Gender, Politics, and Jewish Star Bodies in U.S. Pop Culture

Jonathan Branfman, Ph.D.

Long seen as an internal Jewish concern, antisemitism has surged to national attention in America since Hamas’s October 7, 2023 attack on Israel, Israel’s subsequent invasion of Gaza, and the ensuing mass pro-Palestinian protests on US college campuses. As some of these demonstrations have crossed into antisemitic harassment and violence against Jewish students, antisemitism has become a regular topic in headlines, Congressional hearings, and everyday conversations. These events have also sparked national debate about which criticisms of Israel qualify as antisemitic, a question previously limited to academic, activist, and Jewish circles.1 Further, Republican politicians have cited campus antisemitism to justify sweeping efforts to defund and censor universities, and to deny the due process rights of activists and foreign students.2 In turn, some American Jews have publicly warned that these measures exploit real concerns about antisemitism to wrongfully erode higher education, free speech, and civil liberties for all Americans.3

Long seen as an internal Jewish concern, antisemitism has surged to national attention in America since Hamas’s October 7, 2023 attack on Israel, Israel’s subsequent invasion of Gaza, and the ensuing mass pro-Palestinian protests on US college campuses. As some of these demonstrations have crossed into antisemitic harassment and violence against Jewish students, antisemitism has become a regular topic in headlines, Congressional hearings, and everyday conversations. These events have also sparked national debate about which criticisms of Israel qualify as antisemitic, a question previously limited to academic, activist, and Jewish circles.1 Further, Republican politicians have cited campus antisemitism to justify sweeping efforts to defund and censor universities, and to deny the due process rights of activists and foreign students.2 In turn, some American Jews have publicly warned that these measures exploit real concerns about antisemitism to wrongfully erode higher education, free speech, and civil liberties for all Americans.3

Although antisemitism and Jewish identity rarely receive such explicit attention in national news media, these themes do more tacitly infuse everyday American popular media. Across films, TV series, music videos, webisodes, comedy clips, and other media, audiences regularly consume storylines and jokes built on implicit assumptions about Jews—for instance, assumptions about how Jews allegedly look, speak, move, think, and lust. And whether coming off as pejorative, benign, or too subtle to consciously notice, these assumptions descend from a multi-century arc of antisemitic tropes in literature, theater, art, theology, and pseudoscience. That is not to say that today’s pop cultural images always promote negative or dismissive thinking about Jews, although some certainly do. Rather, these images illuminate how a long tradition of antisemitism continues to inform everyday American “common sense” about appearance, conduct, and speech, even for audiences who hold no malice toward Jews, and even for many American Jews themselves.

Take, for example, the hit animated children’s film Madagascar (2005), whose cast of talking animals includes the hypochondriac giraffe Melman Mankowitz, voiced by Jewish actor David Schwimmer. Melman’s Jewish name and neurotic antics tap into familiar tropes of Jewish men as anxious and frail. And although rendered lightheartedly in Madagascar, these tropes descend from at least eight centuries of stigmas portraying Jewish men as weak or emasculated—sometimes even menstruating—in contrast to ostensibly more masculinized white Christian men.4 In the 18th century, for example, such beliefs shaped legal debates in Europe over whether Jewish men were masculine enough to serve in the military, and thus eligible for equal rights.5 In turn, such stigmas about Jewish masculinity form one thread in a broader lineage of antisemitic stigmas about every aspect of Jewish men’s and women’s minds and bodies, stigmas that continue to casually weave through pop cultural entertainments like Madagascar.

