Susan McIntosh

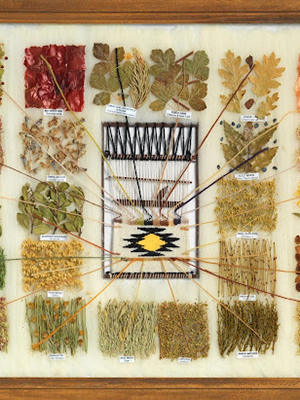

“They tell me I was born in November 1851 and I know I’ve been here a long time because I've seen so many come and go. I've outlived almost all my folks, except my son that I live with now. Ma's name was Mary Jen, and Pa was Christopher Harris. Master Young L. G. Harris bought him from Master Hudson. Pa was coachman and house boy for Miss Lula. Master Billy owned Ma, and Master Robert owned Pa, and he came to see Ma about once or twice a month. There were thirteen of us children, but seven died soon after they were born, and none of them lived to get grown except me. Their names were Nanette and Susan - that’s me- Isabelle, Martha, Mary, Diana, Lila, William, Gus, and the twins (who were born dead) and Harden. He was named for a Dr. Harden who lived here then. Master Billy bought my grandma in Virginia. She was part Indian. I can see her long, straight, black hair now, and when she died she didn't have gray hair like mine. Grandma made cloth for the white folks and slaves on the plantation. I used to hand her thread while she was weaving. My aunt, Mila Jackson, made all the thread that they did the weaving with. In summer, the slave women wore white homespun and the men wore pants and shirts made out of cloth that looked like overall cloth does now. In winter, we wore the same things, except Master Billy gave the men woolen coats that came down to their knees, and the women wore warm wraps, what they called sacks. On Sunday we had dresses dyed different colors. The dyes were made from red clay and barks. Bark from pines, sweetgums, and blackjacks was boiled, and each one made a different color dye.” – Susan McIntosh

Ofri Levinson ’25

Ofri Levinson ’25

For centuries before European colonizers arrived, Native Americans harvested tree barks to use as dyes and medicines. Some indigenous people, perhaps like Susan’s grandma, shared their knowledge of natural chemistry with the newcomers. Respecting the land and using local natural resources meant that our planets’ ecosystem remained fairly stable until the onslaught of carbon emissions in the 20th century. Using natural materials to dye almost disappeared as a part of common knowledge because of one teenager’s experiment gone wrong. In 1856 17 year old chemistry student William Henry Perkin was spending his Easter break from London’s Royal College of Chemistry conducting experiments in a lab he fashioned in his parents’ attic. What he was trying to make was an anti-malaria medicine, but what he discovered was the world’s first synthetic dye. By the next year he was opening his own factory to create vibrant purple dyed cloth for the world. Soon, scientists around the world had figured out how to synthesize the whole rainbow of colors from coal tar and the entire indigo and natural dye market collapsed. Although the new aniline dyes were more bright and lasted longer, their production polluted the air and water horribly. Fortunately, sustainably grown indigo companies like Harvest & Mill and Stony Creek Colors are making a comeback as consumers become more aware of where and how their clothing is made.

Sources

- Federal Writers' Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 4, Georgia, Part 3, Kendricks-Styles.

- Native Plant Dyes, usda.gov

- Native American Ethnobotany Database

Sir William Henry Perkin | Science Museum Group Collection - The American-Grown Indigo Collection – Harvestandmill.com