Marcia Freedman's Life Showed That Change is Possible

Oct. 19, 2021

By Orly Nathan

Marcia Freedman, a former member of the Israeli Knesset, and one of the founders of the feminist movement in Israel in 1970s, passed away Sept. 21, 2021. Best known for her activities related to reproductive rights and the elimination of violence against women, Freedman also tackled other controversial issues, such as secret arms deals with Apartheid-era South Africa, legalization of soft drugs, teenage prostitution, incest and breast cancer. She was one of the first to raise the issue of LGBT rights and put it on the agenda of Israeli politics. Freedman, as a radical feminist, recognized very early on "the decisive role of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the development Israeli feminism," as noted in her book, "Exile in the Promised Land."

I am the Elaine Reuben '63 HBI Jewish Feminism Collections Scholar in Residence at HBI this semester and my research is focused on the Marcia Freedman archive in the Brandeis University Jewish Feminism Collections, one of the two sites to which Freedman bequeathed her private collections. The archive ranges from the start of her activity in Israel until the 2000s. Freedman's papers are also held at the Feminist Archive at the Research Center of "Woman to Woman" organization (Isha l’Isha), where she was one of the founding mothers. It is part of a collaborative partnership with Brandeis.

I came here to explore the history of Israeli feminism, or rather the "herstory" that is still unfolding, relevant and contemporary, and should be learned so that it will continue to inspire the ongoing feminist activity of today. Right now, my aim is to gain a deeper understanding of Freedman's thorough, dedicated work and her ability to see clearly and soberly, even at that time in Israel when there were structures of oppression and exploitation in all spheres of life (especially militarism and nationalism). My goal is to put Freedman, along with her friends in the "Movement for the Liberation of Women," on the public agenda in order to bring about some of the changes they started.

Born and raised in Newark, New Jersey, to Anne (Silver) Prince, a homemaker, and Philip Prince, a union organizer, Freedman always admired her father's path and dedicated her memoir "Exile in the Promised Land" to her father, "whose example I have largely followed." She graduated from Bennington College in 1960, earned an MA in philosophy from Brooklyn College, and took part in the civil rights movement. She married Bill Freedman, a lecturer in English, and gave birth to their daughter, Jennifer. In 1967, the family immigrated to Israel, where Freedman taught philosophy at the University of Haifa. Her personal revolution occurred in 1970 after her father committed suicide. Following this personal crisis, Freedman's depression and accumulated anger sent her back to the feminist books she had purchased in New York and hidden from her husband. In her book, "Exile in the Promised Land," she wrote:

Born and raised in Newark, New Jersey, to Anne (Silver) Prince, a homemaker, and Philip Prince, a union organizer, Freedman always admired her father's path and dedicated her memoir "Exile in the Promised Land" to her father, "whose example I have largely followed." She graduated from Bennington College in 1960, earned an MA in philosophy from Brooklyn College, and took part in the civil rights movement. She married Bill Freedman, a lecturer in English, and gave birth to their daughter, Jennifer. In 1967, the family immigrated to Israel, where Freedman taught philosophy at the University of Haifa. Her personal revolution occurred in 1970 after her father committed suicide. Following this personal crisis, Freedman's depression and accumulated anger sent her back to the feminist books she had purchased in New York and hidden from her husband. In her book, "Exile in the Promised Land," she wrote:

Reading and studying "were not theoretical learning about a new social cause. It was about me, and my entire life was in question. Why do I do all the housework? Did I really ever choose to become pregnant? … Why did I take on Bill's name when we married… Why am I the only woman in the philosophy department? Why am I unable to finish my doctorate?… My friend's PhD document hangs on her kitchen wall, above the sink, where she can look at it each evening while she does the dishes. Such moments are historical markers of developing feminist consciousness."

Freedman realized that anger is a rational response to oppression; that an imbalance of power determined her relationship with her husband, child and colleagues at the university. She learned that like all oppressed peoples, women would have to resist and fight back, not individually but collectively. Slowly she began to gather around her a group of women, first in Haifa and later throughout the country, who shared her feminist perspectives and created the consciousness-raising groups that became the foundation of the women's liberation movement in Israel in 1972.