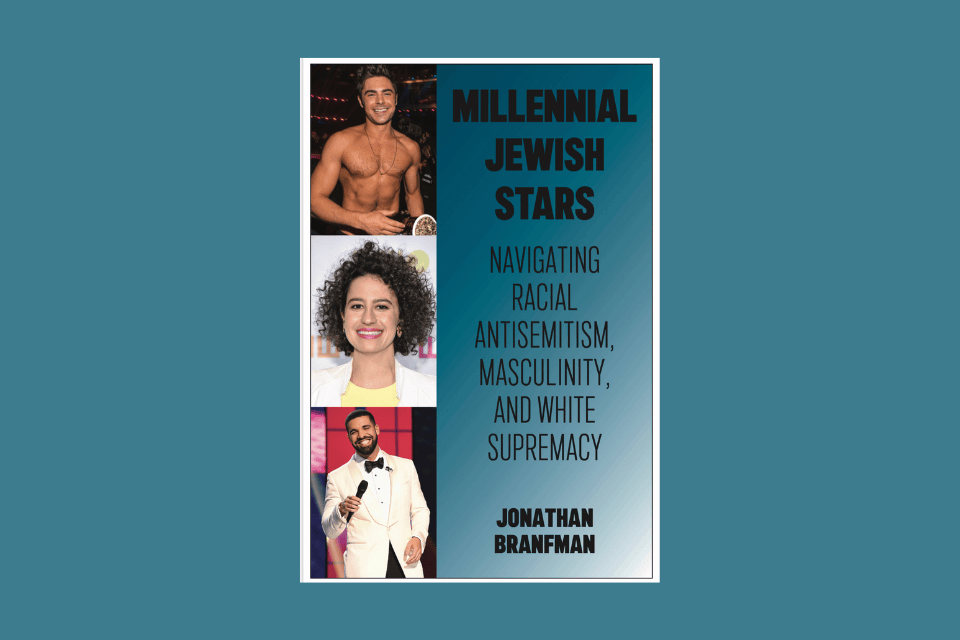

While such representations may seem to concern Jews alone, their impact is far broader. As a scholar of race, gender, and Jewish identity in U.S. media, I find that popular stereotypes about Jews frequently make Jewish performers into symbolic stand-ins for all kinds of hot-button issues that are not directly related to Jewishness. For example, Jewish performers can come to symbolize national debates about everything from class mobility and women’s sexual autonomy to racial appropriation and the future of fatherhood. I explore these dynamics in my book Millennial Jewish Stars: Navigating Racial Antisemitism, Masculinity, and White Supremacy (NYU Press, 2024), which focuses on six performers: the biracial Jewish rap star Drake, comedic rapper “Lil Dicky,” “Jewess” comedians Abbi Jacobson and Ilana Glazer, “man-baby” actor Seth Rogen, and sculpted film star Zac Efron. Each has emerged as a symbolic figure in wider cultural debates.

The notion that these millennial Jewish stars (or indeed, any star) can symbolize much larger political debates draws from star studies, a branch of film theory that analyzes how certain performers come to represent collective hopes, fears, and fantasies.6 For example, John Wayne and Clint Eastwood served within the western film genre to symbolize national hopes and anxieties about white American masculinity in a post-frontier 20th century.7 As these examples suggest, a star’s symbolism often depends on the social connotations of their identity and appearance. For instance, John Wayne’s ability to publicly symbolize American masculinity drew on his image as a tall, straight, white, gentile (non-Jewish) able-bodied man born in the heartland state of Iowa.

Importantly, star studies doesn't suggest that performers always intentionally craft these symbolic meanings, or that audiences consciously decode them. Often, stars simply find that their bodies generate more passionate responses when packaged within specific costumes, hairstyles, characters, and plotlines (such as when John Wayne appeared in cowboy costumes within westerns). And in turn, audiences often find that they simply feel excited, soothed, or captivated by certain stars in certain guises, without consciously noting the ideological subtext that makes these performances so electrifying.

In contrast to Wayne and Eastwood, the millennial Jewish stars that I examine occupy minoritized positions as Jews, women, queer people, and/or people of color. In turn, the specific racial, gendered, and sexual connotations of the stars’ Jewish identities shape their appeal to wider audiences. Take, for example, the comedy duo Abbi Jacobson and Ilana Glazer, creators and stars of Broad City (2014–2019). Their self-described “Jewess” personas earned them effusive love from many young feminist audiences. I argue that their appeal lies in how they update a once-popular “beautiful Jewess” trope, which depicted Jewish women as externally seductive but internally masculinized.8

Although this Jewess trope historically served to stigmatize and fetishize Jewish women, Broad City restyles it to defuse common forms of American antifeminist backlash. Such backlash often stigmatizes disobedient women as repulsively masculinized (supposedly ugly, dirty, hairy, “shrill,” and so on).9 Conversely, Jacobson and Glazer’s rendition of the seductive-yet-masculinized Jewess reassures women that they can remain lovely and lovable (not monstrous) while seizing “masculine” liberties like freely eating, trysting, and roughhousing. And this promise of stigma-free liberation is one reason why Broad City’s leading “Jewesses” inspired particularly ardent, joyful adoration from many women viewers, both Jewish and non-Jewish. In other words, the duo “Jewess’s’” gendered and sexual connotations allow the duo to symbolize a version of women’s future that many women find especially appealing.

