Vivek Vimal's Rotating World

June 18, 2015

By Leah Burrows | BrandeisNow

It’s Vivekanand Vimal’s job to turn the world upside down.

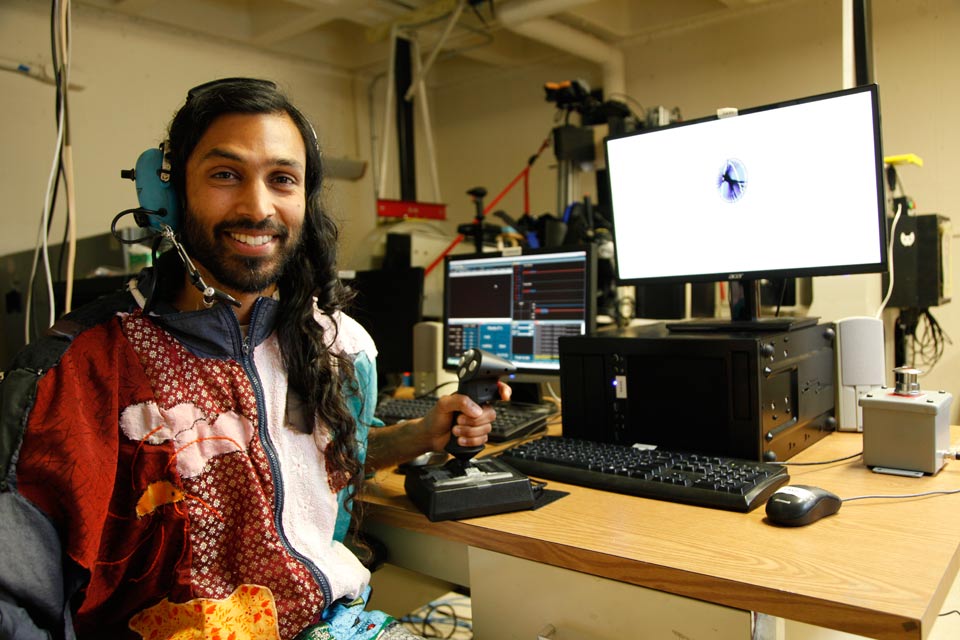

Vimal, a PhD student in the Ashton Graybiel Spatial Orientation Lab, studies how humans learn to balance when normal gravitational cues are altered. He blindfolds volunteers, straps them into a lumbering machine — nicknamed “the Hulk” — and spins them up and down, back and forth, left and right.

It may sound and look like a medieval torture device, but Vimal is collecting valuable data about how the brain responds, learns and adapts without gravitational clues. It’s important research for long-term space travel.

It’s also a metaphor for Vimal’s life.

Vimal has spent his life turning his own world upside down and sideways.

“When things are very peaceful you begin to stagnate,” Vimal says. “In moments of turbulence there is an elegant and chaotic beauty and in that flurry, you grow and develop.”

Vimal is sharing those lessons with young people as part of an outreach program he created that connects Waltham high school students with Brandeis scientists and lab research. In 2012, Vimal developed a summer internship for students interested in science and research. This winter, Vimal, Anique Olivier-Mason, director of education, outreach and diversity at Brandeis MRSEC, and Marisa Maddox, a biology teacher at Waltham high school, launched a series of lunchtime talks at Waltham high with Brandeis University graduate students and postdocs.

“I want to show students that they can be creative and produce something really beautiful and amazing even if they don’t have the best grades,” Vimal says.

Growing up in Lexington, Mass., Vimal had bad grades and would spend hours daydreaming instead of doing homework.

“I felt like I wasn’t smart and like I couldn’t do anything to change who I was,” he says.

In college, however, Vimal upended that idea. The student who barely scrapped by in high school majored in physics and minored in mathematics and computer science at Boston University. The kid who never played sports joined the Marine Corps’ Officer Candidates School.

Vimal spent two summers testing his endurance with 12-mile hikes in full combat gear, tackling obstacle courses and conditioning himself for combat. The intensity and physical challenge gave Vimal more confidence and a greater sense of self.

“It really helped develop who I turned out to be,” he says.

After graduating, Vimal was offered a commission of second lieutenant but decided to take another path — it was time to look at the world differently.

He let his hair grow out and promised himself that he wouldn’t cut it until he felt he had made a difference in the world. What skills would he need to make that difference? First, he would need to overcome his fear of public speaking.

He applied for a teaching position at Waltham High School. He says he was nervous everyday over the next two years he walked into the classroom to teach physics. Despite his growing locks and eccentric teaching style, Vimal was accepted in the Waltham community.

“The community allowed me to be myself and express myself,” Vimal says. “I was able to bloom, try out my own labs, bring in my guitar.”

And, for six years, Vimal (and his hair) grew.

Then, it was time to look at the world differently.

Vimal took a leave of absence, shaved his head and moved to India to work for an a non-government organization. He made documentary films about climate change and child welfare, wrote grants, and traveled around the country.

When he returned to Waltham, he decided to go to graduate school. As a teacher at Waltham High, Vimal had taken classes at Brandeis and became intrigued with neuroscience.

“Science is both grounding and romantic to me,” Vimal says. “Science has this mathematical backbone but, through discovery, you can experience something that no human has ever experienced or known before. It’s breathtaking.”

Vimal completes his PhD next year. After that — who knows?

“I always tell my students, you don’t have to have a clear trajectory in your life. I certainly didn’t,” Vimal says. “You just have to have the desire to push yourself, and, like Lego pieces, you can construct your own world.”