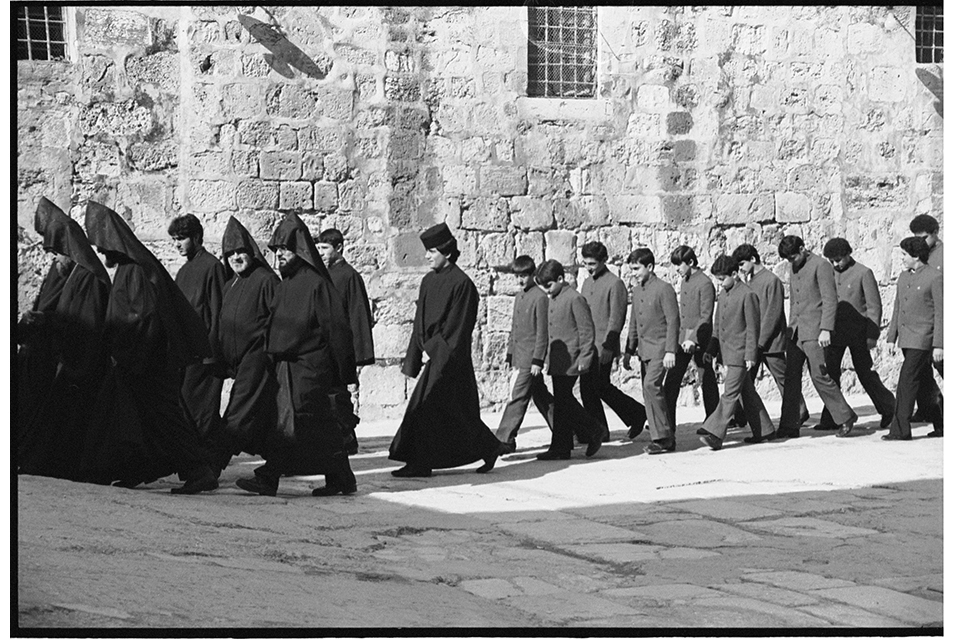

A decade ago, I began documenting relics of dictatorships and, throughout this time, continued documenting in Israel. In both of these projects, I was drawn to exploring trauma caused by political power. I document relics of wars, abandoned places, and contested sites. There are also moments in this project when the link to the Phantoms is more illusive such as in the photographs of the Hebrew University campus or factories. I feel that they are suitable here because they lost the central position they once occupied in Zionist ideology.

The Zionist Phantom

I chose this title because it often seems to me that the Zionist ideology has too rapidly became a ghost. I document the remains of Zionist ideology, its institutions and symbols, those that glorified the public sphere and have lost their former glory. I ask myself whether the many controversies that exist in Israeli society harm the symbols of Zionism. The Zionist Phantom project documents the fragmentation characterizing Israeli society.

Someone once asked me if the project expresses my sense of bereavement at how society has changed. I have no clear answer to this, but I do think about her question again and again because I am unable to discard this hypothesis.

I can’t remember any project where it took me so long to finalize the title. Usually they appear and, as time goes by, they become more and more suitable. Here, the exact opposite happened. I met people who told me they were unable to participate in the project because I identify as a researcher and a photographer of phantoms in dictatorships and, as they see it, the “Zionist Phantom” hints that Israel is an undemocratic country. Like many of the country’s citizens, I am extremely troubled.

More than once I have found myself drawing parallels between the Weimar Republic, which I have been researching, and contemporary Israel. However, this title was not selected to hint we are on a path to dictatorship, although the current situation is more complicated than ever.

