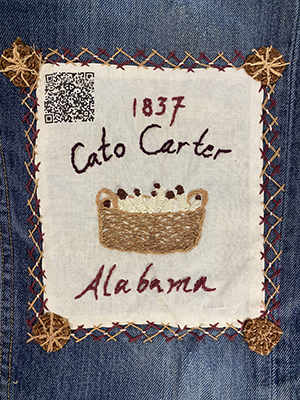

Cato Carter

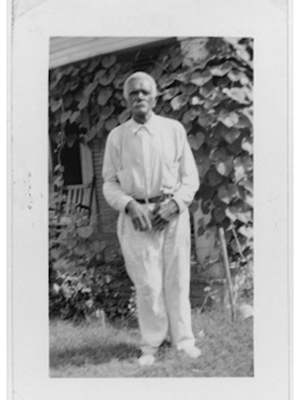

“I been going every day on the truck to the cotton patches. I don't pick no more, on account my hands get too tired and begin to cramp on me. But I go and set in the field and watch the lunches for the other hands. I am a hundred one years old, because I was twenty-eight when the breaking up come. I'm pretty old, but my old, black mammy, Zenie Carter, lived to be a hundred twenty-five, and Oll Carter, my white master - which was the brother of my daddy - lived to be a hundred four. Al Carter, my own daddy, lived to be very ageable, but I don't know when he died. Back in Alabama, Missie Adeline Carter took me when I was past my creepin' days to live in the big house with the white folks. I had a room built on the big house, where I stayed, and they was always good to me, because I was one of their blood. There was lots of deer and bears and quails and every other kind of game, but when they ran the Indians out of the country, the game just followed the Indians. My grandmamay’s daddy was a Choctaw Indian. I used to tend the nursling thread. The reason they called it that was when the mammas was confined with babies having to suck, they had to spin. I'd take them the thread and bring it back to the house when it was spinned. If they didn't spin seven or eight cuts a day they'd get a whupping. It was considerable hard on a woman when she had a frettin’ baby. The Carters said a hundred times they regretted they never learned me to read or write, and they said my daddy done put up $500.00 for me to go to the New Allison school for colored folks. I was twenty-nine years old and just' starting in the blueback speller. I went to school a while, but one morning at ten o’ clock my poor old mammy come by and called me out. She told me she got put out, because she too old to work in the field. I told her not to worry, that I'm the family man. So I left school and turned my hand to anything I could find for years.” – Cato Carter

Lev Sewald ’26

Lev Sewald ’26

The Alabama Slave Code of 1833 states: “Any person who shall attempt to teach any free person of color, or slave, to spell, read or write, shall upon conviction thereof by indictment, be fined in a sum of not less than two hundred fifty dollars” Most of the Southern states passed similar anti-literacy laws, fearing that if their enslaved workers could read and write, they would not only organize and riot, but they would tell their stories to the world. In Maryland, after discovering his wife was teaching a young Frederick Douglass how to read, Slave owner Hugh Auld berated her by saying: “He should know nothing but the will of his master and learn to obey it. As to himself, learning will do him no good, but a great deal of harm, making him disconsolate and unhappy. If you teach him how to read, he’ll want to know how to write, and this accomplished, he’ll be running away with himself.” Later in his life, Douglass purchased land in Maryland and built a school there. Addressing the students in 1883 he described his own education to them: “That boy did not wear pants like you do, but a tow linen shirt. Schools were unknown to him, and he learned to spell from an old Webster's spelling-book and to read and write from posters on cellar and barn doors…He would then preach and speak, and soon became well known. He became Presidential Elector, United States Marshal, United States Recorder, United States diplomat, and accumulated some wealth. He wore broadcloth and didn't have to divide crumbs with the dogs under the table. That boy was Frederick Douglass”

After it became legal in the US to educate all children equitably, systemically racist segregation laws were enacted to separate children based on the color of their skin in schools. Even after the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case outlawed segregation in schools in 1954, students today do not receive an equal education. Because the US public school system is financed based on property taxes, wealthy white suburban schools spend more per student than those in impoverished areas. To counteract this inequity, inspired by the civil right movement, Public Television began broadcasting educational shows specifically aimed at raising literacy in young inner city children. Beginning in 1969 with Sesame Street and continuing with LeVar Burton’s Reading Rainbow in 1983, these shows made learning accessible, relatable, and fun for all kids.

Sources

- Federal Writers' Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 16, Texas, Part 1, Adams-Duhon. 1936. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Federal Writers' Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 16, Texas, Part 1, Adams-Duhon | Library of Congress.

- Literacy By Any Means Necessary: The History of Anti-Literacy Laws in the U.S – Oakland Literacy Coalition

- How We Got to Sesame Street | The New Yorker