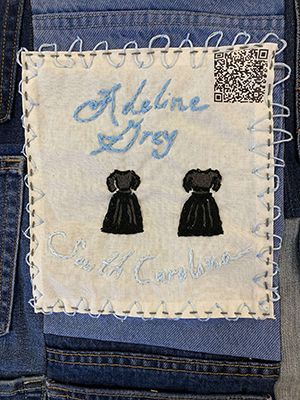

Adeline Grey

“I was a girl when freedom was declared. My Ma used to belong to old man Dave Warner. I remember how she used to wash, and iron, and cook for the white folks during slavery time. I used to weave cloth after freedom. I used to give a brooch (hank) or two to weave at night. I’d sometimes thread the needle for my Ma, or pick out the seed out the cotton, and make it into rolls to spin. Sometimes I'd work the foot pedal for my Ma, then they'd warp the thread. If she wanted to dye it, she'd dye it. She'd get indigo - you know that bush - and boil it. It was kind of blue. It would make good cloth. Sometimes, the cloth was kind of striped, one stripe of white, and one of blue. I remember how they'd warp the thread across the yard after it was dyed, and I remember seeing my Ma throw that shuttle through and weave that cloth. I remember when the old Miss made my Mamma two black dresses to wear through the winter. She'd keep them clean; had two so she could change. I never did know my Pa. He was sold off to Texas when I was young. My father was named Charles Smart. He never did come back. Joe Smart came back once, and said that our father is dead.” – Adeline Grey

David Zavala ’26

David Zavala ’26

Slave Traders first kidnapped people in Africa then stripped them of all clothing, removing any personal dignity or personal identity. If they endured the trans-Atlantic voyage, they were then sold on a block, also while naked. Once purchased, the plantation owners clothed them according to rank. House servants were allotted linen and finer clothing, while field workers were issued coarse “slave cloth”. Each Plantation kept records called “blanket books” of how many textiles were assigned to each enslaved worker, usually two outfits, twice a year. But this was not always the rule. George Washington doled out annually to his enslaved men “one wool jacket, one pair of wool breeches, two linen shirts, one or two pair of stockings, one pair of shoes, and linen breeches for summer”. While the women at Mount Vernon received “one wool jacket, one wool skirt, two linen shifts, one pair of stockings, one pair of shoes, and a linen skirt for summer”. The workers often spun, wove, and sewed the garments that were “given” to them. After a year of hard manual labor, this clothing would often be tattered, when the women then recycled any usable pieces into quilts or patches for other clothing.

“Black Codes” were laws that restricted clothing given to enslaved workers so they could be identified easily. Many advertisements describing runaway slaves note that they were not wearing their officially issued clothes. Like a striped prison uniform, these garments were easily identifiable. In her memoir, formerly enslaved worker Harriet Jacobs described how dressing in this made her feel: “I have a vivid recollection of the linsey-woolsey dress given me every winter by Mrs. Flint. How I hated it! It was one of the badges of slavery”. Trying to control African-Americans’ choices on personal appearance continues to this day. In 2019, in response to workers and school children being punished due to their hair, the CROWN Act was created “to ensure protection against discrimination based on race-based hairstyles by extending statutory protection to hair texture and protective styles such as braids, locs, twists, and knots in the workplace and public schools.” As of 2023, 24 states have now adopted the CROWN Act into their anti-discrimination guidelines.

Sources

- Federal Writers' Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 14, South Carolina, Part 2, Eddington-Hunter. 1936. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Federal Writers' Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 14, South Carolina, Part 2, Eddington-Hunter | Library of Congress.

- Clothing the Black Body in Slavery: What They Wore and How it Was Made.

- “Slave Cloth” | EnCompass

- CROWN Act

- Overview of CROWN (Create a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair) Act Legislation - Online CLE Course | Lawline

- Slave Cloth and Clothing Slaves: Craftsmanship, Commerce, and Industry | The MESDA Journal