In the post-war elections of 1973, the movement helped Shulamit Aloni, a left-wing champion of civil liberties, and her Ratz party (a forerunner of today's Meretz ), known as the Civil Rights Movement, gain three seats in the Knesset. Freedman was third on the list (so was not considered likely to win a seat) and became an MK. She was chosen by Aloni, who in those years was the familiar public face of the new feminist movement. As a member of the Israeli parliament, Freedman was a voice of women's issues and put a variety of topics which were violently silenced at the time (and even today) on the legislative agenda. It took her more than two years to make history when she convened the first Knesset session dedicated to domestic violence against women in 1976.

In the Brandeis archives, I have found the Freedman's thorough notes and data on the extent of violence against women from the Women’s organization — WIZO and the Citizen Counseling Service. She published ads in all the newspapers and asked women to write testimonies about their husbands' violence. The letters came in the dozens from all over the country and from women of all social classes. The descriptions were horrifying, but what mostly caused the women's sense of helplessness was the disregard, contempt, disbelief and abandonment of the establishment, especially the police and the rabbinical courts. All of them described feelings of shame trying to hide the terror they lived in from their families. Most even wrote suggestions and ideas of ways to deter husbands from violence.

Marcia Freedman's brilliant and brave speech in the Knesset was constantly interrupted by chauvinistic, offensive shouts, trying to deny the very existence of this widespread phenomena. The police minister said the police "couldn't interfere in a married couple's relationship" and demanded that the issue be stricken from the agenda. But, Freedman gained a majority of votes in the Knesset so that her proposal was able to advance to the agenda of the Interior Committee. This was first public acknowledgement in Israel of family violence of against women.

In a news-obsessed country such as Israel, the commotion reached every household. As a young schoolgirl, it had a profound impact on my identity, views and future activism. During the debate, Freedman and her colleagues presented recommendations for the proper handling of women's complaints. One important recommendation — not yet implemented to this day — was the appointment of a female social worker to accompany the plaintiff women to court in domestic violence cases

Freedman was the first to propose the establishment of a shelter for battered women. Following the debate, the police created a special research team, and the subject was supposedly transferred to a special subcommittee, but there is no record of this subcommittee having ever met, and no report was ever issued. The government fell in February of 1977 and all the Knesset committees were dissolved with no further action. Freedman said in an article published in Ynet 2007:

"My idea was to set up a shelter for battered women and show that the phenomenon exists, and not turn the shelters into places of treatment. In my opinion, the treatment should be separated from the fight against violence. Battered women should be given much better conditions than those they have in shelters."

Freedman is perhaps best known for her role in promoting reproductive rights for Israeli women. One of the important events that Freedman initiated was a protest at the annual conference of gynecologists in 1976, titled "Ethical Aspects of Birth Planning." At the Tel Aviv Hilton, 11 women protestors carried signs calling for legalizing abortion and giving women autonomy over their bodies. A gynecologist threw a pitcher of water at her, including the pitcher itself. Freedman said that the doctors opposed the liberalization of abortion laws and at the same time profited from performing illegal abortions. Police officers violently dispersed the demonstration.

Freedman is perhaps best known for her role in promoting reproductive rights for Israeli women. One of the important events that Freedman initiated was a protest at the annual conference of gynecologists in 1976, titled "Ethical Aspects of Birth Planning." At the Tel Aviv Hilton, 11 women protestors carried signs calling for legalizing abortion and giving women autonomy over their bodies. A gynecologist threw a pitcher of water at her, including the pitcher itself. Freedman said that the doctors opposed the liberalization of abortion laws and at the same time profited from performing illegal abortions. Police officers violently dispersed the demonstration.