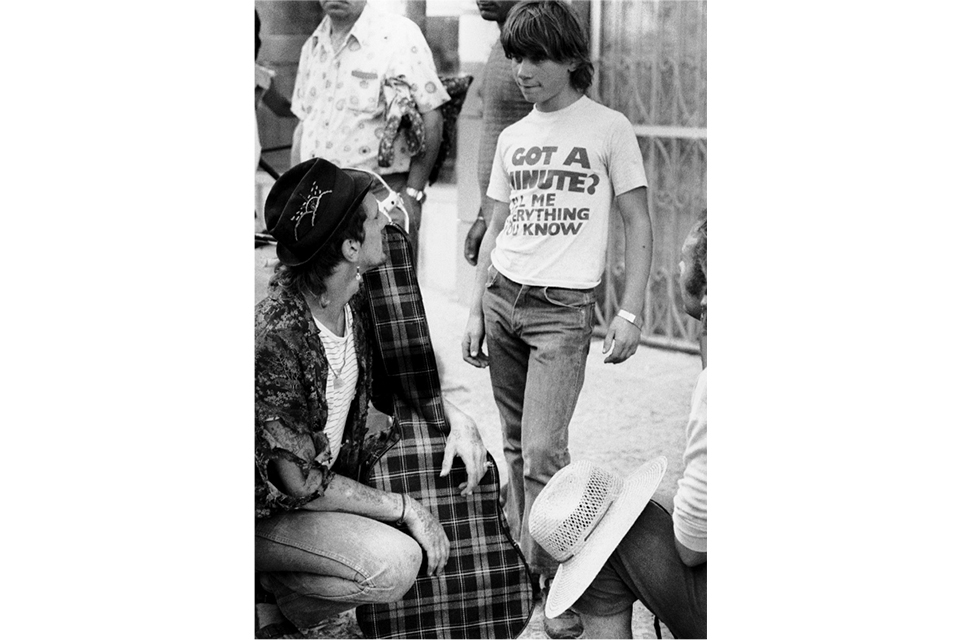

Your Viewpoints

Since I believe my viewpoint emerges from the photograph, I find it easy to leave the writing to others. Here, your viewpoints encounter mine. I have already done this in the past in my Phantoms project dedicated to the remains of dictatorships.

I invited participants in workshops and visitors to my website to contribute texts about my photographs, to refer to them in any way that comes to mind. Although texts are not censored, they have been edited prior to publication.

I asked you, the writers, to refer to a photograph that you connected with. It was important for me to connect with anyone who is interested in this place, in its culture and its photographic documentation, and not necessarily only with curators, artists and scholars. This collection includes texts that express different points of views, which fascinate me. All of the texts contributed to this project are available in the Zionist Phantom website, and it will continue to grow with each contribution.

Instead of an Archive: A Box of Photographs with a Notepad

More than 50,000 photographs were collected as part of the Zionist Phantom project. They require archival stewardship on a continuing basis: searching, classifying, cataloging, and numbering, creating typologies. I gather all of this data in numerous pads and notebooks where I search for the logic in all of this. I love to sort, because this reminds me of an early childhood memory: Granny used to ask me to sort all of the buttons that she collected in her large button box.

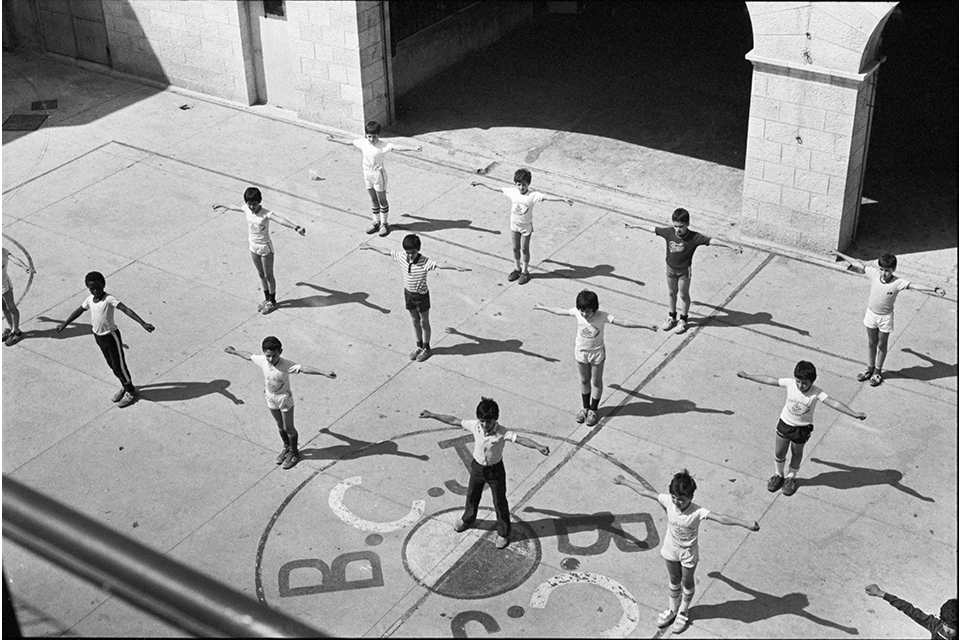

My viewpoint

I was born with a “lazy eye,” a reduced vision in one eye, caused by abnormal visual development. It took me years to realize that I photograph on a tilt because that’s how I see. That’s the reason that I love to use wide lenses, such as the Fisheye lens. They distort the picture, which is my preferred state. This is also the reason why it’s hard for me to focus — not only in photography. I realized this when reading Max Nordau’s book Degeneration (1892–3). Among other subjects, he wrote about the Pointillists, who broke up images into small dots because they suffered from nystagmus, rapid movement of the pupil. At first I tilted the camera and the angle became more extreme but, even now that I am aware of this, my photographs still come out tilted, no matter how much I try to make the frame straight.

