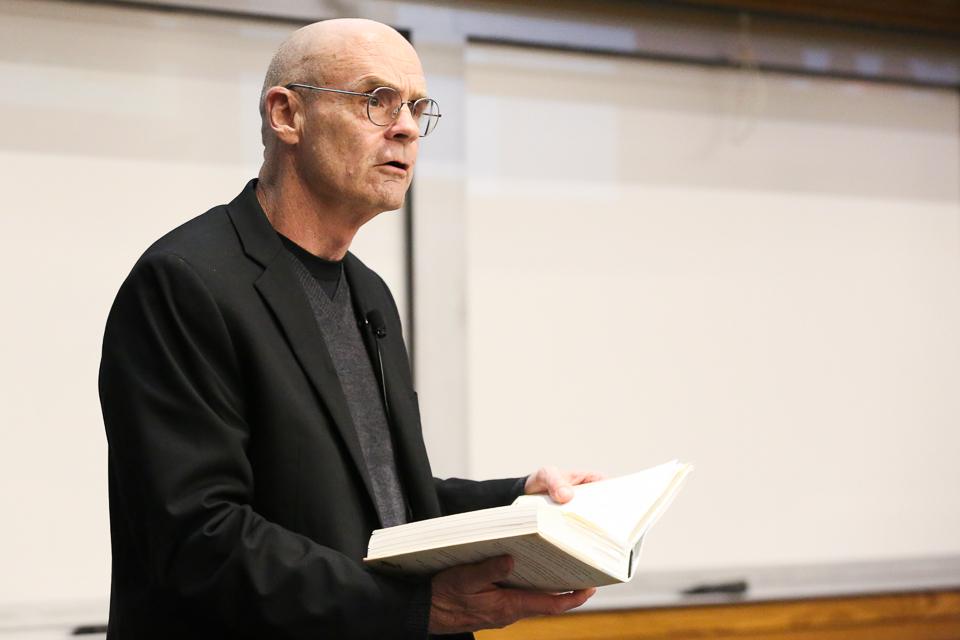

Podcast: Jack E. Davis, PhD'94, Discusses His Pulitzer Prize Winning Book, "The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea"

Photo Credit: Mike Lovett

March 21, 2019

Simon Goodacre | Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

Jack E. Davis, PhD'94, returned to campus on March 19, 2019 to give a talk about his Pulitzer Prize winning book, The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea. He sat down with us for half an hour to discuss the book, his next project on the history of the bald eagle and to provide some words of advice on how students of history can improve their own writing.

Transcript

Simon:

Hello and welcome to the Highlights Podcast. I am Simon Goodacre, the Assistant Director of Communications and Marketing for the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at Brandeis.

Today I'll be speaking with Jack E. Davis, who earned a PhD from Brandeis in 1994. Jack is a professor of history at the University of Florida and the 2018 recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for history for his book, The Gulf, the Making of an American Sea, published by Liveright/W.W. Norton. In the New York Times Book Review, Philip Connors wrote of the book, “Davis has written a beautiful homage to a neglected sea, a lyrical paean to its remaining estuaries and marshes, and a marvelous mash up of human and environmental history.”

The book was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for nonfiction, and the winner of the Kirkus prize for nonfiction, and included in the best of lists for the Washington Post, NPR, Forbes and the Tampa Bay Times.

We're excited to have you on campus this evening, Jack, and thank you very much for making time for the podcast while you're here.

Jack:

My pleasure. It's great to be back.

Simon:

I have to ask you the obvious question to start with. What were you doing when you found out that you had won the Pulitzer?

Jack:

Well, it was on campus, in my office, in a meeting with a graduate student. And I should preface that by saying, I was not aware of the Pulitzer being announced that day. I didn't even know that my book had been nominated. The finalists are not announced before the winners are announced. And so, it's completely off my radar screen. On the afternoon of April 16, in truth I was reading the riot act to this graduate student for his sloppy writing and the phone started ringing in the office, and my cell phone started exploding with texts and voicemails, and neither would stop. So, I excuse myself for a moment to turnaround and check my text messages. I saw one from my editor that said I'd won the Pulitzer and I stood up and I voiced certain words that I’ll withhold here.

