What Can Chimpanzees Teach Us about Care?

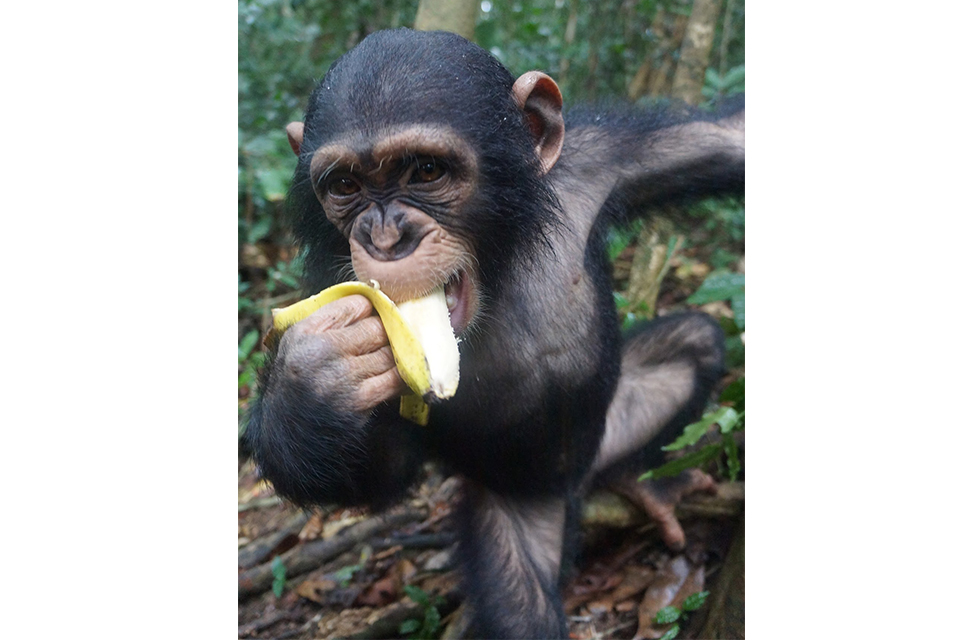

Photo Credit: Karena Tilt

November 15, 2018

Simon Goodacre | Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

Listen to the podcast or read the transcript of an interview with Amy Hanes where she discusses her dissertation, caring for chimpanzees in Cameroon, and the Newcombe Fellowship.

The first night Amy Hanes, MA’11, PhD’19, spent in the Sanaga-Yong sanctuary for orphaned chimpanzees in Cameroon was a memorable one. She knew it was deep in the Mbargue Forest with no electricity or running water.

“I could handle rural. I did rural in the Peace Corps. However, I had never done rural in a Central African forest,” she says. After a seven-hour train ride from Yaoundé, the capital, she arrived at the train station in Belabo at about 2:00 in the morning, where a driver was waiting for her. They drove for over an hour into the forest.

Finally, at the Sanaga-Yong Chimpanzee Rescue, their destination, Amy spent an hour fumbling in the dark in a small cabin, trying to find a change of clothes, bug spray and sheets. She finally managed to set up her mosquito net. “When I laid down, sweaty, tired and hungry, something screamed. It was a pig’s squeal, a hawk’s screech and a human’s scream all melded together. I remember saying out loud to no one in particular, ‘Are you SERIOUS?’ I nicknamed whatever made the noise ‘murder bird.’” (Amy learned later that the screamer was a hyrax — a small mammal that looks like a husky guinea pig.)

Once murder bird stopped, the chimps started. Their screams were louder, longer and more terrifying than murder bird’s. It was clear they were coming, probably an entire troop. Amy said, “I reviewed my options. The lock on my cabin door was something a chimp (or I) could easily snap in two. I did not know if any other humans were nearby and I was pretty sure that if I used the head torch it would lead them to me, so I just lay there.”

The next day, Amy — playing it cool — asked a caregiver if any chimps had escaped the night before. He laughed and explained that, like humans, chimps cannot see in the dark. He said one chimp probably rolled over onto someone else who was asleep. Night fights can turn into mayhem, but eventually everyone settles down. “It was the first of many times that I asked myself, ‘What in the hell have I done?’” Hanes says.

