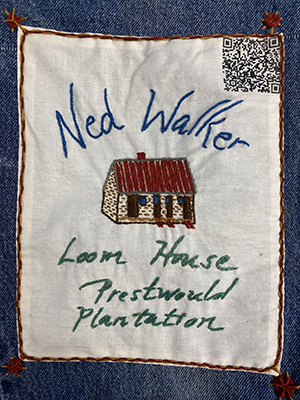

Ned Walker

“The day I was born, I belonged to my master, David Gaillard. After the war he fixed it so the slaves stayed together on that 1,385 acres and buy the place, as common tenants on the installment plan. He sent word for the head of each family to come to Winnsboro…to have names and register. My daddy already had his name, Tom. He was the driver of the buggy, the carriage, and one of the wagons, in slavery. Master Henry wrote him a name on a slip and said: “Tom, as you have never walked much, I name you Walker.” My mammy’s named Bess, my granddaddy named June, grandmammy, Ronah. But all my brothers are dead. My sisters Clerissie and Phibbie are still living. We were bom in a two-story frame house, chimney in the middle, four rooms down stairs and four up stairs. There were four families living in it. There was a big hall with spinning wheels in it, where the thread was spun. That thread was hauled to Winnsboro and brought to the Clifton Place, to the weaving house. Mammy was head of the weaving house force, and saw to the cloth. ” – Ned Walker

E. Azua ’26

E. Azua ’26

In India’s modern textile industry, slavery is wrapped in the allure of providing your own dowry. Recruiters target low caste young girls with a promise of three meals a day, satellite TV, and heaps dowry money if they leave school to work in a textile mill for three years.

To 16-year-old Vasandi, it sounded like heaven and a responsible way to earn money for her family. She moved from her small rural town into a dorm that she would share with 320 other women where the warden bolted the door each night from the outside. She learned to run skeins of cotton thread on to a giant spindle, and to clean cotton fibers off machinery to keep it running smoothly. Vasandi worked at one of the hundreds of mills that spin cotton for textile factories that supply European and North American retail chains like H&M, Abercrombie & Fitch, and the Gap. There was a TV in the dorm, but she was usually too tired after her 12-hour shift to watch.

Even though she was earning $50 a month, she had no idea that what she was doing was illegal. Like her, the majority of the mill workers were under 18, with a fifth of them younger than 14. Indian law requires minors to be in school. She was underpaid, earning less than half of minimum wage for apprentice textile workers, 196 rupees ($4) a day.

Also unknown to Vasandi was that the money for her promised dowry was being deducted from her wages, making her a bonded laborer, which has been illegal in India since 1976. (Dowry practices and the caste system were also supposed to be illegal but never enforced.) During her two years working there, she had only ever seen six girls out of some 600 receive their bonuses. Most were injured and left or quit first. Girls close to the three-year mark would often randomly be fired. Several NGOs are doing their best to help eradicate bonded labor in India, but with the textile and garment factories being the second largest employer in the country with over 45 million workers, it’s hard to regulate.

Sources

- Federal Writers' Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 14, South Carolina, Part 4, Raines-Young. 1936.

- “In parts of India, dowry schemes are used to lure girls to bonded labour “- The Globe and Mail