And then I literally went speechless. And I had to slide the phone across the desk, to the graduate student, for him to read the text.

Simon:

Wow! I suppose when you're dealing with quotidian matters, such as a student’s sloppy writing…

Jack:

Yeah! I should add, his eyes bugged out when he read a text, and I like to say I know what he was thinking, and that was: the meeting is over.

Simon:

No more riot act today.

Jack:

Right, exactly.

Simon:

How did that paper turn out Incidentally

Jack:

It turned out really wonderful and the final was due the next week and it was quite clean and beautifully written, and so I owe it to the Pulitzer, I suppose.

Simon:

Fair enough. Before The Gulf, you had already published An Everglades Providence: Marjorie Stoneman Douglas and the American Environmental Century in 2009, and you're currently editing an edition of Wild Home of Florida, a collection of personal essays and poems about natural Florida. What is it about the state and the surrounding region that interests you so much?

Jack:

Well, I grew up in Florida and so I witnessed a lot of change in the Florida landscape, good and bad, over the years. Even though to many people Florida seems very artificial, very Disneyesque, palm trees and pastel colors. To me, there's a real sense of place there that I'm familiar with, and I like to write about a sense of place in my work.

When I was here at Brandeis, I seriously considered doing my dissertation on environmental history of the Everglades, but ultimately decided to do my dissertation on race relations in Mississippi, which became my first book.

I should also add that I'm not just editing this book on Florida. I'm also writing a new book under contract with Liveright on the cultural and natural history of the bald eagle, a bird you find not only in Florida, but all over North America.

Simon:

Yeah, actually I have a question about that later on, so, I will get back to that. On The Gulf, though, I did want to ask… The Gulf of Mexico; it's been in the news for all the wrong reasons for the last decade or so, hurricanes, the BP oil spill and so forth. What motivated you to write such a sweeping history that goes beyond the ecological disasters of the past few years?

Jack:

Well, for a couple of reasons: I felt that these disasters and all the media attention given to them had robbed the Gulf of Mexico of its true identity, and I wanted to restore that identity. The other reason is that American historians have overlooked the Gulf for the most part. And nobody has had written a comprehensive history before mine. If you look at high school and college US history textbooks, you more than likely won't find the Gulf of Mexico in the index, and if you do, it's only mentioned in passing. So, I wanted to bring the Gulf into the American historical narrative, by writing this sweeping history.

Simon:

I've heard you say in other interviews that you wanted nature to be at the forefront of this work, and the chapters of the book are organized around natural characteristics of the Gulf: estuaries, beaches, fish, birds, etc. But you also use particularly notable characters such as Rachel Carson, Ernest Hemingway in Ponce de Leon, to animate the history. How do you manage the interplay between natural and human history as you're writing?

Jack:

Yeah, that's a tricky thing. Sometimes it's also fun to try to figure out that balance and to establish those connections between the human history and the natural history. I, as you said, organize the chapters around these natural characteristics because I want nature to be in the forefront: estuaries, birds, fish, beaches, rivers, barrier islands and weather and so forth, but I recognize that my audience likes the human stories too, and I use a lot of these folks that you mentioned and other native gulf-siders to help drive the narrative. I'm telling their story as I'm also telling the story of the Gulf. And I had to pretty much learned how to do that when I wrote the Marjorie Stoneman Douglas book because the biography is really a dual biography of both Douglas herself and the Everglades.

I also have a writing partner, Cynthia Barnett, who's a fabulous environmental writer, and she does something similar. Cynthia reads everything I write and draft, and I read everything she writes and drafts, and we don't hold back punches. That’s also helpful.