Such examples highlight how millennial Jewish stars, like stars of all identities and ages, do more than simply confirm or break stereotypes about their own community. Instead, they provide audiences with tools to imagine new possibilities for their own bodies, identities, and futures. And the emotional force of these tools depends on the specific cultural meanings attached to Jewishness, such as the uniquely seductive-yet-masculinized image of “beautiful Jewesses.” For these reasons, even after America’s news cycle moves on from explicitly discussing antisemitism, everyone who consumes American popular culture has a stake in understanding how popular preconceptions about Jews came to be; how today’s millennial Jewish stars creatively embrace or refashion these tropes; and how these tropes enable Jewish star bodies to carry specific political meanings. In turn, we all have a stake in analyzing how we as viewers consume these star images, using them to make sense of our own bodies, dreams, and lives.

________________________

1 For example, see Jonathan Weisman, “Is Anti-Zionism Always Antisemitic? A Fraught Question for the Moment,” New York Times, December 11, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/10/us/politics/anti-zionism-antisemitism.html.

2 See Liz Essley Whyte, Douglas Belkin, and Sarah Randazzo, “The Little-Known Bureaucrats Tearing Through American Universities,” Wall Street Journal, April 14, 2025, https://www.wsj.com/us-news/education/anti-semitism-task-force-who-247c234e?mod=hp_lead_pos7.

3 David Goodman, “Trump’s Fight Against Antisemitism Has Become Fraught for Many Jews,” New York Times, April 3, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/02/us/jews-trump.html.

4 See Daniel Boyarin, Unheroic Conduct: The Rise of Heterosexuality and the Invention of the Jewish Man (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997); David S. Katz, “Shylock’s Gender: Jewish Male Menstruation in Early Modern England,” The Review of English Studies 50 (1999): 440–62.

5 John Efron, Defenders of the Race: Jewish Doctors and Race Science in Fin-de-Siècle Europe (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994), 99.

6 On stars studies, see Richard Dyer, Stars, New Edition (London: British Film Institute, 1998); Richard Dyer, Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars & Society, 2nd Edition (New York, NY: Routledge, 2004); Chris Holmlund, Impossible Bodies: Femininity & Masculinity at the Movies (New York, NY: Routledge, 2002); Russell Meeuf, Rebellious Bodies: Stardom, Citizenship, and the New Body Politics (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2017); Linda Mizejewski, Pretty/Funny: Women Comedians and Body Politics (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014); Diane Negra, Off-White Hollywood: American Culture and Ethnic Female Stardom (New York, NY: Routledge, 2001); Priscilla Peña Ovalle, Dance and the Hollywood Latina: Race, Sex, and Stardom (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2010).

7 On John Wayne’s political symbolism, see Russell Meeuf, John Wayne’s World: Transnational Masculinity in the Fifties (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2014).

8 On this “beautiful Jewess” trope, see Livia E. Bitton, “The Jewess as a Fictional Sex Symbol,” Bucknell Review 21 (1973): 63–68; Daniel Boyarin, Daniel Itzkovitz, and Ann Pellegrini, “Strange Bedfellows: An Introduction,” in Queer Theory and the Jewish Question, ed. Daniel Boyarin, Daniel Itzkovitz, and Ann Pellegrini (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 1–18; Jonathan Branfman, “‘Plow Him Like a Queen!’: Jewish Female Masculinity, Queer Glamor, and Racial Commentary in Broad City,” Television & New Media 21, no. 1 (2020): 842–60; Ann Pellegrini, “Whiteface Performances: ‘Race,’ Gender, and Jewish Bodies,” in Jews and Other Differences: The New Jewish Cultural Studies, ed. Jonathan Boyarin and Daniel Boyarin (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 108–49.

9 Penny A. Weiss, “‘I’m Not a Feminist, But...,’” in Conversations with Feminism: Political Theory and Practice (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1998), 11–25.

Jonathan Branfman, Ph.D., is a Research Associate at HBI. He worked on his book, Millennial Jewish Stars: Navigating Racial Antisemitism, Masculinity, and White Supremacy (NYU Press, 2024) during his 2020 residency at HBI.