Leader of Ford Hall Takeover to Receive Alumni Achievement Award

October 9, 2015

By Emily Evans

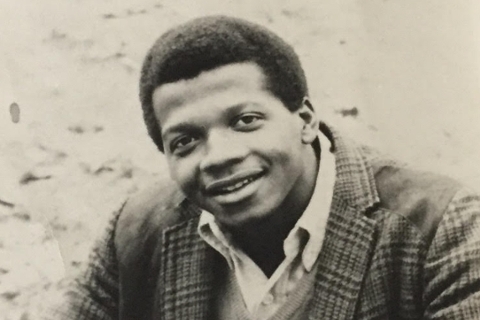

No revolution ever found its footing by playing it safe. Just ask activist Roy DeBerry ’70, MA’78, PhD’79.

DeBerry has dedicated his life to righting the wrongs he sees in society – from his native Mississippi to the Brandeis campus, where he staged a demonstration at Ford Hall in 1969. DeBerry and fellow honoree Susan Weidman Schneider ’65, founder of the Jewish feminist magazine Lilith, will receive Brandeis’ Alumni Achievement Award during Fall Fest at 4 p.m. on Saturday, Oct. 24.

When DeBerry arrived at Brandeis in the fall of 1966, the civil rights and anti-war movements were in full bloom. “We had moved away from the quiet ’50s to the turbulent ’60s,” he says during a phone interview from Mississippi. “The whole country was full of activity, and Brandeis was caught up in that. We didn’t want to sit back and do nothing; there were things that we could do for all students of color – not just black students. Sometimes you have to be a catalyst for change.”

And a catalyst for change he was. In the spring of 1967, DeBerry and fellow students in the Brandeis Afro-American Society delivered a series of demands to the University, including the establishment of an African-American studies program, the hiring of additional black faculty and the recruitment of more students of color. The demands were not met immediately, but after the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968, a renewed energy for change occurred on campus.

On Jan. 8, 1969, about 70 African-American students, led by DeBerry and other student leaders and advisers, staged a demonstration by occupying Ford Hall, the central academic building on campus. The students again presented the administration with their list of demands, and they refused to leave Ford Hall until the demands were met. The occupation focused national attention on Brandeis, student demonstrators and President Morris Abram.

“I didn’t know then that the occupation was going to be so impactful,” DeBerry says today. “When you’re in action, in the heat of battle, you just focus on your goals. It felt empowering.”

For 11 days, the protesters occupied Ford Hall, sleeping, eating, meeting and negotiating in the building. Faculty, staff and students provided supplies. Finally, on Jan.18, 1969, the students left after two thirds of their demands had been addressed.

“In the moment, you think you can get 100 percent of your demands met,” DeBerry says. “But negotiations are give and take. I think the occupation of Ford Hall was a success not just for us, for the black students, but for Brandeis. The occupation was about change for the University – change for the better.”

When he returned to Brandeis more than a year after graduation to pursue his graduate degree in politics, the changes brought on by the Ford Hall occupation were evident to DeBerry. There was a Department of African and Afro-American Studies led by a person of color. There were accomplished people of color on the faculty, more women, and additional Asian, Hispanic and black students on campus.

When he returned to Brandeis more than a year after graduation to pursue his graduate degree in politics, the changes brought on by the Ford Hall occupation were evident to DeBerry. There was a Department of African and Afro-American Studies led by a person of color. There were accomplished people of color on the faculty, more women, and additional Asian, Hispanic and black students on campus.

DeBerry credits Brandeis with giving him the support to question the status quo: “I’ve always had a healthy skepticism, but Brandeis enhanced it. I learned early in life to question things like apartheid, caste systems and segregation. At Brandeis, I honed those skills.”

DeBerry was already a seasoned activist by the time he arrived at Brandeis. As a teenager, he took part in the Freedom Summer uprising in 1964 in Mississippi. That summer, hundreds of volunteers (mostly white) traveled to the South to help blacks register to vote and to establish community centers and schools. DeBerry met Aviva Futorian ’59, a young activist. Futorian was so impressed by DeBerry’s passion for social justice and his will to pursue change that she encouraged him to apply to Brandeis.

Once at Brandeis, following a year at the Commonwealth School in Boston, DeBerry found the nurturing academic environment that Futorian had promised. The first year was a bit of a struggle, but he soon grew comfortable with the challenging academic standards.

DeBerry still recalls studying under Professors Peter Diamandopoulos, Bill Goldsmith, Morrie Schwartz (the subject of “Tuesdays with Morrie”), Maurice Stein, Ruth Morgenthau and Lawrence Fuchs. “I remember all their names because they had an impact on me,” he says. “At Brandeis, you tended to build a personal relationship with professors.”

Now retired following a career as an executive in state and local government and higher education, DeBerry continues his campaign for human rights. He serves as an adjunct professor of public policy and administration at Jackson State University and is the activist in residence at the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation at the University of Mississippi. He is also executive director of the Hill Country Project, the economic development initiative that he co-founded to create an oral history that documented the civil rights movement in Benton County, Miss. The Hill Country Project also provides educational support to local students. He is currently developing a partnership so Brandeis students can mentor Ashland High School students in math, English and science.

Like any proud graduate, DeBerry counts among his most memorable moments at Brandeis the day when his parents visited campus to watch him receive his PhD. DeBerry’s family and friends will be in attendance to see him accept the Alumni Achievement Award, too.

When asked what advice he would give today’s students, DeBerry says: “I’m not that good at giving out advice; what I do is live by example. I hope I model my life in a way that young people might want to emulate, but in the end you have to find your own voice. Whatever is in your own heart, your own mind, your own spirit, find that voice and act on it. Sometimes change has to be demanded.”