Simon:

You wrote about the aborigines in the region, including the Apalachee, the Tocobaga and the Calusa. These tribes stood up to European invaders in the Gulf for up to 200 years before they were largely wiped out by disease. What first attracted Europeans to the region? And I understand that initially, the first Europeans didn't have such a good time in the Gulf even though the aboriginal population was in this bounteous location. Could you give us maybe a little potted history of that?

Jack:

Yeah, certainly. Well, of course we all have heard the story about Juan Ponce de Leon going to Florida to look for the fountain of youth, and that's a myth. His contract with the king was to sail north of Puerto Rico, look for land and find precious metals, gold or silver, and slaves. The need for slave labor really drove exploration once the Spanish came to the new world because they were wiping out the indigenous labor force that they enslaved, and they were constantly sailing off to new lands looking to replenish that labor force, and that's what brought Juan Ponce de Leon into Florida. He didn't know that the place he discovered was Florida and that it’s actually a part of a continent. He thought it was an island, and he didn't know that the Gulf of Mexico which he sailed into, was the Gulf. He wasn't sure what kind of sea it was and it was a number of years, some 15 years, before the Spanish discovered that the Gulf was the Gulf.

They met a lot of Aboriginal people who knew about the Spanish before the Spanish knew about these Aborigines because they, the Aboriginals were seafaring people, and they had a communication network that stretched across the Caribbean, The Bahamas and Yucatan. The native peoples around the Gulf of Mexico knew what the Spanish were up to and they resisted them.

The Spanish ended up encountering them everywhere they went. These native peoples were resistant and powerful, larger than they, to the point that the Spanish admired them. And not only did they have to deal with that, they had to deal with the starvation. The Spanish didn't seem to know how to feed themselves, even though they were in one of the bounteous salt water bodies in the world, which is I find is one of the great ironies. They're starving to death as they're exploring, and a number of the members of that expedition resorted to cannibalism.

Simon:

Oh, wow. I didn't know that.

Jack:

The Spanish accused the aborigines of The Gulf of Mexico, particularly that were on the Texas coast, of being cannibals. There's absolutely no truth to it.

Simon:

And jumping forward a little bit... The Deepwater Horizon incident was not the first man-made ecological disaster in the Gulf. And your book chronicles many examples of humans’ impact on the region throughout history, including our relationship with the oyster and the snowy egret populations. I was wondering, could you give listeners a primer on the impact that humans have had on those two species? I thought particularly the oyster was quite interesting because obviously we eat them but their shells have been used for other purposes as well.

Jack:

Well, when the Spanish arrived, what impressed them along with the people of the Gulf of Mexico, were the shell mounds all around the Gulf of Mexico, and these mounds—some of them were ceremonial and some were burial mounds. Whatever the case, they were indicative of the extreme wealth of the Gulf of Mexico. The Spanish encountered oyster bars or beds that went on for miles and miles and miles. And when they saw these oyster beds, they didn't see food like the aborigines did. They saw something that would destroy their ships. And ultimately, a huge toll was taken mainly on the more modern period in the late 20th century, post World War Two, on the oyster population around the Gulf of Mexico. Pollution has a great impact, engineering projects that alter the currents that destroy the estuarine environments and destroy that delicate mixture of salt and freshwater that oysters need, and the overharvesting of those beds as well.

The destruction of birdlife in the Gulf of Mexico really is the first major human impact on the Gulf of Mexico in the late 19th century. Feathered hats were all the fashion in Paris, New York, London and other places. Birds were being slaughtered by the millions around the Gulf of Mexico—and many other parts of the globe for that matter—for their feathers, and whole rookeries were being wiped out. We're talking about a rookery of 100,000 birds might be wiped out in just a matter of a few days by commercial hunters, but that devastation also launched the conservation movement in the Gulf of Mexico.

Simon:

And I understand that population has somewhat recovered. Is that correct?