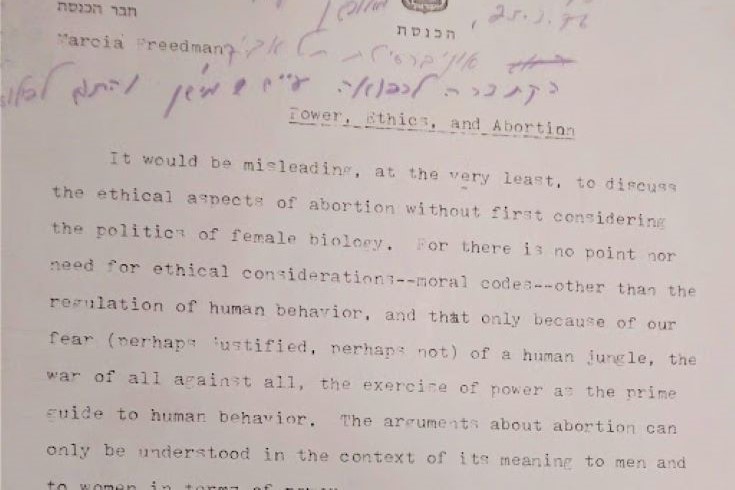

Two opposing proposed laws were discussed at the time: a conservative law leaning towards religious leaders' views, and another proposed by Freedman and Nitza Libai-Shapira, based on the U.S. Roe V. Wade model. Freedman prepared for the hearings as though defending a doctoral thesis. I have found her draft paper among the folders in the Brandeis archives. This is the a quote from the opening paragraph: "Power, Ethics, and Abortion — It would be misleading, at the very least, to discuss the ethical aspects of abortion without first considering the politics of female biology. … The arguments about abortion can only be understood in the context of its meaning to men and to women in terms of power…"

The conservative law proposal, that women could not have abortions without the approval of a committee, was eventually adopted with minor amendments, however in the long run the criteria became more flexible. Yet even today, Israeli woman do not have the right to decide, and they must face a committee with the authority to approve or deny abortion. Freedman advocated for free abortions without a committee decision, without conditions during the first trimester, and with support for women from social workers and medical professionals.

In her 40s, after Freedman left the Knesset, she divorced her husband and publicly came out as a lesbian. Back in Haifa, with other feminist friends, she got busy. In addition to the first shelter for battered women, they opened a feminist center and bookstore, "Kol Haisha" Books, Freedman recalled, "were a very central tool for promoting feminism in Israel." Some of the books were later found to be tagged under "Sex" in Steimatzky, Israel's leading bookstore, she said.

In 1977, Freedman co-founded the Women's Party that ran in the Knesset elections, but did not win any seats. The platform of the party in English and Hebrew can be found in the Brandeis Feminism Collection and the Feminist Archive at the Research Center of "Woman to Woman."

Freedman came back to the United States in 1981 and settled in Berkeley, California. She returned to Israel for extended stays from 1997 to 2002, helping to co-found the Community School for Women, which offered courses in women's studies and employment skills to underserved women, and was involved over the years in a wide array of social and political initiatives in U.S. and Israel, including Bat Shalom and Brit Tzedek v'Shalom, a pro-peace group that merged into the J Street lobby in 2010; and the Gun Free Kitchen Tables (GFKT) Coalition, working for stricter gun control in Israel.

A year ago, at a Zoom meeting, Hannah Safran asked Freedman how she sees the past 50 years. Freedman replied: "I'm 82. Looking back, I feel grateful. I had an interesting life, I had a meaningful life, I had a very good life."

May her memory be a revolution.

Learn more about Nathan’s work on Marcia Freedman papers in the Brandeis Feminism Collections during her seminar, She Knows: Using the Brandeis Feminist Collection Archives to Explore the History of Israeli Feminism, at 12:30 p.m. Nov 1.

Orly Nathan is the Elaine Reuben ‘63 HBI Jewish Feminism Collections Scholar in Residence. She is an Information professional and a feminist activist. She is the chief information specialist of She Knows (Yoda’at).” at the Samuel Neaman Institute at the Technion.

Orly Nathan is the Elaine Reuben ‘63 HBI Jewish Feminism Collections Scholar in Residence. She is an Information professional and a feminist activist. She is the chief information specialist of She Knows (Yoda’at).” at the Samuel Neaman Institute at the Technion.

Elaine Reuben, Brandeis ’63, is a member of the HBI Board of Advisers.