A Tale of Two Converts

June 10, 2016

By Lisa Fishbayn Joffe

Editor’s note: This blog has been updated from one that originally ran June 10, 2016.

This is the story of two converts to Judaism. Their stories take place several millennia apart. One story is told in the Book of Ruth, which Jewish congregations read during the coming festival of Shavuot. The other is from the present day. The contrast between them illustrates the ambivalent welcome converts to Judaism may receive in Israel today.

We begin with the story of Ruth. There was a famine in Israel. Two Jews, Elimelech and Naomi, migrated with their two sons to Moab. Elimelech died and the sons married Moabite women. After ten years, both of Naomi's sons died, too. She turned to her now widowed daughters in law — Orpah (for whom Oprah Winfrey was supposedly named, but for a county clerk with poor spelling) and Ruth, and tells them that she intends to return to her people in Israel. Naomi urges them to go back to their own Moabite families.

Initially, they both resist and want to come with her, but she insists that they go back to their own tribes to find new husbands. Orpah agrees and bids her mother-in-law and tearful goodbye. Ruth, however, refuses to go.

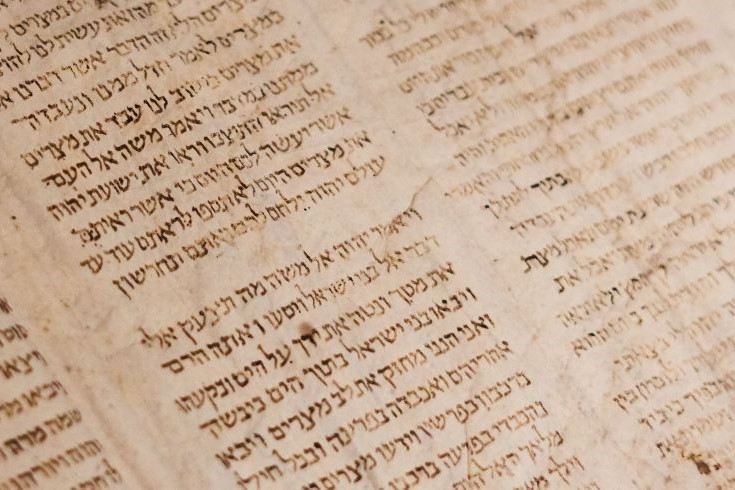

"And Ruth said: 'Entreat me not to leave you, or to return from following after you. Wherever you go, I will go; and where you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your G–d my G‑d. Where you die, I will die, and there will I be buried; G‑d do so to me, and more also, if aught but death part you and me.' "

"And Ruth said: 'Entreat me not to leave you, or to return from following after you. Wherever you go, I will go; and where you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your G–d my G‑d. Where you die, I will die, and there will I be buried; G‑d do so to me, and more also, if aught but death part you and me.' "

As a girl, I always loved the story of Ruth. I saw it as a wonderful vision of loyalty and friendship. I see now that it is also one of the few stories in the Tanakh that passes the Bechdel test. This metric was developed by the cartoonist Alison Bechdel, to identify films that treat women’s experience as important. To pass the Bechdel test, a story must have:

- at least two women;

- who have names, (rather than wife of X or daughter of X);

- who have a substantial conversation with each other;

- about a topic other than a man.

Bechdel in turn gives credit for her test to the work of Virginia Wolf, in "A Room of One's Own," where Wolf writes of being startled when reading a novel to come across these words. "Chloe liked Olivia."

"Chloe liked Olivia... " Do not start. Do not blush. Let us admit in the privacy of our own society that these things sometimes happen. Sometimes women do like women.

"Chloe liked Olivia," I read. And then it struck me how immense a change was there. Chloe liked Olivia perhaps for the first time in literature. ... All these relationships between women, I thought, rapidly recalling the splendid gallery of fictitious women, are too simple. So much has been left out, unattempted. And I tried to remember any case in the course of my reading where two women are represented as friends."

Ruth is not just a model of a woman capable of friendship with another woman. She is also the cited as the first explicit example of a convert who makes a conscious choice to join the Jewish people — to make our people her people and to make our G-d, her G-d.