Jack:

It has indeed rebounded and they are an indicator species of how well we are doing with the environment. When I was a kid growing up on Tampa Bay, about the only birds I saw were gulls and brown pelicans. I don't ever recall seeing snowy egret or a spoon bill, certainly not a bald eagle, and I'm talking in the early 1970s. The reason why I didn't see them is because that the only fish I could catch was a croaker, and, if I was really lucky, a speckled trout, because the bays were in very bad shape then into our waters of the Gulf of Mexico, mainly from wastewater pollution but also from industrial pollution. That had devastated the marine environment and the marine life. When there's no marine life, you won't have the bird life, but we've cleaned up those waters and that bird life has come back. It's really magnificent.

Simon:

You also cite the tarpon fishing particularly as having a major impact on the Gulf. Why is the fishing of tarpon such an impactful enterprise?

Jack:

Well, as I write in the book, tarpon really launched a tourist industry in in the Gulf of Mexico in the late 19th Century when a New York architect hooked the first tarpon on record with a rod and reel, and once he did, that set the sport fishing world on fire because everybody knew if you caught a tarpon then it'd be this wonderful fighting fishing, and it was is very common catch 150-175- or even a 200-pound tarpon in those days. It's an offshore fish but in the spring and the summer comes into the shore to feed, and going tarpon fishing is like going to deep sea fishing without having to go out to the deep sea. You would hook this wonderful fighting fish that would do these remarkable aerial acrobatics for 35 minutes 45 minutes and tow your two-man skiff around while doing so. You could catch a few dozen in a couple of weeks back in the late 19th Century.

That was the second major impact that the toll of the sport fishing industry took on the target population by the turn of the 19th Century. The sport fishing community recognized, and, I should say, sport fishing community—I’m talking about people coming from the northeast from the Midwest, from the British Isles to come and fish in the Gulf of Mexico—and by the turn of the century, they realized their sport was taking a toll on the population.

Simon:

Has that population rebounded at all?

Jack:

Again, taking care of the environment has been a major factor in that. Tarpon fishing is still very popular, but virtually everybody practices hook-and-release now. I should say tarpons aren't edible because they're just full of bones; they are extremely bony fish. When sports fishers were catching them, both men and women—women loved to come down on the gulf sport fish as much as men did. In fact, a woman from Kentucky held the tarpon record for seven years in the late 19th century; I think it was a 205-pound tarpon. And they would catch the tarp and have their picture taken with it, then throw it dead back in the water.

Simon:

The landscape in both the eastern and western regions of the gulf were further transformed by human intervention during the 20th Century. What have been the most significant changes and what has the ecological impact been?

Jack:

Well, the ecological impact has been similar all around the Gulf of Mexico, but the major impact as you stated has been the Southwest, Western US Gulf and the southeastern US Gulf. That is Southern Texas and Southern Florida.

The impacts have been somewhat different in Florida. It has been primarily residential development, packing in a lot of people along the shore and creating new real estate by dredging bay bottoms to make land and build a condominium on top of it, creating these very dense population centers in Southwest Florida, primarily after World War Two. Of course, that has been devastating to the estuarine environment because you have run off from storm water systems that are overtaxed, you have septic tanks that are leaky and at times during rainy season below ground water level and of course, you have runoff from the roadways, and, at this time of the year, our Snowbird season in Florida, the roadways are packed with automobiles. You have bridges and causeways connecting the barrier islands to the mainland which alter the current which have an impact on the estuarine environment.

In Southwest Taxes, the principal impact is from the petrochemical industry. If you drive down the Texas coast, it's a rare moment when you don't see a refinery for the oil and gas industry. Onshore people think that the impact of the oil industry is primarily offshore. Every day is an environmental disaster onshore because of the infrastructure that supports the offshore facilities, whether it be those refineries or whether it be shipping canals or 10,000 miles of oil industry canal slicing up the estuarine coast of the coastal marshes of Louisiana. As a consequence, those 10,000 miles of oil industry canals are contributing significantly to the erosion of Louisiana losing 25 to 30 square miles of land mass a year, along with that the Cajun culture and a generations old fishing culture.