By the time Hanes landed in Cameroon in 2013, on the first of several trips to the sanctuary, she already had a dual master’s degree in sustainable international development and women’s and gender studies. Now she was pursuing a doctorate in anthropology at Brandeis, the natural outcome of a Peace Corps stint years earlier in Niger. While there, she spoke Djerma (a Nigerian language) and worked on education-based projects with a strong gender component in the small town where she lived. Over time, she came to the view that many, if not most, development organizations were failing to make lasting change.

Hanes realized that she did not want to work in development — she wanted to question it. “I chose anthropology as a discipline because of its methods. Whether we study human-chimp relationships, violence in prison, or love in a virtual world, we gather data by participating in whatever it is we want to understand,” she says. “Diving into my questions anthropologically has shown me things about the world that I would never otherwise see.”

Hanes’ dissertation explores “care.” She is interested in how people of different nationalities, religions, economic means, and education levels all grapple with how to define and provide care across species lines. (For more information about Amy's dissertation, listen to the podcast at the top of this page.)

During her first research trip to Cameroon, she volunteered at a small, urban wildlife sanctuary. “I quickly noticed that the word ‘care’ crept up constantly in peoples’ conversations, debates and arguments,” she says. “Some declared their devotion to a cause and its attendant values when they said things like ‘I care about wildlife conservation.’ People tried to shape each other’s behavior by claiming, ‘If you cared about us you would treat us better.’

Hanes says care became racialized when Cameroonians asked, ‘Do whites care more about wildlife than about us?’ or when Westerners asked, ‘Do Cameroonian staff care more about their salaries than the animals?’

During her time in Cameroon, Amy cared for infant chimpanzees. People ask her what it is like to care for them. Since chimps seem to have different personalities, she usually uses a single chimp as an example, “Caring for a one-year-old female infant named Gnala, was like being responsible for a human toddler hyped up on Mountain Dew and chocolate, who could run faster, climb higher, and bite harder than you,” Hanes says. However, the connection that grew between her and her charge was significant. “Sometimes I sat in disbelief — we were two great apes who, using chimp vocalizations and gestures, could communicate with one another.”

The chimps in these sanctuaries are orphaned. Many were kept as pets, others were displayed at hotels to entertain guests, and some were starved, confined to boxes or bags until a trafficker could find a buyer. “Most days, usually in the afternoon, I sat back and remembered that I was not supposed to be there,” says Hanes. “I was not supposed to know Gnala’s favorite fruit or which areas of the forest she liked to explore. I was not supposed to know how to groom a chimpanzee. We were not supposed to be together. She was supposed to be with her mom, and that made it all deeply sad.”

Since the sanctuary was short staffed and infant chimps need 24-hour care, Amy became the primary caregiver for a nine-month-old male chimpanzee named Little Larry. “For two months we were together 22 hours a day,” she says. At night the infant chimp slept on a small mattress next to her bed, and they spent their days in the forest with two other orphans, a two-year-old female named Daphne, and a one-year-old female named Paula.

“When you are together for that long you develop rhythms,” says Hanes. “I knew Little Larry’s proportions and how he preferred to be carried. He battled the other infants for sugar cane, then came to me for reassurance when he lost. I sat nearby when he wanted to play alone, and he hit me in the back of the head when he wanted to be chased.”

Two months later Little Larry transitioned to a fulltime Cameroonian caregiver, and Hanes rotated in to do daytime forest shifts with the three infants. “Leaving him was one of the hardest things I have had to do,” she says. The Cameroonians called her “la mère de Little Larry,” or “Little Larry’s mother.”

“I had heard them do this with other caregivers, but it was startling when they did it for me,” she says. “It gave me pause and made me question who I was to him.”

When her fieldwork ended in 2016, Amy considered staying. She knew Little Larry would soon transition from human care to an all chimp group where he would be the youngest and smallest. “Even if I did to see him through his transition, we would still have to part ways,” she says. “I was not his mother. I was his human.”