How does she do this? She does not have to take a course, learn a set of rules, pass a test, immerse in the mikveh or get a seal of approval from a rabbinical court. She just makes a conscious decision to throw her lot in with the Jewish people — and she is welcomed with open arms. She becomes not only a beloved member of the community but an important part of the development of our story. Ruth, we later learn, is the great grandmother of King David. Without her, Jewish history might have been very different. Or perhaps her conversion to Judaism was something G-d had planned all along.

Our second story is that of Sarit Azoulay, a young woman now living in the modern State of Israel. She was born and raised as a Jew, served in the army and is a citizen of the state. In 2012, she went to register for a marriage license with the Israeli marriage registrar. There is no civil marriage or divorce in Israel. One who identifies as a Jew can only be married by a state recognized Orthodox Jewish rabbi. Azoulay's identity documents showed that her mother had converted to Judaism some 30 years before under the auspices of Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Israel, Shlomo Goren. These documents are part of a national registry that shows the religious and ethnic identity of all Israelis.

Instead of granting the license, and wishing her well on her wedding, the registrar told her of new regulations that had recently been introduced that required an inquiry "to clarify her Jewishness." Her case was referred to a "Jewishness investigator" appointed by the state. A rabbinic court summoned Azoulay’s mother to attend and answer questions about her lifestyle regarding her knowledge and practices. While she celebrates the holidays and observe kashrut, she confessed that she is not shomer Shabbat. The rabbinical court found her wanting and told her daughter she was not eligible to marry in Israel because her mother’s conversion was invalid. Azoulay's name was placed on the Prohibited Marriages list, a list that includes several thousand Jewish Israelis, half of whom are on there because of suspicions about the validity of their conversion or that of their mothers or grandmothers.

In Azoulay's case, she was able to marry through the benevolence of a sympathetic Orthodox rabbi who registered her for marriage as the municipal rabbi of Shoham. However the rabbinical court ruling discrediting her conversion still stood. She became a mother and worried that the aspersions cast on her Jewishness would be passed on her little girl when she sought to marry someday. With the help of Susan Weiss at the Centre for Women's Justice, Azoulay appealed the rabbinical court decision in 2015.

"No convert can sleep peacefully in Israel," Weiss told Ha’aretz. "All converts at any time can find themselves hauled into a Haredi-controlled state rabbinical court" and "interrogated about their lifestyle, and sometimes the conversion can be declared invalid. Now we see added to this circle the children of converts who were born and raised completely Jewish."

The decision in Azoulay's case was overturned in April 2016 by the Supreme Rabbinical Court. They held that it was not proper to retroactively invalidate a conversion. Once a Jew was accepted into the fold, they were Jewish for good or ill and this could not be reversed. But they cautioned that this made it all the more important to have effective Jewishness inspection at the time of conversion. In fact, they affirmed the procedure for investigating the Jewishness of any converts or children of converts who sought marriage licenses.

A recent report from the Israeli Prime Minister's Office shows that the number of conversions administered by state authorities in Israel declined by 30% between 2014-18. While many people begin the process, the number who are able to complete it has declined from 60% to 29%. Critics say this is because the state rabbinical courts demand that converts will adhere to Orthodox interpretations of Jewish law, thereby excluding those who wish to ally themselves with more liberal denominations within Judaism. A pluralistic state needs to recognize the plurality of forms of religious conversion in order to accommodate the religious practices of Jews from around the world.

Ruth, our first righteous convert, did not have to go before an ancient version of the Jewishness inspector. One looks forward to a day when modern converts will be offered as warm a welcome.

Lisa Fishbayn Joffe is the Shulamit Reinharz Director of HBI. She is also director of the HBI Project on Gender, Culture, Religion and the Law and affiliated faculty in the Brandeis Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies.

Lisa Fishbayn Joffe is the Shulamit Reinharz Director of HBI. She is also director of the HBI Project on Gender, Culture, Religion and the Law and affiliated faculty in the Brandeis Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies.

For more on Shavuot and the Book of Ruth, read " Shavuot Is About A Poor Convert — Would Your Community Welcome Her Today?" by Sharon Weiss-Greenberg, director of development and communications for ELI Talks and director of donor relations at RAISE Advisors. Before making aliyah to Israel with her family, she served as the executive director of JOFA.