Simon:

You mentioned earlier that you have signed a contract to write a new book, which I understand is employing the working title “A Bird of Paradox, How the Bald Eagle Save the Soul of America.” Can you give us any preview or a sneak peek to that project?

Jack:

I'd love to. Let me say why I chose to write about this bird. A couple of reasons but, one of the principal reasons was that environmental writers, such as myself, tend to write for the choir. And I don't think I did that with the Gulf book so much; I was really reaching for a broader audience. But the bald eagle is a subject that will appeal to all Americans, no matter your political background, and I wanted an environmental book that draws a politically diverse readership. Everybody loves the bald eagle whether you’re red white and blue American or you’re a tree hugger.

The other thing is that it is this wonderful success story. This comeback of the bald eagle. We nearly wiped out the bald eagle in the lower 48 states in the 1960s primarily with DDT but also with habitat destruction. But we worked very hard to bring it back and virtually every state around the country pitched in to develop restoration programs. The effort has had tremendous payout. Bald eagles are everywhere, and they are showing us… At one time scientists believed that bald eagles would not live around human population but, the bald eagles, such as the raccoon or coyotes, the bald eagles will. They are nesting on golf courses and on cul de sacs and they're showing us that we can live at peace with a wild animal and enjoy it and not diminish our quality of life. In fact, we can improve our quality of life. We've cleaned up the waters that the bald eagles depend on. It is a water bird and need it lives around freshwater or saltwater. Its primary food is fish and if those bodies of water were not clean and were not thriving with fish, bald eagles would not be around. We all drink from the same water, right? Wildlife and humans. Cleaning up those bodies of water, we've improved our own quality of life.

But also, the last thing I'll say is that the bald eagle is the founding bird. It's the symbol of the US and has been the official bird of the US since 1782. In those days, the American identity

was very much grounded in the natural endowments of North America. Nature is what distinguished America from the great European nations. We didn't have a deep history. We didn't have a nobility, and we didn't have this long heritage in America beyond native peoples of course. What we had that distinguished us from the European nations were these natural endowments, and lording over all of that, of course, was the bald eagle.

Simon:

You know, I remember when I moved to the States almost 20 years ago. The first year I was here, I visited Dollywood in Tennessee, and they have bald eagles. They have a lot of injured bald eagles there, and they did a whole bird show. And I remember the final bird, of course, that they bring out at the very end was a bald eagle, and the place just erupted. The audience went completely crazy.

Jack:

It's really remarkable. Wherever I give talks on the Gulf of Mexico, when I mention that I'm writing this book on the bald eagle, I get this collective sigh from the audience and people come up to me afterwards. Everybody has a bald eagle story. Everybody loves the bald eagles now.

Simon:

Well, there's my bald eagle story. Not the most thrilling probably, but there it is.

My final question for you: I've read so many reviews of your book and everyone comments on the quality of the writing and your ability to capture and hold the attention of the reader throughout. I was wondering if you have any tips for our budding historians about how to make their own writing more compelling?

Jack:

Well, I was fortunate that when I was here at Brandeis, I had some professors who were model writers like Christine Harriman, Jacqueline Jones, who was my dissertation advisor, David Hackett Fisher, who trained me in environmental history and, of course, a Pulitzer Prize Winner—and Mickey Keller. They all demanded good writing, and they all offered examples of good writing. And they were inspiring.

So, my tips are to surround yourself, if you can by people like that. Find yourself a writing partner as I did in Cynthia Barnett. Read good writing. Find the writing that you like, read it, emulate it, write it down, study it as you're reading it. Write down words you like, write down phrases you like, and find places to use them and, of course, developing writing skills is like developing musical skills: it requires practice, practice and practice.

Simon:

Well, once again, the book is The Gulf: the Making of an American Sea, published by Liveright/W.W. Norton. Jack, thanks again for making time for our podcast and I look forward to hearing your talk this evening. And to our listeners, I hope you'll join us next time on the Highlights Podcast.