I always look for the contour — the general outline of the subject being photographed. I have various points of view: “lazy,” crooked, or broken. That is why, in the majority of cases, the accepted or “institutional” perspective is broken. I prefer an overview and close-ups that disrupt the conventional viewpoint and appearance of what shows up in the frame. In places that are too orderly, I try to create disruptions. Perhaps that is the reason why I find it challenging to perform processes intended to “repair” or “beautify” reality.

Intuition

My Phantom photographs began with hope mixed with cynicism. “Fotografie Macht Frei,” I told myself, convinced that this creation would at last allow me to finalize this chapter of the research. But that did not happen. A single journey following phantoms turned into dozens of journeys around the world – and throughout Israel.

When I photograph I find myself in a time capsule. It requires me to have complete focus because I try to imagine the past of the site. I invite the dead to dine, wrote Amit Gish. I search for signs of trauma.

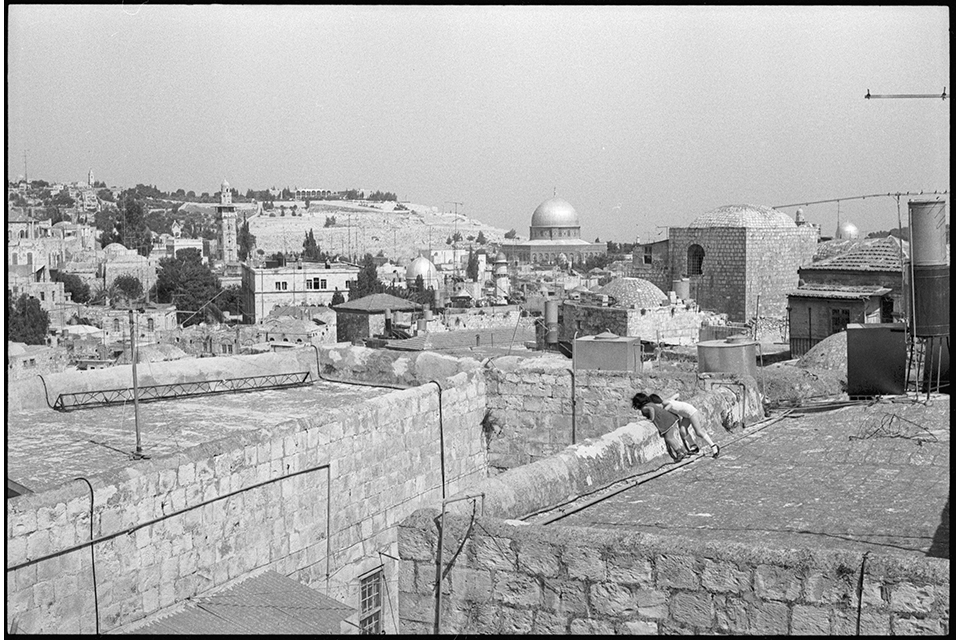

Place

The “Zionist Phantom” website comprises more than 90 entries, each of which references a different geographical location. I attempted to bring at least one image from each place to this collection of photographs but, in practice, I did not succeed and found myself choosing more and more photographs from Jerusalem. In these selections, I integrated texts that I love within the framework of the larger project.

When I create photographic series, I frequently use maps. The photograph begins in a place, in a geographical coordinate I set out to document. The location presents me with challenges: climbing a fence, kneeling, holding my breath, coping with heat or cold, fatigue, wonder, astonishment, unpleasant odors. A day of shooting takes many, many hours after which there is no chance I would ever forget the location of the site. The method of cataloging by location assists me in building the archive. At the end of the shoot, or the next day, I remind myself that it is critical to copy the photographs from the memory card to my personal archive. Finally, one or two photographs receive a red dot. Hours upon hours of searching and hoping to find one single frame to tell the story of the place.

Memory Culture

The memory culture in Israel is not homogeneous. It appears in innumerable forms. When observing the commemorative sites too numerous to count throughout Israel, one finds places dedicated to wars, terrorist attacks and car accidents. It is evident there is no singular way to outline a historical narrative. At times, narratives can collide in the same site. There is a dark tourism in Israel: memory culture that is anchored and driven by grief, which leads families to visit cemeteries. The Zionist Phantom engages with memory culture: this project is devoted to the way in which we remember or forget our past, to the way in which structures and objects unfold the historical narrative.